To celebrate the year’s memorable plays, films, television, music, operas, dance, and exhibitions, we invited a number of arts professionals and critics to nominate their favourites.

Robyn Archer

Zizanie, Meryl Tankard’s new work for Restless Dance Theatre, premièred at the Adelaide Festival: a work of such charm and intelligence it makes you wonder what the word ‘disability’ actually means. The work deserves to be seen Australia-wide.

Back to Back Theatre gave us The Shadow Whose Prey the Hunter Becomes. Typically dangerous, the creator/performers debate the use of the word ‘disability’ and do so in the most minimal theatrical style. Devoid of artifice yet wholly theatrical, this is the most provocative company in the country.

At NGV Australia, Rosslynd Piggott’s survey show I sense you but I cannot see you went from early botanicals, through objects and air of cities, artisan collaborations and vapour paintings. These recent Japan-inspired oils are created with alchemical mastery. There’s an indescribable energy in this ultimate minimalism.

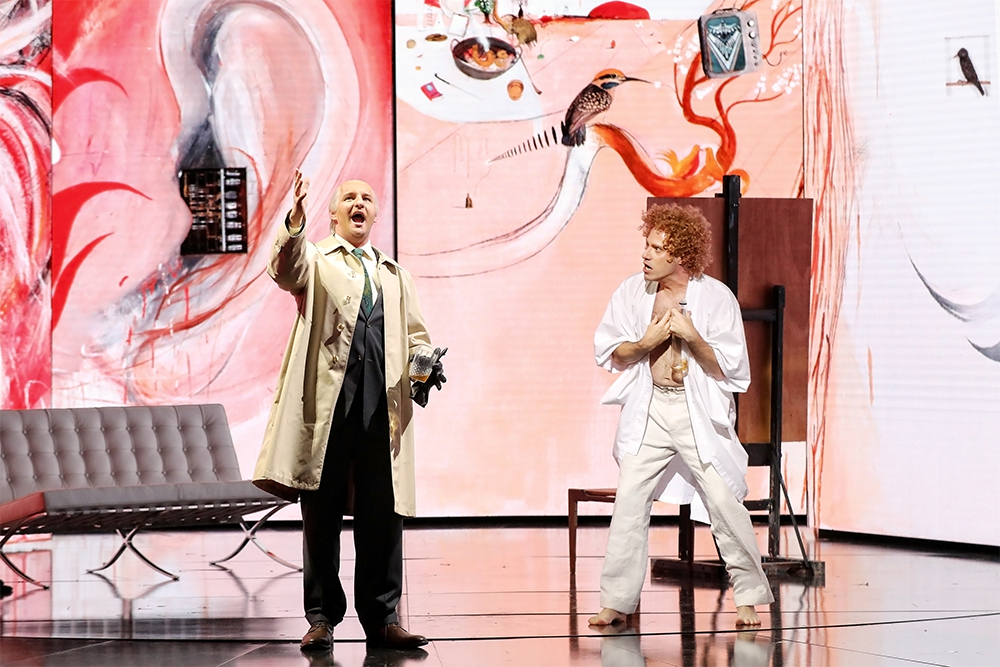

A word on philanthropy. Without Naomi Milgrom’s private collection and assistance we would lack a comprehensive grasp of all that William Kentridge is and does. His Wozzeck was in Sydney, That Which We Do Not Remember graced AGNSW and then AGSA, where we were additionally treated to Adelaide-born, Berlin-resident Jo Dudley’s terrific Guided Tour of the Exhibition: For Soprano with Handbag. Thanks to all inclined to support the arts with such generosity.

Michael Honeyman as Wozzeck in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Wozzeck at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Michael Honeyman as Wozzeck in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Wozzeck at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Felicity Chaplin

This year’s Alliance Française French Film Festival featured a strong program, including new films by Jean-Luc Godard and Claire Denis, and the second feature from Louis Garrel. Charlotte Gainsbourg’s exuberant performance in Eric Barbier’s La Promesse de l’aube was a standout for me, but the real highlight was the darkly comic, metaphysical western The Sisters Brothers (sadly not released since), which screened at the Astor accompanied by a Q&A with director Jacques Audiard. The Astor was the perfect setting for Benoît Debie’s majestic cinematography, and Joaquin Phoenix gives a captivating performance as an unpredictable gun for hire. Audiard said that directing Phoenix was like working with ‘a little devil’. Other highlights of 2019 included Richard Lowenstein’s documentary Mystify for its intimate and absorbing portrait of Michael Hutchence, and Jennifer Kent’s harrowing and atmospheric colonial thriller The Nightingale for the revelation of Baykali Ganambarr in a breakout performance as local Aboriginal tracker Billy.

Baykali Ganambarr as Billy in The Nightingale (photograph via Transmission Films)

Baykali Ganambarr as Billy in The Nightingale (photograph via Transmission Films)

Tim Byrne

It is always fascinating to see the wheel of fortune returning a classic work to the forefront of our consciousness; it tells us as much about our present as our past. This year it was Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge. Directed by Iain Sinclair, this breathtaking MTC production rendered Eddie Carbone’s act of betrayal as a catastrophic rift in the social contract, an act of madness against himself, his community, and his future.

In another return, Melbourne Worker’s Theatre produced an extraordinary polyphony of contemporary voices, primal screams, and competing iterations of our national character with Anthem. Andrew Bovell, Patricia Cornelius, Melissa Reeves, Christos Tsiolkas, and Irine Vela reminded us that agitprop is the beating heart of all theatre, the original call to attention.

Best of all came early in the year. Malthouse brought out Ars Nova’s production of Underground Railroad Game to open their season. It was one of the most accomplished, provocative, and thoughtful works in years. Reaching deep into the history of slavery and oppression in the United States, it threw an uncompromising light on our own racial inadequacies. The past is always present.

Zoe Terakes in A View from the Bridge (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Zoe Terakes in A View from the Bridge (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Gabriella Coslovich

Two of the most profoundly moving works I saw this year brought me face to face with a past that, as author Bruce Pascoe has shown, is well documented but that white Australia largely chooses to ignore. Indigenous soprano–composer Deborah Cheetham transformed the requiem – a mass for the dead, traditionally sung in Latin – into a work of bold contemporary relevance, recasting it in the language of the Gunditjmara people to honour the fallen on both sides of the resistance wars on Victoria’s south-west coast. With its passages of terror, grief, and beauty, Eumerella, a War Requiem for Peace unified non-Indigenous and Indigenous choirs with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and rightly won a prolonged standing ovation at its single performance at Hamer Hall.

Tasmanian Aboriginal artist Julie Gough’s exhibition Tense Past, presented by the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and Dark Mofo, was born of an equally deep enquiry into the impact of colonisation. Gough’s outdoor installation Missing or Dead, at Dark Path in Hobart, was the most perturbing element. In the heaviness of a Hobart mid-winter night, I was confronted by a dimly lit, nightmarish expanse of trees upon which were hung or nailed posters of 180 Tasmanian Aboriginal children lost or stolen during the early years of the colony.

Deborah Cheetham performing in Eumeralla: A war requiem for peace with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (photograph by Laura Manariti)

Deborah Cheetham performing in Eumeralla: A war requiem for peace with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (photograph by Laura Manariti)

Humphrey Bower

My theatre highlight in 2019 was the Belvoir/ Co-Curious co-production of S. Shakthidharan and Eamon Flack’s sprawling Sri Lankan-Australian saga Counting and Cracking at the Adelaide Festival. Two outstanding location- or community-based works in Perth were 5 Short Blasts by Madeleine Flynn and Tim Humphrey (in a small boat on the upper reaches of the Swan River and Fremantle Harbour) and The Lion Never Sleeps by Noemie Huttner-Koros (a walking tour of queer Northbridge and its history before, during, and after the AIDS crisis). Joel Bray’s intimate confessional/participatory dance theatre work Biladurang (in a hotel room on the forty-fourth floor of the Sofitel on Collins in Melbourne’s CBD) and Daddy (Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall) both explored Aboriginality and queerness in a way that was playful, tender, confronting, and inclusive. My favourite piece of new writing was See You Next Tuesday, Perth playwright Samantha Nerida’s delirious monologue in three voices about teenage female sexuality, adventure, and danger, intelligently directed by Alexa Taylor at The Blue Room Theatre. Finally, the most spectacular international show I saw was Dimitris Papaioannou’s darkly humorous work of corporeal theatre, The Great Tamer, at the Perth Festival.

Vaishnavi Suryaprakash and Sukania Venugopal in Counting and Cracking (photograph by Brett Boardman)

Vaishnavi Suryaprakash and Sukania Venugopal in Counting and Cracking (photograph by Brett Boardman)

Michael Shmith

It takes bravado for an opera company to bring neglected works into the repertoire. The year was bookended by two such productions. In February, Victorian Opera brought to the cavernous Palais Theatre, in St Kilda, the first fully staged Melbourne production of Parsifal (1882). Conducted by the company’s artistic director, Richard Mills, and directed by Roger Hodgman, this was a sterling effort that went to the heart of Wagner’s Bühnenweihfestspiel.

In October, from IOpera, came the Australian première of Ernst Krenek’s jazz-inspired opera, Jonny spielt auf (1927). Conducted by Peter Tregear – a real labour of love and scholarship – this one-off concert performance was a vivid reminder of what was once the most popular opera in the world.

A quick mention of galvanising performances by the MSO and its departing chief conductor, Andrew Davis, of a Stravinsky double bill: Perséphone and Le sacre du printemps.

Andrew Davis conducts The Rite of Spring as part of the MSO's Stravinsky Double Bill (photograph by Laura Manariti)

Andrew Davis conducts The Rite of Spring as part of the MSO's Stravinsky Double Bill (photograph by Laura Manariti)

Des Cowley

The Stonnington Jazz Festival delivered a week of outstanding performances, including the Australian première of Peter Knight’s composition The Plains, based on the Gerald Murnane novel. Elsewhere, jazz and film came together in a memorable concert by the Adam Simmons Creative Music Ensemble devoted to the music of the late Polish jazz composer Krzysztof Komeda, best known for his scores for filmmaker Roman Polanski. Miles Okazaki’s brilliant and unorthodox interpretations of the music of Thelonious Monk, as arranged for solo guitar, was a personal highlight at this year’s Melbourne International Jazz Festival. But nothing could surpass the masterful performance by the Art Ensemble of Chicago as part of Melbourne’s Supersense Festival. Celebrating their fiftieth year, the augmented Ensemble, led by the unflagging seventy-nine-year-old Roscoe Mitchell, one of the AEC’s two remaining original members, unleashed a 100-minute single piece flow of music that ran the gamut from classical to African rhythms, swing and free jazz.

Herbie Hancock at the 2019 Melbourne International Jazz Festival (photography by Anna Madden)

Herbie Hancock at the 2019 Melbourne International Jazz Festival (photography by Anna Madden)

Susan Lever

In July, Meyne Wyatt brought his first play City of Gold to the Griffin Theatre. This witty, confronting performance reminded us how little life has changed for those on the margins while we city dwellers live in comfort. Most of the audience left speechless with awe and shame.

In a complete contrast, Whiteley celebrated that comfortable middle-class life. With its melodic score by Elena Kats-Chernin and massive screens showing some of Whiteleys more colourful and optimistic paintings, it offered art as pure pleasure, with any darkness deftly smoothed over. I left thinking the real genius on display was Kats-Chernin.

The same week, the Sydney Chamber Opera staged another new Australian opera, Pierce Wilcox and Elliott Gyger’s adaptation of Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda. While Gyger’s music became a little monotonous, Wilcox’s libretto turned a prolix novel into a pithily philosophical drama, brilliantly acted and sung by the young cast.

Bradley Cooper as Frank Lloyd and Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Bradley Cooper as Frank Lloyd and Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Peter Rose

The Adelaide Festival brought many highlights. One performance (sadly not repeated elsewhere) that shook me to the core was the 600-year-old a cappella Sretensky Monastery Choir, with its six virtuosic soloists and its phenomenal sonorities and surges. Monsieur Crescendo himself (Rossini) would have been on his feet at the end, as we all were.

The Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s concert version of Peter Grimes reminded us what remarkable metaphysical angst Britten depicts in his first opera. What is home? Where is home? Stuart Skelton, in the title role, offered an acute study in exhaustion, social estrangement, and defeat. Nicole Car, making her role début, was a radiant Ellen Orford.

Opera Australia and David McVicar’s luminous production of Così fan tutte finally came to Melbourne and convinced some of us that it might just be Mozart’s finest opera. In an exceptional cast, Jane Ede and Anna Dowsley stood out as the equivocating sisters.

Bravo to Red Stitch for giving us Caryl Churchill’s hilarious, unnerving satire Escaped Alone. Julie Forsyth was magnetic, her closing monologue (‘Terrible rage’) quite unforgettable.

Julie Forsyth in Escaped Alone (photograph by Jodie Hutchinson)

Julie Forsyth in Escaped Alone (photograph by Jodie Hutchinson)

Alison Stieven-Taylor

My first review for ABR was David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948–2018, an expansive collection of works by one of South Africa’s most insightful photographers. This exemplary expression of the documentary form was followed by Ballenesque, Roger Ballen: A Retrospective. Bizarre, thrilling, and at times repellent, Ballen’s work is at the other end of the photographic spectrum to Goldblatt, but both artists challenge conceptions of humanity, politics, and power. Hoda Afshar’s breathtaking Remain features portraits of asylum seekers on Manus Island. Shot in secret in a makeshift studio, Afshar’s work is unequivocally political, portraying the beauty in suffering. Dina Goldstein’s satirical series Gods of Suburbia brilliantly questions religious faith in the era of technology. Oded Wagenstein’s Like Last Year’s Snow, a lyrical dissertation on ageing, moved me to tears. Both featured in Head On Photo Festival (Sydney). And my final highlight: Civilization: The Way We Live Now. Exhilarating and apocalyptic, this is the show of the summer.

Eyesight testing at the Vosloosrus Eye Clinic of the Boksburg Lions Club. 1980 silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Eyesight testing at the Vosloosrus Eye Clinic of the Boksburg Lions Club. 1980 silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

Will Yeoman

Recorded music aside, I’ve spent a lot of time this year listening to WASO, especially when principal conductor Asher Fisch was in town. His ability to galvanise the orchestra in performance, while continuing to shape and refine its technical and artistic qualities, is a constant source of wonder, especially when orchestra and conductor share the platform with superb international artists. Three of this year’s WASO concerts stand out for me. An Evening with Gun-Brit Barkmin – Beethoven, Wagner, Richard Strauss – showcased not only the interpretative range of this fine German soprano but Fisch’s considerable fluency in German operatic repertoire. To hear Fisch conducting Danish violinist and conductor Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider in a superlative performance of Elgar’s Violin Concerto, followed by Szeps-Znaider conducting Fisch in Schumann’s Piano Concerto – well, that took things to a whole new level.

Gun-Brit Barkmin (photograph via West Australian Symphony Orchestra)

Gun-Brit Barkmin (photograph via West Australian Symphony Orchestra)

Gillian Wells

Spartacus is a Bolshoi Ballet specialty. Aram Khachaturian’s romantic score is lyrical and lush, and Yuri Grigorovich’s ambitious choreography captures the plight of the gladiatorial slaves and the phalanxes and testudos of Roman military tactics. In the recent Bolshoi production presented by The Queensland Performing Arts Centre, the superbly synchronised military sequences made an ideal foil for the breathtaking airborne artistry of Igor Tsvirko in the leading role.

In Concert Seven of this year’s Bangalow Music Festival, the Orava Quartet’s performance of Wojciech Kilar’s rarely heard Orawa thrilled the crowd. The Quartet’s crystal-clear, lovingly precise vibrancy was like a portal through which the sights, sounds, and colours of a Polish rural scene were indelibly revealed.

The Tyalgum Music Festival presented a stunning performance of Strauss’s Four Last Songs by soprano Greta Bradman and the Tinalley String Quartet in the festival’s Friday Gala. Another highlight was an airing of Schubert’s Fantasie in F minor. This work for four hands is a treasure, though in the hands of the unimaginative it can be witheringly repetitive. The Viney-Grinberg Piano Duo’s superb interpretation breathed with such fresh insight, drama, and edge-of-the-seat silences that every repetition was a joy.

Kevin Jackson and Robyn Hendricks in Spartacus (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Kevin Jackson and Robyn Hendricks in Spartacus (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Ben Brooker

Sometimes there is so much bad theatre around you’re left wondering what you ever saw in the medium in the first place. And yet, when the reminders come, as they always do, the effect can be incendiary. Three performance works qualified in the past twelve months: Counting and Cracking, S. Shakthidharan’s astonishing epic (and début play!) about four generations of one Sri Lankan family; SHIT/LOVE, fortyfivedownstairs’s double bill of equally brilliant one-act plays by Patricia Cornelius, high poetess of Australia’s underclass; and The Second Woman, Nat Randall and Anna Breckon’s marathon work for stage and video. Across a single scene repeated one hundred times over twenty-four hours, it excavated contemporary gender roles in an utterly compelling fashion.

Nat Randall and collaborators, The Second Woman (2017), at Carriageworks (photograph by Heidrun Löhr)

Nat Randall and collaborators, The Second Woman (2017), at Carriageworks (photograph by Heidrun Löhr)

Barney Zwartz

Melburnians, as always, had a rich choice of operas from several companies. Opera Australia, unsurprisingly, led the way with a brilliant co-production of Rossini’s Il Viaggio a Reims, composed for the 1824 coronation of Charles X, lost for 150 years and given here in its Australian première. The other OA highlight was a concert performance of Andrea Chénier, with superstar soloists in Jonas Kaufmann and Eva-Maria Westbroek. Baritone Ludovic Tézier almost stole the show.

Victorian Opera’s best was an outstanding Parsifal, again with a fine cast led by Burkhard Fritz, Peter Rose, and Katarina Dalayman, with the luxury of Teddy Tahu Rhodes as Titurel. Perhaps the most interesting was tiny IOpera’s witty and inventive concert performance in the Australian première of Ernst Krenek’s 1927 sensation Jonny spielt auf. Twice before planned and dropped by bigger companies, the opera made it thanks to the passion of Krenek specialist Peter Tregear, who conducted masterfully.

Sian Sharp as Marchesa Melibea and Shanul Sharma as Conte di Libenskof in Il Viaggio a Reims (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Sian Sharp as Marchesa Melibea and Shanul Sharma as Conte di Libenskof in Il Viaggio a Reims (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Richard Leathem

ACMI may have closed its doors for much of 2019, for redevelopment, but not before it screened the ultimate movie montage. Christian Marclay’s twenty-four-hour opus The Clock (2010) delivered a masterclass in film editing. The Clock features clips from thousands of films made since the creation of cinema; each scene contains a time corresponding with the actual time. Suspense builds without ever being released. Cinema has been described as the art of time; Marclay’s addictive installation took the practice of time manipulation to the ultimate degree.

Cinema of a more traditional length reached its acme, as ever, at the Melbourne International Film Festival. This year the Georgian-set And Then We Danced showed how beautiful art can come from harsh reality. Levan Akin’s response to seeing members of the LGBTIQ community in his home country being violently attacked was a rapturous celebration of self-expression in defiance of oppressive traditions.

Giorgi Tsereteli as David and Levan Gelbakhiani as Merab in And Then We Danced (photograph via Cannes Film Festival)

Giorgi Tsereteli as David and Levan Gelbakhiani as Merab in And Then We Danced (photograph via Cannes Film Festival)

Sophie Knezic

The year featured three outstanding exhibitions by established artists in full command of their medium. The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, curated by Shihoko Iida and Melissa Keys at Buxton Contemporary, offered a rare opportunity to see a cluster of Gojak’s materially poetic and literally incisive works surprisingly well-paired with Koganezawa’s exuberant drawings and animations.

Composite Acts by David Rosetzky – a one-night-only exhibition as part of the Channels Festival – showed him excelling in the role of artistic director. Featuring a video of dancers Shelley Lasica, Arabella Frahn-Starkie, and Harrison Ritchie-Jones choreographed by Jo Lloyd (two of them performed on the night), with ludic sculptures by Sean Meilak and a poignant score by composer Duane Morrison, this seamless work deftly balanced the live and the recorded, whose overlappings became an affective metaphor for the probing of memory and reflection.

A survey exhibition of one of our most interesting artists working with digital animation, Arlo Mountford: Deep Revolt (Shepparton Art Museum) highlighted the tautness of Mountford’s work, its mash-up of art history, manga, and genre film exposing our entanglements in the mediatised world.

Arlo Mountford, The Triumph, 2010 video still single channel video installation, 16:9 HD, stereo. Duration 9:11 min. Image courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery Melbourne

Arlo Mountford, The Triumph, 2010 video still single channel video installation, 16:9 HD, stereo. Duration 9:11 min. Image courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery Melbourne

Patrick McCaughey

Richard Serra has taken over Gagosian’s prime spaces in NYC this fall. The huge, multi-piece Forged Rounds at West 24th St sets the key: ‘Weight is a value for me … I have more to say about the balancing of weight, the diminishing of weight … the disorientation of weight, the disequilibrium of weight …’ The drawings, Diptychs and Triptychs, at the mother house on Madison Avenue exemplified the theme, and the 99’ length of Reverse Curve added dynamism.

I admired Kristin Headlam’s illuminations of Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s long poem The Universe Looks Down at the Baillieu Library in Melbourne. Although the poem has brilliance and liveliness on the page, it is not an easy work. Headlam’s spirited responses – a bestiary of the poem – drew my attention to overlooked passages. I returned to The Universe Looks Down imaginatively refreshed with a new awareness and admiration.

Richard Serra, Nine, 2019 (photograph via Gagosian)

Richard Serra, Nine, 2019 (photograph via Gagosian)

Francesca Sasnaitis

The musicians’ joyous engagement with one another and with the audience was the highlight of Silkroad Ensemble’s performance in Perth. Opening with an impassioned dialogue between Cristina Pato’s gaita (Galician bagpipes) and Wu Tong’s suona (Chinese horn), and travelling through Brazilian, Vietnamese, Indian, and Sephardic traditions, and the compositions of György Ligeti, Antonín Dvořák, and John Zorn, the exhilarating program was truly representative of founder Yo-Yo Ma’s ideal of cultural exchange and collaboration.

The survey exhibition Tom Nicholson: Public Meeting at ACCA, in Melbourne, proffered a spectacular argument in favour of socially driven arts practice that combines arresting visuals, profound thought, and an ongoing conversation with community. Nicholson’s deployment of text as both graphic element and narrative vehicle in projects, such as Towards a monument to Batman’s Treaty (2013–19) and After action for another library (1999–2001/2019), multiplied and challenged readings of contested colonial histories with surprising emotional intensity.

Cristina Pato and Wu Tong from the Silkroad Ensemble (photograph via the Perth Festival)

Cristina Pato and Wu Tong from the Silkroad Ensemble (photograph via the Perth Festival)

Ian Dickson

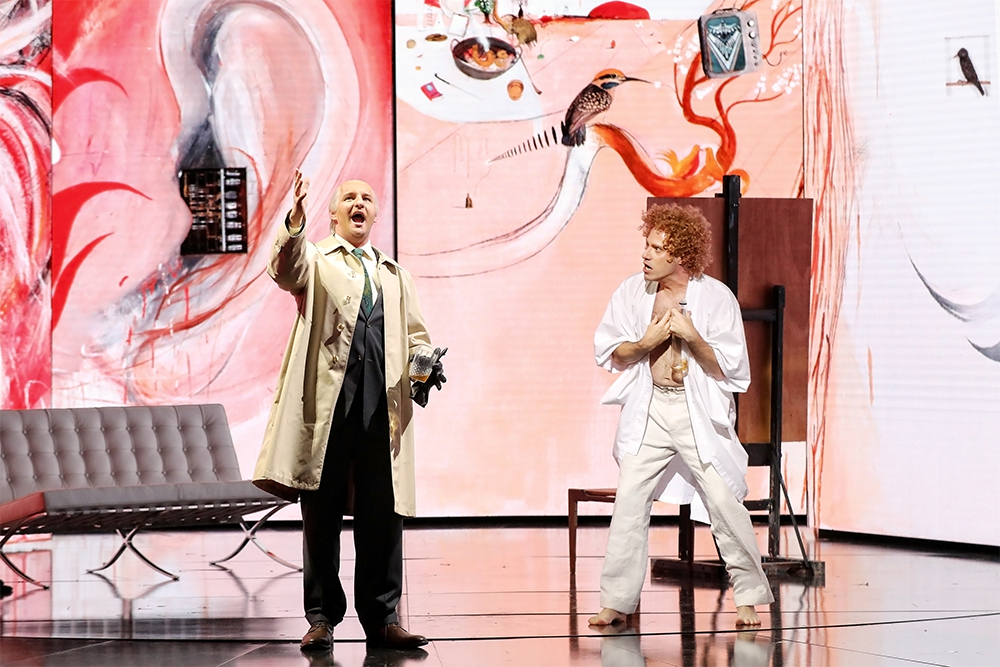

It is fitting that in a year in which the concept of masculinity has been put firmly in the spotlight and populist movements have sought to demonise ‘the other’, three undoubted highlights concerned themselves with flawed men, outsiders who are brought down by their otherness. In his searing production of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck for Opera Australia, William Kentridge’s familiar charcoal drawings summoned up a hellish World War I nightmare. As the increasingly isolated and paranoid Wozzeck, Michael Honeyman gave a career-defining performance.

Isolated, paranoid, pitiful, and brutal are all adjectives that could also apply to Peter Grimes, the eponymous protagonist of Benjamin Britten’s opera, which was given a magnificent semi-staged performance at the Sydney Opera House. David Robertson led a superbly in-form SSO, and the Sydney Philharmonia Choirs rose to the occasion brilliantly. Their stentorian cries of ‘Peter Grimes’ nearly blew Utzon’s sails into the Harbour. But it was the superlative cast that set the seal on this incomparable evening. Can there be any doubt that Stuart Skelton is the reigning Grimes of the moment? He has all the power of Jon Vickers but also a tenderness that the great Canadian lacked in this role. It says much for the rest of the cast, especially Nicole Car and the American baritone Alan Held, that they were all performing at his level.

The story of the third outsider, John Grant, the schoolteacher in Kenneth Cook’s Wake in Fright, was given a brilliantly radical retelling at the Malthouse. Director Declan Greene worked seamlessly with the extraordinary Zahra Newman, who played all the characters and provided a devastating introduction. The staging of the two-up game and the roo shoot were bravura moments of theatre.

Zahra Newman in Wake in Fright (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Zahra Newman in Wake in Fright (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Kim Williams

Three things standout in particular for me in the 2019 year – all epic in vision and realisation.

Counting and Cracking from Belvoir St Theatre (Sydney Festival and Adelaide Festival). A huge, valiant production written by S. Shakthidharan in a collaboration with director Eamon Flack, who realised an indelibly memorable production about four generations of Sri Lankans moving between Sydney and Sri Lanka in a beautiful and tragic epic. It was cast with a large, entirely non-Anglo Celtic troupe that delivered gripping storytelling.

The new film from Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, Never Look Away, is even better than his last (The Lives of Others, 2006). Loosely based on the German artist Gerhard Richter, this sweeping piece of cinematic storytelling is almost perfect in terms of realisation, and devastating in impact. It addresses the artistic sensibility, mid-twentieth-century politics, humanity, and, above all, love.

Meryl Tankard’s restaging of her remarkable work Two Feet for the Adelaide Festival, with the twenty-first century’s greatest ballerina, Natalia Osipova, in a solo role that portrayed the tragic, tempestuous life of the twentieth-century heroine Olga Spessivtseva, provided a wondrous chamber work with devastating impact.

Natalia Osipov in Meryl Tankard's Two Feet (photograph by Regis Lansac)

Natalia Osipov in Meryl Tankard's Two Feet (photograph by Regis Lansac)

Tali Lavi

Watching The Australian Dream on opening night in a near-vacant suburban cinema rendered the devastation twofold. The documentary examines the state of this country’s heart, made rotten by racism and the disavowal of Indigenous Australia’s centrality to the national narrative. Adam Goodes and Stan Grant stand as beacons of dignity.

Sometimes artists are so ingenious that their works induce a heightened state of wonder. Bryony Kimmings’s I’m a Phoenix, Bitch (Arts Centre Melbourne) was a melange of puppetry, subversive song, encounter with the woods of Grimm, and multimedia, as Kimmings revealed her experiences of post-natal depression and having a sick child.

Honourable mentions: THE RABBLE’s feverish production of Alison Croggon’s poetry-infused My Dearworthy Darling and Nakkiah Lui’s Black Is The New White (STC/Melbourne Festival), where racial and sexual politics were subversively and outrageously skewered amid audience dancing and joyfulness.

Jennifer Vuletic in My Dearworthy Darling (photograph by David Paterson)

Jennifer Vuletic in My Dearworthy Darling (photograph by David Paterson)

Michael Halliwell

This has been a good year for offerings from Opera Australia, but two stand out, for different reasons. Wozzeck (a co-production with the Salzburg Festival), directed by artist William Kentridge, dazzled as a visual feast with a kaleidoscopic array of images punctuating Berg’s bleak look at struggling humanity. Of similar impact, Strauss’s Salome was distinguished by the outstanding performance of the title role by American soprano Lise Lindstrom. Salome is an almost impossible role, visually and vocally, but Lindstrom’s lithe and alluring physical presence and steely tone were as close to perfection as is possible.

Revisiting a well-loved play for the first time in nearly forty years has its perils. Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Tom Stoppard’s quasi-autobiographical, meta-theatrical meditation on love and betrayal, The Real Thing, paid homage to the play’s 1980s social, and particularly musical, context, but made it a searingly contemporary experience.

Lise Lindstrom as Salome in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Salome at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Lise Lindstrom as Salome in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Salome at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)