- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The inconsolable

- Article Subtitle: Truth and illusion in the life of Mike Nichols

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 8 November 2015, a year after his death, a celebration was held for Mike Nichols in the IAC building in New York. The audience included the likes of Anna Wintour, Stephen Sondheim, Tom Stoppard, Steven Spielberg, Oprah Winfrey, and Meryl Streep. Seventy-six years earlier, less than a mile away, seven-year-old Igor Mikhail Peschkowsky walked down the SS Bremen’s gangplank into America and a new life. The transformation of the angry, bewildered immigrant Peschkowski into the outwardly charming, debonair, outrageously talented Nichols is at the heart of Mark Harris’s comprehensive, compulsively entertaining biography.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Mike Nichols

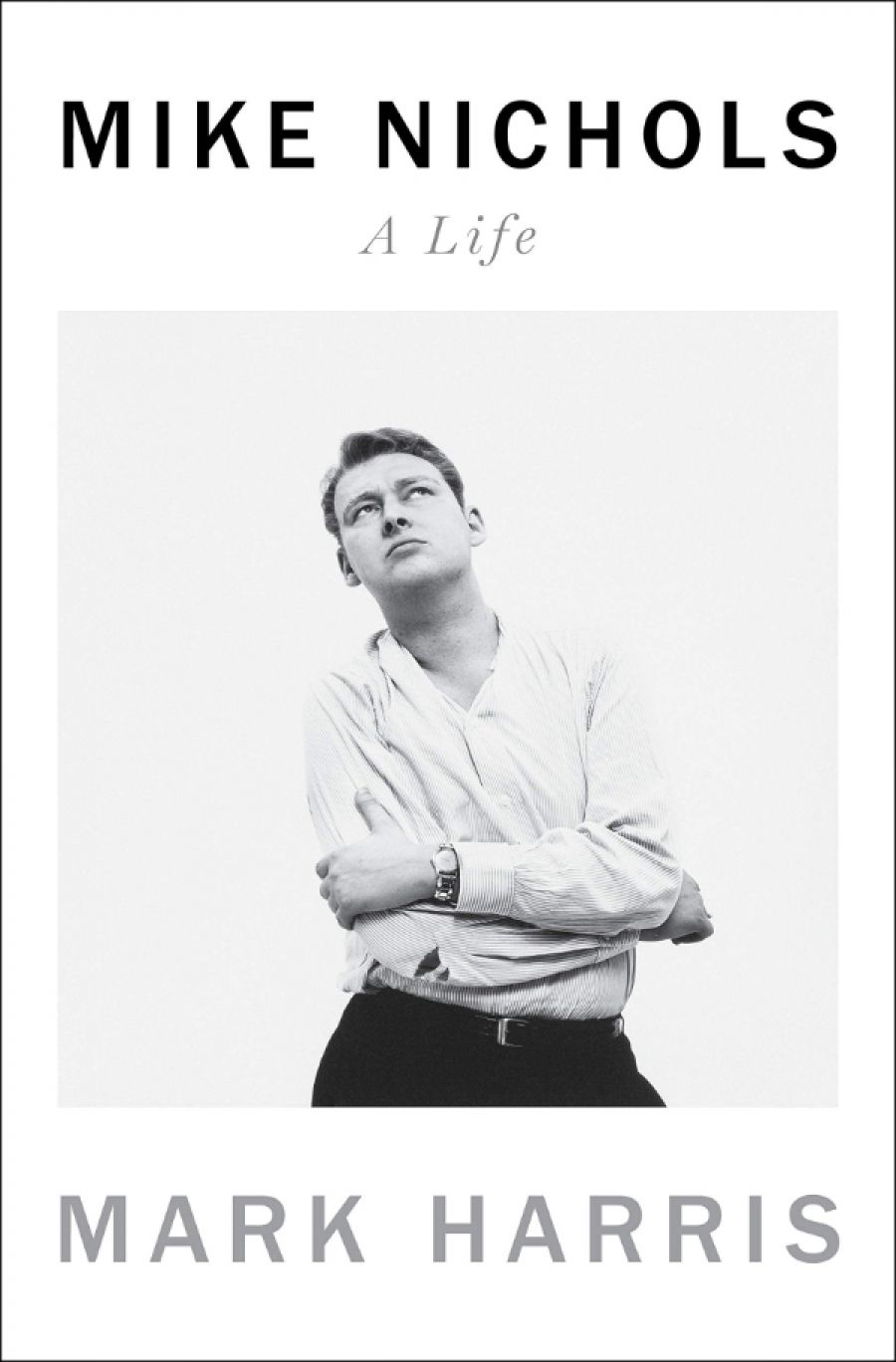

- Book 1 Title: Mike Nichols

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin Press, $52.99 hb, 688 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/P0yJaX

In 1939, as the walls closed in around Germany’s Jewish population, Igor and his brother were dispatched by their ailing mother to join their father, who had established himself under the name Paul Nichols as a doctor in New York. His mother joined them later, but Mike, as he became, for a long time suffered from survivor’s guilt.

To make things more difficult, the boy who was struggling with an unfamiliar country and an unfamiliar language – he claimed that on the ship his only words of English were, ‘I do not speak English. Please do not kiss me’ – had to cope with the fact that a reaction to a whooping cough vaccine had caused acute alopecia. His early schooldays were a nightmare of bullying, which only eased slightly when he managed to persuade his mother to buy him a wig.

Elaine May and Mike Nichols, Golden Theater, 1960 (Everett Collection Inc/Alamy)

Elaine May and Mike Nichols, Golden Theater, 1960 (Everett Collection Inc/Alamy)

The prickly, defensive young man who arrived at the University of Chicago in 1950 found at last some kindred spirits, especially Elaine May, with whom he would develop the improvisational routines that took them to New York and almost instant fame. ‘Pirandello’, one of their most effective sketches, and interestingly one of the few they never recorded, could be seen as the basis for much of Nichols’s later work. It starts with two small children imitating their quarrelling parents. Imperceptibly, the children transform into their parents, who then appear to be replaced by the actual performers having a lethal fight in front of the audience. The quarrel builds to an alarming intensity, at which point the performers turn to the audience and shout ‘Pirandello’. The theme of the warring couple and the playing with truth and illusion are precursors of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which Nichols filmed in 1966, but Nichols’s examination of the destructive tension between the sexes played out again and again in his work, from the films Carnal Knowledge (1971), Heartburn (1986), and Closer (2004) to Harold Pinter’s Betrayal, the last play he directed (2013).

May ended the celebrated partnership in 1961, and Nichols was momentarily at a loss. Leonard Bernstein told him consolingly, ‘Oh, Mikey, you’re so good ... I don’t know at what!’ Nichols, Bernstein, and the world found out soon enough.

When Nichols, in 1963, with no previous directorial experience, was hired to direct Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park, the New York theatre world was sceptical, but from the moment rehearsals began Nichols realised this was ‘the job [he] had been preparing for without knowing it’. He related this to his father’s early death. ‘If you are missing your father as I had all during my adolescence, there’s something about playing the role of a father that is very reassuring. I had a sense of enormous relief and joy that I had found a process that ... allowed me to be my father and the group’s father.’ Nichols’s close relationships with his casts – mentoring them when needed, but giving the more experienced actors room to find their own way – was his great strength as a director. Repeatedly throughout the book, actors talk about the perceptive way he helped them through difficult moments, both in performance and in life.

Having scored big as a neophyte stage director, he proceeded to repeat the feat on film. While watching Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, it’s difficult to believe it is the work of a man who, in preproduction, was not aware of the existence of the zoom lens. He had the temerity to face down the studio head, Jack Warner, who wanted the picture in colour, and to overrule the experienced and supercilious cinematographer, Haskell Wexler, who kept telling him that what he wanted was impossible. Above all, Nichols elicited performances from his four principals that they never surpassed.

With the extraordinary success of his following film, The Graduate (1967), Nichols was now in the top ranks of stage and screen directors: a position he maintained despite occasional disappointments such as Catch-22 (1970) and disasters like What Planet Are You From? (2000).

With amusement and compassion, Harris chronicles Nichols’s flamboyant life style: the several marriages, the glossy apartments, the grandiose estates where he showed off his prize-winning Arabian horses, and the parties, which Nichols called ‘ratfucks’, filled with celebrities. Harris also shows how the insecurity of the outsider still remained and led to the depression that punctuated his career. According to John Lahr, who wrote a profile on him, as the interview was wrapping up Nichols told him: ‘“I’ve really enjoyed this” and I said quite spontaneously “I do well with the inconsolable” and his eyes fluttered – he took a beat – and he said, “We get a lot done, you know.”’

But Harris’s book is not merely a dissection of Nichols’s demons. There is plenty of theatre gossip and backstage intrigue. To paraphrase one of Elaine May’s comments on Mike Nichols’s work, this is a serious look at a major artist that’s as much fun as if it were trash.

Comments powered by CComment