- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dragica and Lotty

- Article Subtitle: Krissy Kneen’s remarkable memoir

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Three Burials of Lotty Kneen begins like a fable, the story of a poor family that wins the lotto and moves to a remote Queensland location to make fairy-tale characters for a tourist attraction called Dragonhall. There should be a happy ending, but there isn’t.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): The Three Burials Of Lotty Keen

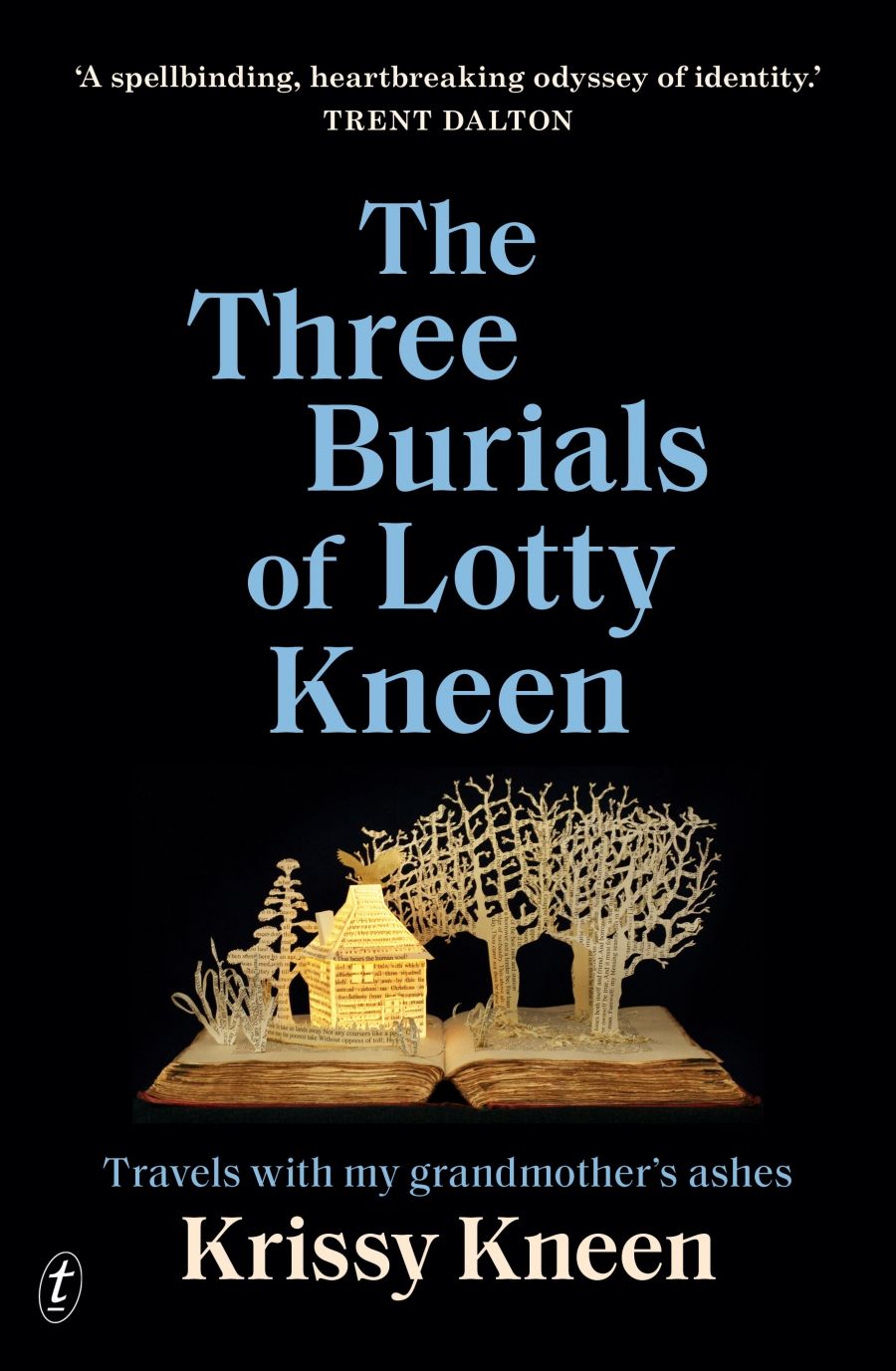

- Book 1 Title: The Three Burials of Lotty Kneen

- Book 1 Subtitle: Travels with my grandmother’s ashes

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $34.99 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2r1nPz

The structure of the book corresponds to Kneen’s travels and the scattering of her grandmother’s ashes in Australia, Slovenia, and Egypt. The narrative meanders from past to present, between what is known and what must be imagined, skilfully interweaving Slovenian folk tales with versions of reality and reiterating anecdotes, obsessions, and anxieties. In a visceral moment reprised from Kneen’s poetry collection Eating My Grandmother: A grief cycle (UQP, 2015), she dips a finger into her grandmother’s ashes and tastes her remains. By literally ingesting the beloved, Kneen acknowledges the genetic and emotional bonds that exist beyond death. Yet it is only after her grandmother’s death that Kneen is free to make the journey forbidden by Lotty.

Lotty was a collector of fairy tales. She kept Kneen’s aunt and mother busy constructing the life-sized papier-mâché dinosaurs commissioned by the Sydney Museum, and her favourite fairy-tale characters for the failed Dragonhall. Her overwhelming desire to protect her daughters and granddaughters from the evils of the world and the treachery of men left them isolated, without friends, with no life outside the home, no volition of their own. Kneen was not allowed to play with other children. Her father was virtually erased after her parents’ divorce, and her grandfather remains a shadowy figure eclipsed by Lotty’s domineering personality.

Krissy Kneen (photography by Anthony Mullins)

Krissy Kneen (photography by Anthony Mullins)

The fable begins to sound more like a horror story. Kneen learns not to ask questions, not to disappoint, but she is disobedient, she wants to know where her family came from; how her grandmother came to be in Alexandria before the 1956 expulsion of foreigners from Egypt. She describes an unpleasant scene: Lotty is caught on film in Kneen’s documentary The Truth About Dragonhall (ABC TV, 2002) boasting spitefully that she would never tell her granddaughter the truth. Kneen is not reticent about blaming Lotty for her issues with body image, obesity, and a lack of self-esteem. What is perhaps more difficult to fathom is the intensity of Kneen’s abiding love for this damaged and damaging woman.

The second and third generation Australian children of survivors of mass catastrophe and dislocation are often inculcated with the belief that their homeland is elsewhere. We grow up with the myth of a better life, but any attempted ‘return’ to places long since destroyed or irrevocably changed is emotionally fraught. With little information to go on, Kneen sets off on a difficult journey in the hope of reconnecting with her heritage and of making sense of her grandmother’s lies and obfuscations. She imagines that Ljubliana will feel like home, but she is disappointed. Though she recognises foods from her childhood and sees traces of her own features in the faces of strangers, the city defeats her. She has no language. The heat, her weight, and poor physical fitness conspire to increase her anxieties.

But it is in Ljubliana that Kneen learns of the Aleksandrinke, women who are the embodiment of ‘poverty, desperation, relocation, dispossession’. In the late nineteenth century and especially after World War I, there was no work for the men of the Slovenian Littoral, but women were offered well-paid jobs in Alexandria. They abandoned their own children to become nursemaids to the children of wealthy expatriates. They sent money back to Slovenia and saved their families from starvation, but their sacrifice was regarded as a source of shame. Many never returned. Kneen thinks that she might have found the reason for Lotty’s silence but, with every scrap of information she gathers, the truth seems to slip from her grasp.

The Three Burials of Lotty Kneen is an extraordinary tale of persistence and of the uncanny series of coincidences that lead to the unravelling of a heart-wrenching family history. It is one of many memoirs in the flourishing genre of travel narratives in search of lost family and an irretrievable past, a quest no doubt prompted by emigration; what John Berger calls ‘the quintessential experience of our time’. But it is also a paean to the enduring power of Lotty Kneen, who survived the vicissitudes of poverty, economic migration, war, loss, and a second transplantation, who remade herself as necessity dictated, and who passed on the gift of storytelling to her granddaughter.

Comments powered by CComment