- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As the ship carrying nine-year-old Cleary Sullivan and his mother, Cate, sets sail from Liverpool, there is a ‘flurry’ among the passengers. A ‘violent slash of red; tall as a house and shining wet’ has appeared on the dock, visible only to those onboard. Cleary’s mind fills with images of ‘some diabolical creature of the deep, blood erupting from its mouth’. The reality is more prosaic – some spilt paint – but it is an ominous beginning.

Like Meg Mundell’s début, Black Glass (2011), The Trespassers takes place in an unforgiving near-future. Cleary is one of more than three hundred masked passengers escaping a pandemic-riven United Kingdom. Their passage to Australia has been arranged through the ‘Balanced Industries Migration’ scheme, indentured servitude in all but name. The old-fashioned mode of transport and technological restrictions imposed on the passengers, combined with sailors casually shooting down drones, and terms like ‘shippers’, ‘sanning’, and ‘the stream’, give the novel an almost timeless quality, though its concerns are very much of the moment.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

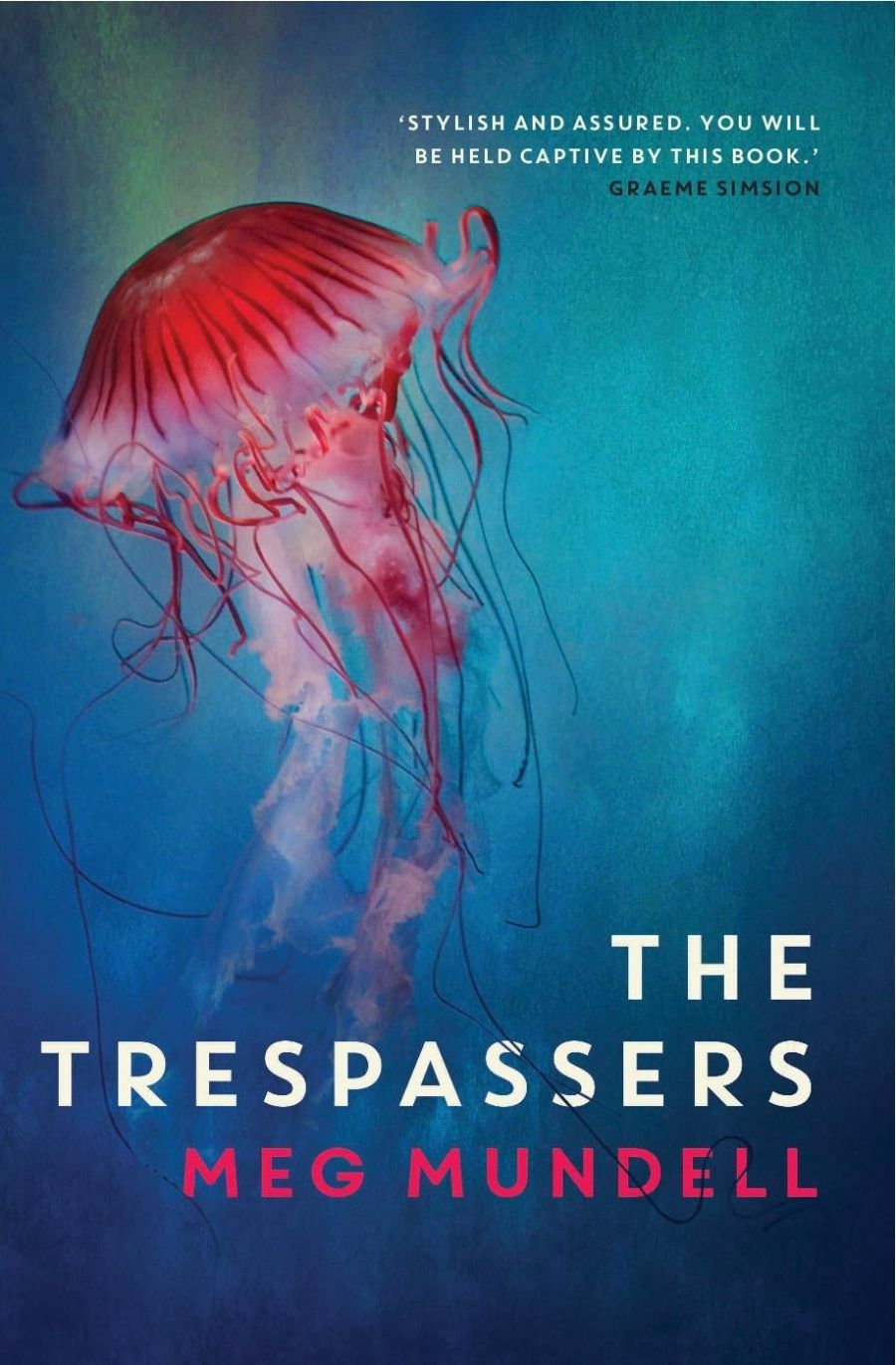

- Book 1 Title: The Trespassers

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.95 pb, 278 pp, 9780702262555

The Trespassers is told through three idiosyncratic voices: Cleary, watchful, Irish, ‘small for his age’, survivor of an almost fatal ‘super-flu’ that left him only able to hear ‘shadow-noise, remote and muffled, like an afterthought’; intense Glaswegian singer Billie, traumatised by her experiences in the ‘death wards’ and plotting to escape the BIM system and make her fortune entertaining miners and executives on the fringes of Australia’s ‘Third Boom’; and Tom, an anxious young Englishman working as a teacher after his family fortune dissolved in ‘the crashes’. His is the only narrative presented in the first person; it reveals a weakness for pills, maritime puns, and a handsome Scottish seaman. All three hope that what awaits them in Australia will make their time in this ‘floating rabbit warren’ worth it.

After the ship makes its way like a dystopian icebreaker through the ‘floating debris, clearing a temporary trail that vanished as the rubbish reconverged’, the passengers are finally free to remove their medical masks. For Cleary, mostly reliant on lip-reading and makeshift sign language to communicate, this is momentous as it ‘return[s] language to the faces around him’. However, it’s not long before a sailor is found murdered. Sickness leaves the crew and passengers of the under-equipped Steadfast struggling to survive and to uncover the truth.

There are several resonances with the New Zealand-born Mundell’s previous works. The name Steadfast was used in an earlier short story (‘Narcosis’, commended in the 2011 Jolley Prize and published in her 2013 collection, Things I Did for Money). However, the novel shares more than just the name of a ship with Mundell’s other works. Informed concern for the vulnerable and marginalised infuses The Trespassers. (Mundell is a former Big Issue deputy editor and the editor of We Are Here [2019], an anthology by writers who have experienced homelessness.) Other preoccupations recur, such as the importance of home and belonging, the value and perils of investigative reporting in an era of clickbait and online comments, the bonds of friendship and family, and an endearing interest in birds. Mundell also explores the ways in which social hierarchies can assert themselves and then break down under pressure. She writes perceptively about isolation and exile and their relationship to survival and tribalism, the importance of hope, the contagious nature of fear, and the galvanic force of anger. As one character notes: ‘Anger is a dangerous emotion, so the experts say: too often misdirected, to easily turned inward. But surely there are times when it’s the only just and right response.’

Meg Mundell (photograph by Amanda Soogun)

Meg Mundell (photograph by Amanda Soogun)

The Trespassers is intelligent, provocative fiction that uses unsettling echoes of historical and contemporary events to conjure a depressingly plausible future. Margaret Atwood has noted there is nothing in her seminal novel The Handmaid’s Tale that ‘human beings had not already done somewhere at some time’. The Trespassers offers a similarly disturbing ring of authenticity, drawing as it does on history and current events. These include the typhus-plagued ship the Ticonderoga, quarantined outside Melbourne at Point Nepean in 1852; the migration of ‘Ten Pound Poms’ following World War II; and more recent governmental responses to refugees and those seeking asylum.

The impact of the looming climate crisis isn’t highlighted as directly here as in other recent speculative fiction, but it is evident in the floating bottles that are ‘like a layer of scum on soup’, the ‘abandoned beachfront homes’ left ‘half submerged’, the casual asides about toxic spills, and the references to ‘fatal floods in California, food riots in India’.

Mundell deploys new technologies and folk superstitions to great effect, and subtly weaves in allusions to Greek mythology, including a brief but devastating nod to the Stygian ferryman Charon. Her writing is richly textured and atmospheric, and her characterisation is nuanced. There are villains here, but Mundell is careful to show complexity in individuals and flickers of humanity and compassion in groups. It is easy to see why this unflinching novel has been optioned for television.

The narrative trajectory of The Trespassers has a certain relentless inevitability, but there are some genuinely shocking moments. Fortunately, there are also some flashes of hope and humour amid the sickness, menace, oppression, and death. As one character flippantly remarks to an insincere external medic, ‘They promised us pina coladas … I’m thinking of suing.’

Comments powered by CComment