- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Claude Monet lived in Argenteuil in the 1870s, he famously worked in a studio-boat on the Seine. He painted the river, he painted bridges over the river, he painted snow, the sky, his children and his wife, and, famously, a field of red poppies with a large country house in the background. Argenteuil is to Paris roughly what Heidelberg and Templestowe are to Melbourne. Once a riparian haven for plein air painters interested in capturing the transient optics of natural phenomena, it is now a suburban interface with a diminishing habitat for anything but humans.

Actually, Heidelberg and Templestowe are in good shape when compared to Monet’s old river haunt. When he was living in Argenteuil, the population was fewer than 10,000 people, most of whom were asparagus farmers, vintners, fishermen, and craftspeople. Now the suburb is home to more than 100,000, many of whom are commuters making the train trip into Paris every day to work. The only shimmering light of interest would probably come from their phones.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

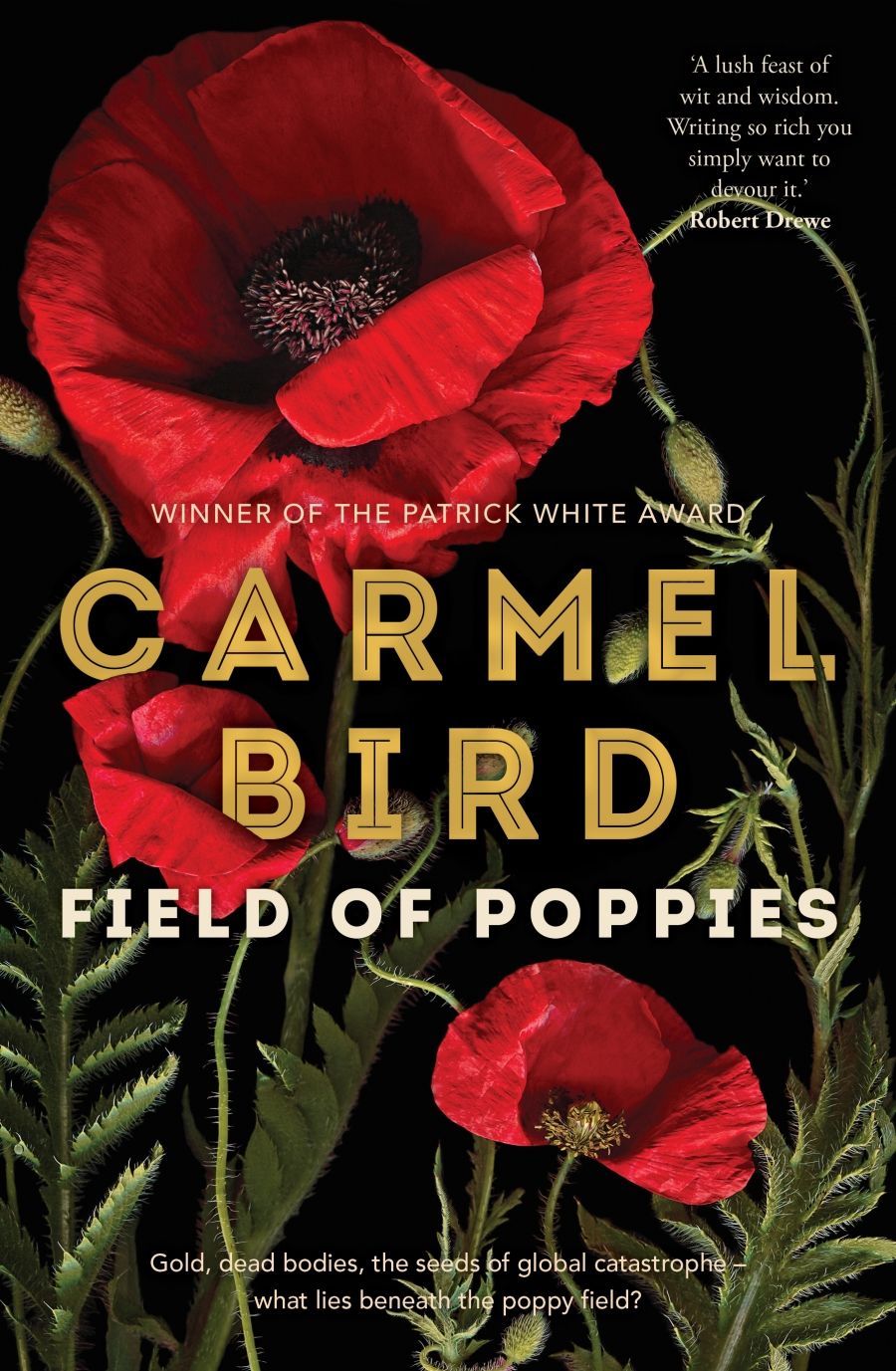

- Book 1 Title: Field of Poppies

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.99 hb, 241 pp, 9781925760392

Where once a stream was a noun denoting a house of fish, now it is a verb describing digital product. We stream music, we stream audiobooks, movies, and news. In Carmel Bird’s new novel, Field of Poppies, the chatty narrator, Marsali Swift, likes to plonk down in front of her Chromecast television to enjoy the sequence of random images constantly displayed in the absence of the stream. ‘I like this,’ she says. ‘It’s mesmerising and weirdly diverting.’ One day she sees her favourite painting, Monet’s Poppy Field Near Argenteuil float across the screen, and her reverie is broken by its intense familiarity. ‘No line of exclamation marks, no treasury of powerful words could convey my astonishment and thrill,’ she writes.

It turns out that for Marsali it is a copy of Monet’s painting, rather than the original painting itself, that has sparked her obsession. When Marsali was a child, her great-aunt Clarissa, who used to set up her easel not on a boat on the Seine but among the fruit trees of her Yarra bank garden in old Hawthorn, painted beautifully faithful copies of European masterworks. Clarissa’s version of Monet’s Poppy Fields near Argenteuil had ever since held Marsali under her spell. So much so that it became a dream image she would actively pursue in her own adult life. Pulling up sticks in Melbourne, Marsali and her erudite doctor husband, William, move to a fictional central Victorian town called Muckleton. They buy a historic property called Listowel where, yes, Marsali can have her own field of poppies and her own grand house looking over it.

Muckleton is a gentrified hotspot of post-urban ‘bobos’ (bourgeois bohemians) and sceptical locals. Marsali immerses herself in the variously entitled pursuits that a bobo might in such a place. She joins a book group, goes to local recitals, laments the empathy deficit of Western civilisation, and appoints her rustic property with the eclectic accoutrements of a middle-class fantasia.

Of course, it was never going to work, and the unravelling of precisely how it goes awry is the tale the novel unfolds. But this is a tree-change story told in an unusually pithy manner. Like the Chromecast stream or the teeming internet, Bird’s novel is structured in bricolage, patched together from scrolling sequence of character studies, anecdotes, opinions, facts, and recollections that both fillet and bolster what is essentially a crime plot with the feel of Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries.

Carmel Bird (photograph via HarperCollins)

Carmel Bird (photograph via HarperCollins)

This is a book of unpretentious, free-ranging confidence, by a novelist for whom the written page is an entirely natural habitat. Bird builds her narration via a disarmingly vivacious and, at times, even frivolous voice, only to lay down some key tragedies of the culture in which we live. In this assemblage, nearly all woke issues are touched on, as she describes the mismatch of Marsali’s rural fantasy with the utilitarian realities of Muckleton, and, ultimately, her and William’s eventual return to an apartment on the forty-second floor of Melbourne’s own slice of hairy-chested architectural kitsch, the Eureka Tower.

On the way the Listowel house gets robbed, a violinist named Alice is murdered, the book group ransacks Lewis Carroll as if for clues, a gold mine called Red Opium Poppy is kickstarted by a Chinese consortium, Aboriginal massacres are eulogised, roadkill statistics are analysed, and the history of red poppies, from Monet through to their militarisation via the pathos of Flanders Field, is discussed. The novel is an collection of digressive fascinations both light and dark, knitted together with a focused tone of irony, wisdom, and joy.

In this sense, Field of Poppies is a deceptively emblematic book by a mature and unzipped writer. It disarms the more typical literary expectations of pacing and plot in favour of the faulty happenstance to which we are daily prone. Not Monet but a copy of Monet. Not a copy of Monet but its simulation on an automated screen. In Carmel Bird’s hands, our increasingly hackneyed dystopia is a both a darkly revisioned wonderland and a touchscreen of self-reflexive humour. Like Barbara Pym or Elizabeth Taylor, she doesn’t plumb the depths, but the point is that you know she’s been down there. What she brings to the surface is variegated and alive. There’s no point meekly surrendering to the absurd levels of commodified gloom after all. In the end, you do have to laugh.

Comments powered by CComment