- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The high priest

- Article Subtitle: Harold Bloom’s unworldly notion of literature

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

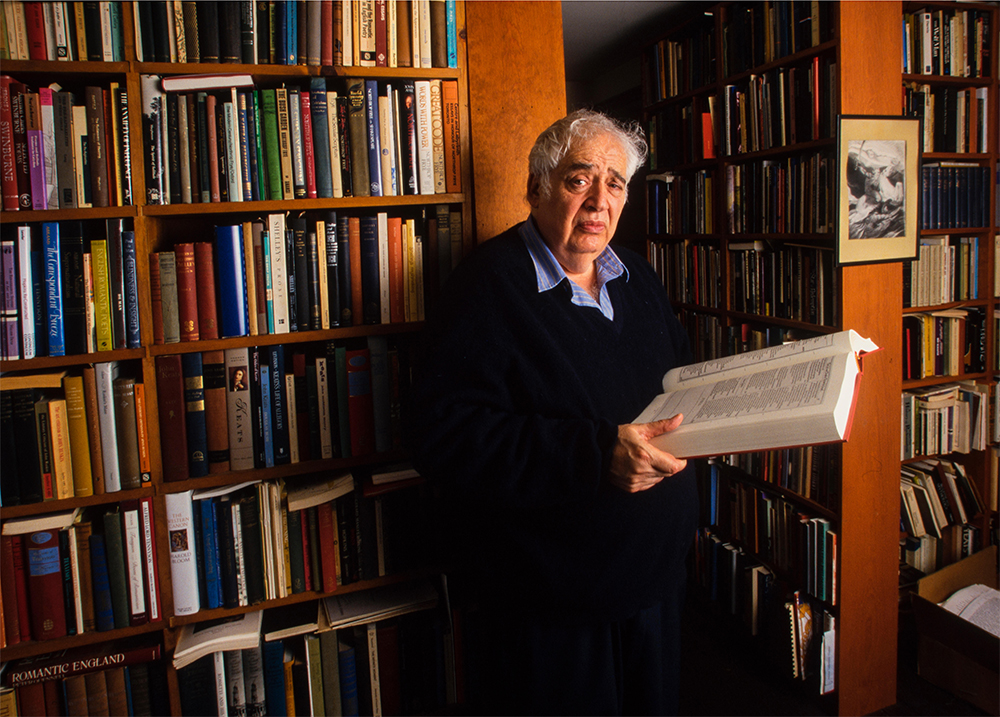

Harold Bloom died in 2019 at the age of eighty-nine. Always prolific, he continued working until the very end. Throughout his final book, he digresses at regular intervals to record the date, note his advanced age, and allude to his failing health. At one point, he reveals that he is dictating from a hospital chair.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Harold Bloom, photographed in New Haven CT (Randy Duchaine/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Harold Bloom, photographed in New Haven CT (Randy Duchaine/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles

- Book 1 Title: Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles

- Book 1 Subtitle: The power of the reader’s mind over a universe of death

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, US$35 hb, 663 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zaNZyO

Alas, Take Arms proves to be a less than impressive finale to Bloom’s long career. The book begins by posing a vexed and potentially very interesting question: ‘In what sense does deep reading augment life?’ Having slogged my way through more than six hundred pages of meandering observations and anecdotes, I now have considerably less life left to augment, yet remain none the wiser. Far from demonstrating the power of the mind over death, Take Arms merely confirms the inevitability of the mind’s capitulation. Bloom published more than his share of potboilers over the years, but his last book is a bloated mess: a series of shapeless chapters searching in vain for a unifying thesis. No man is immortal, but it seems the dying Bloom was not prepared to give up without one last heroic effort to prove himself interminable.

The conceit at the heart of Bloom’s criticism is that literature – or rather the small fraction of literary endeavour he deemed to be of lasting value – arranges itself into a transcendent aesthetic order. Great writers canonise themselves by virtue of their originality, which they achieve via a quasi-Freudian struggle against the potentially smothering influence of powerful literary precursors. There are any number of objections that might be raised against this theory, and Bloom had every one of them thrown at him, but he regarded his obdurate singularity as a point of honour. In Take Arms, he recalls with some pride that William Empson once described his major work The Anxiety of Influence as ‘dotty’, and that his colleague Paul de Man made a point of attending his poetry lectures at Yale because he thought ‘it was wonderful to hear so many new errors in constant creation’.

Many of the paradoxes of Bloom’s thought and all of its absurdity can be traced to his determination to elevate his personal love of poetry to the level of theory. His criticism is the projection of a persona, as much as it is a scholarly exercise. In his later work, he was increasingly open about this. He came to style himself less as a theorist and more as a theologian of literature: the high priest and only admitted member of his own private religion.

In order to arrive at this rarefied position, Bloom was obliged to constrain the potential meaning and purpose of literature in quite drastic ways. He scorned historicism, rejected formal approaches on the grounds that they could not account for the aesthetic splendours or the power of connotation, and dismissed out of hand the notion that literature had any social or political utility whatsoever. That left him, basically, with aestheticism and dubious psychologism, which he spun into a grandiose exercise in escapism, an unworldly conception of literature as an enclosed fantasy camp, where canonical writers were free to ignore tiresome reality and converse exclusively with one another. Bloom all but concedes in Take Arms that this idealised vision of a pantheon of great poets is a personal mythology; he quotes with approval some lines from Wallace Stevens in the context of an argument about the enduring religious truth of the Divine Comedy: ‘The final belief is to believe in a fiction, which you know to be a fiction, there being nothing else. The exquisite truth is to know that it is a fiction and that you believe in it willingly.’

Take Arms pushes these articles of faith to their logical conclusion. Bloom reads his poets in quasi-religious terms as denizens of an expansive universe of the imagination, with Dante at its centre and Shakespeare as its circumference. Yet he also insists that poetry speaks to us as individuals in our solitude. Reading, for Bloom, is an insular and even solipsistic pursuit. It is a way of conversing with ourselves, a form of self-illumination. This is the only worldly effect Bloom will allow. His argument that literature is a purely personal source of consolation tilts his interpretations toward the therapeutic formulas of the self-help movement. ‘The great poems, plays, novels, and stories,’ he maintains, ‘teach us how to go on living, even when submerged under forty fathoms of bother and distress.’ This would no doubt be news to Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, John Berryman, and David Foster Wallace.

Perhaps the most revealing paradox of Bloom’s determined insularity is suggested by the fact that the warmest sections of Take Arms are the elegiac digressions in which he recalls collegial disputes with some of the most prominent literary critics of the last century – F.R. Leavis, Northrop Frye, W.K. Wimsatt, Frank Kermode, Alan Tate, and Geoffrey Hartman among others. These reflections are sometimes waspish but invariably tinged with pathos. That all of these critics, the academic stars of their day, are long dead (and now largely unread) underscores the fact that Bloom himself belongs to a bygone era. More importantly, they identify him as a thoroughly institutionalised creature. For all his singularity, he was the unmistakable product of a particular academic milieu at a particular point in its history.

The intellectual environment and material conditions that allowed Bloom to thrive have changed irrevocably. That he sensed this perhaps accounts for the notable moderation of tone in Take Arms. Bloom certainly does not renounce his old ideas, but he does soften them, just a little. He reduces his most famous theory to affinity, reflecting that ‘the anxiety of influence now seems to me literary love tempered by ambivalence’. In his chapter on Freud, he muses that his ideas have been ‘hopelessly misunderstood’, but that in the long run this does not matter. Elsewhere, he reflects that his jeremiads against the ‘school of resentment’ – his pejorative label for pretty much every theoretical movement of the past fifty years – were a waste of time.

He means they did nothing to halt the advance of the ideas he despised, but for once he is too modest. Bloom’s interventions in the burgeoning culture wars of the 1990s made him arguably the most famous academic critic of his generation, even though he was the most atypical. In positioning himself as the last lonely defender of aesthetic standards, he presented the world beyond the academy with a misleading caricature of the literary critic, his stance merely confirming the unhelpful popular prejudice that aesthetic discrimination is, at best, a monstrous affectation and, at worst, the assertion of an aristocratic view of culture that has no place in a democratic age. In doing so, he actually made it harder to argue that some books really are of enduring cultural value in a way that others are not. It is by no means the least significant part of his legacy that he ended up providing such an overt example of how not to write about literature.

Comments powered by CComment