- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Finance

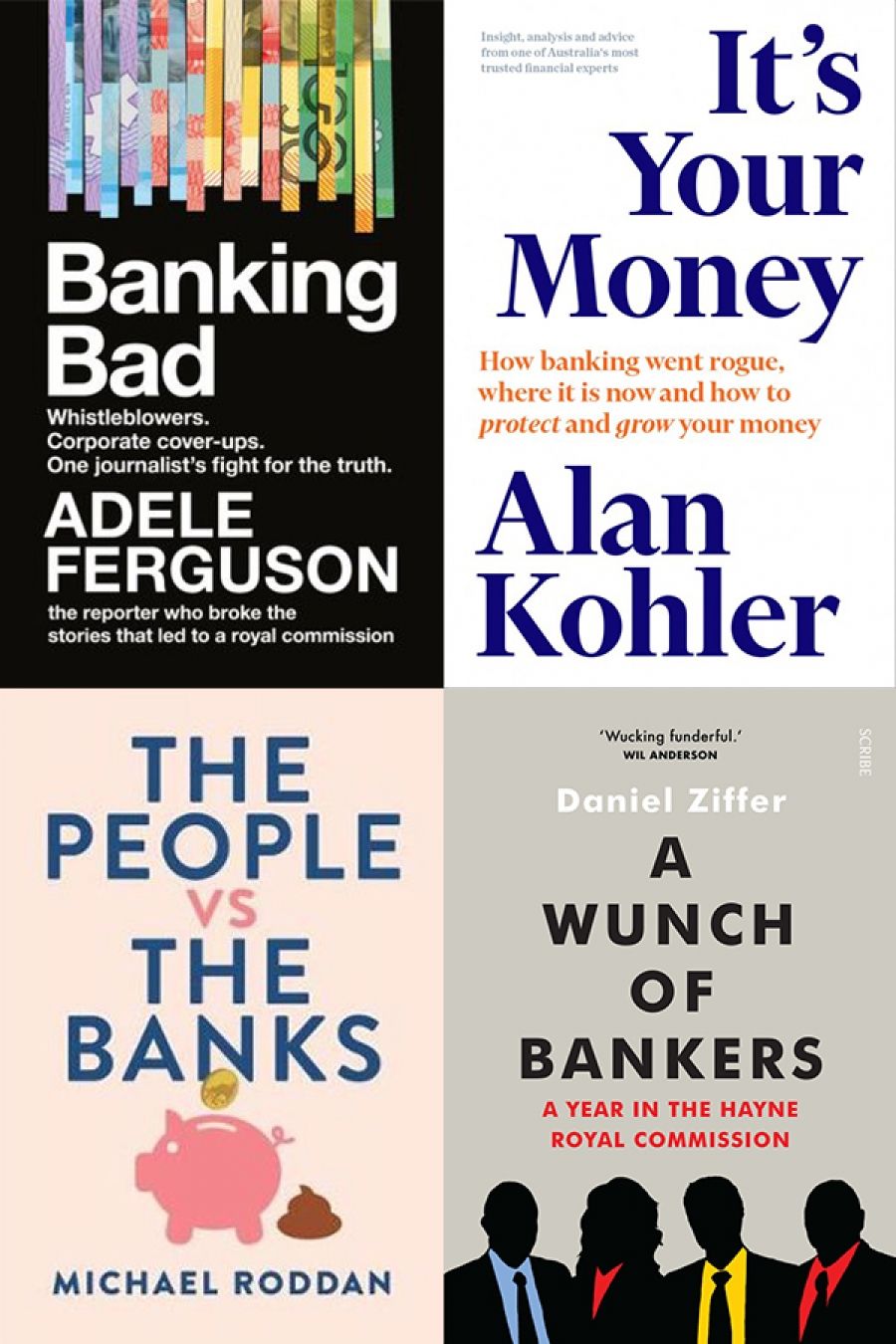

- Custom Article Title: The Money Power: Four books on the big banks

- Review Article: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Bank bashing is an old sport in Australia, older than Federation. In 1910, when Labor became the first party to form a majority government in the new Commonwealth Parliament, they took the Money Power – banks, insurers, financiers – as their arch nemesis. With memories of the 1890s crisis of banking collapses, great strikes, and class conflict still raw, the following year the Fisher government established the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, ‘The People’s Bank’, as a state-owned trading bank offering cheap loans and government-guaranteed deposits to provide stiff competition to the greedy commercial banks gouging its customers.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

Hayne’s year-long Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry – completed in February 2019 – has made public a decade of fraud, forgery, and criminality in Australia’s financial sector that has cost thousands of people their livelihood and well-being. Fees charged to customers receiving no service, even to the accounts of the dead. Insurance, mortgages, and credit cards aggressively sold to the vulnerable and those unable to afford it. Drought-stricken farmers hit with hefty penalties for defaulting on their loans. Billions sucked out of retirement savings in fees by bank-run super funds. All this, and more, as the banks recorded annual profits of $5 to $10 billion. CBA’s centrality in these scandals, thirty years after privatisation, speaks volumes about the rot that has set in.

Royal Commissions are often cynically dismissed as stalling devices of government. Despite some high-profile sackings and pending class actions, this may ultimately prove true of this inquiry, too. Yet the Hayne Royal Commission captured the imagination. From the government’s initial politicking against the inquiry – Scott Morrison called it populist hubris, John Howard ‘rank socialism’ – through to a desperately grinning Josh Frydenberg receiving the final report from a frowning, handshake-refusing Hayne, it was national theatre. Public enmity fed not only on the harrowing revelations, but a national mood darkened by wage stagnation, growing inequality, and ever-deepening distrust of once-venerated institutions. Several journalists who helped convey this Zeitgeist have now penned longer reflections that attempt to make sense of the banks’ descent.

Banking Bad by Adele Ferguson

Banking Bad by Adele Ferguson

ABC Books, $34.99 pb, 405 pp, 97807333340116

Where to begin this story? The Royal Commission’s terms of reference limited the inquiry to misconduct since 2008. Yet, as Adele Ferguson makes clear in Banking Bad, to assume bad banking has resulted from complacency that set in after the GFC, or from the handiwork of a few ‘bad apples’ – two narratives bankers liked to pedal through the Royal Commission – is to suffer a convenient bout of amnesia.

Ferguson rightly begins her account much earlier, with the deregulatory shifts enacted by the Hawke government in the early 1980s. The Australian dollar was floated, capital controls abolished, and banking licences opened to foreign firms. The imperatives that motivated these changes, including persistent stagflation and the global dismantling of the Bretton Woods system, are not mentioned, but Ferguson does provide sufficient context for understanding a dramatic alteration in banking practice.

Financial deregulation enhanced prosperity by making credit more accessible and helped Australia withstand global shocks. It came at a cost. From the mid-1980s, Australian banks sought novel methods to build market share, selling controversial foreign-currency loans that carried lower repayment rates but exposed borrowers to international currency fluctuations. Sold a dream, many farmers and business were ruined. Aggressive business lending helped induce the 1990–91 recession, which resulted in the privatisation of CBA and the implementation of the Four Pillars policy in the 1990s, prohibiting CBA, ANZ, NAB, and Westpac from merging. These policies were intended to secure competition. They created four financial behemoths.

Through the 1990s, the big four swallowed up smaller competitors, innovated new financial products, which they sold through US-styled marketing tactics, and placed commission-based advisers in their branches. Staff were set sales targets that were dutifully enforced by executives whose remuneration packages were tied to increasing shareholder value. A CBA manager at Goulburn, for example, was told to sell 150 loans a week, in a community with only 10,000 income-earning adults. The banks then embarked on strategies of vertical integration, acquiring wealth-management firms and expanding into insurance and the newly created superannuation scheme, completing what Ferguson describes as the banks’ rapid transmogrification ‘from service providers to sellers of products’. The Money Power attained unprecedented reach and influence.

Ferguson has built a stellar career exposing the consequences of these transformations. Much of Banking Bad recounts scandals covered by Ferguson since the late-2000s. She revisits the fraudulent behaviour of CBA financial adviser ‘Dodgy’ Don Nguyen, the antagonist of her award-winning 2014 Four Corners story, who was rewarded with extraordinary sums for pushing products and risky portfolios on to unknowing clients. She also recalls the complacent practices of ANZ-backed Timbercorp that cost modest investors millions, the NAB’s predatory lending to customers that could never repay, as well as CBA’s horrendous treatment of life-insurance clients, using outdated medical definitions to deny cancer patients their claims.

Ferguson’s reportage revealed that seemingly isolated incidents stemmed from structural practices. Each exposé encouraged more whistleblowers and victims to come forward. In alliance with Nationals Senator John ‘Wacka’ Williams – himself a farming victim of the foreign-currency loans scandal – momentum built towards a Royal Commission. Ferguson compassionately shares victim’s stories, including not just the loss of homes and farms but relationship breakdowns and suicide. She lauds courageous whistleblowers, many of whom were subjected to smear campaigns by their former employers.

The grudging announcement of a Royal Commission in November 2017 marked a triumph for Ferguson, the whistleblowers, and the victims. However, in outlining the inquiry’s proceedings through the book’s second half, Ferguson repeatedly expresses disappointment at the range of topics the Commission either hurried through or entirely overlooked. Granted a year, the Commissioner chose to examine only twenty-seven ‘representative’ case studies from thousands of submissions of wrongdoing.

The People vs The Banks by Michael Roddan

The People vs The Banks by Michael Roddan

Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 352 pp, 9780522875188Michael Roddan’s The People vs the Banks traverses much of the same terrain, addressing the Royal Commission and its back stories thematically rather than chronologically. This approach enables Roddan, a journalist with The Australian, to disentangle the political and corporate subplots that fed into the Royal Commission. He unpacks with skill and clarity how banks and financial-service providers systematically exploited agribusiness, superannuation, and Indigenous peoples in remote communities.

Roddan’s best chapters are those that step back from the Royal Commission and examine how bad banking has impacted the Australian economy more generally, especially the housing market. He shows how banks have preyed upon the RBA’s decade of rate cuts, which successive governments have relied upon to stimulate economic growth against a dwindling mining boom. Lowering rates has also triggered near-identical declines in the interest paid on deposits and government bonds. Egged on by lucrative tax arrangements, investors seeking higher yields (many for retirement) have been increasingly pushed into property investment. As the Royal Commission highlighted, those doing the pushing have been ‘independent’ financial advisers and mortgage brokers paid trailing commissions by the banks to sell their loan products, especially notorious interest-only loans. By 2016, reports Roddan, one in every two mortgage approvals was for a landlord. Housing prices have ballooned under such conditions, as lax lending and over-leveraged investors pumped up one of the riskiest housing bubbles in the world, locking out of the market a generation of first homebuyers in the process.

All this makes for sombre reading. Yet at times the Commission played out like a dark comedy, as a parade of executives bumbled and deadpanned their way through questionings. Ferguson likened the performance of Jack Regan, head of finance at AMP, to a Monty Python sketch. Unable to explain why he had issued an ‘unreserved’ apology on behalf of his firm, he had to be walked through the twenty-one times his department had blatantly lied to ASIC.

A Wunch of Bankers: A year in the Hayne Royal Commission by Daniel Ziffer

A Wunch of Bankers: A year in the Hayne Royal Commission by Daniel Ziffer

Scribe, $32.99 pb, 362 pp, 9781925849363It is such absurdity that Daniel Ziffer repeatedly captures in his aptly titled A Wunch of Bankers: A year in the Hayne Royal Commission. In a rollicking and witty blow-by-blow account of his year covering the Hayne Royal Commission for the ABC, Ziffer attends to the more grotesque malpractices unearthed by the Royal Commission. ‘Introducer’ commissions, for example, were paid to solicitors, accountants, and property developers for referring customers to the NAB for mortgages that totalled $24 billion over three years, a practice that festered with bribery, fraud, and unconscionable loans.

Drawing heavily on hearing transcripts, Ziffer delights in replaying the squirming, verbal contortions of witnesses under the inscrutable questioning of Hayne and the counsels assisting. Ziffer’s most poignant moments come in his dissection of the meeting minutes, emails, and memos tabled to the Royal Commission, which clinically detailed executives’ knowledge of misconduct and their decisions not to act to protect shareholder value. When the CBA considered abolishing broker commissions in 2017, recognising the benefits to customers, it quickly abandoned the idea fearing ‘first-mover disadvantage’ if other banks did not follow. ‘These were processes,’ writes Ziffer, ‘focused on getting a sale at all costs.’

It’s Your Money: How banking went rogue, where it is now and how to protect and grow your money by Alan Kohler

It’s Your Money: How banking went rogue, where it is now and how to protect and grow your money by Alan Kohler

Nero, $34.99 pb, 289 pp, 9871760641016Such revelations have prompted renowned business commentator Alan Kohler to offer lucid advice on how to negotiate the finance industry in It’s Your Money: How banking went rogue, where it is now and how to protect and grow your money. Kohler offers an eminently readable account of where the banks went wrong in a swift fifty-page summary – much of it mirroring Ferguson’s story – before decoding financial jargon and processes for the honest punter. Not for the first time, he cautions special care with superannuation, regretting Paul Keating’s initial failure to properly regulate the system.

These books differ in their conclusions as well as emphases. Where Roddan is relatively lenient on the regulators, ASIC and APRA, absolving their shortcomings for a lack of resources, Ferguson, like Hayne, finds no excuse for their ‘cosy’ relationship with banks, the mediations behind closed doors, and instances of co-drafting media releases.

There are disagreements over Hayne’s report, too. When he announced the Royal Commission, Malcolm Turnbull declared that ‘it will not put capitalism on trial’. Accordingly, Hayne’s seventy-six recommendations were mostly about conserving the banking system through subtle changes aimed at reforming culture. Roddan agrees with Hayne’s assessment that any sudden, wholesale rearranging of the financial sector might destabilise the economy. According to Ferguson and Kohler, however, Hayne should have tackled vertical integration, forcing the separation of product selling from advice giving. Such laws were a common feature in Western economies before the 1980s and have again featured prominently in the US and UK reforms since the GFC. This approach has had less traction in Australia. Some banks have themselves partially abandoned the strategy since the Royal Commission, selling off their wealth management arms. But they are free to return to it.

Roddan describes his book as a ‘first draft of history’, a fitting epigraph for the others, too. Writing in a hurry but with purpose, and enlivened by their journalists’ contacts, Ferguson, Roddan, and Ziffer eschew organising concepts such as neoliberalism and globalisation, which are now routinely deployed to explain these fractured times. (Kohler frames the deregulating 1980s in terms of an economic rationalism inspired by Milton Friedman.) Rather, as Hayne also concluded, they explain this history as one of raw, institutionalised greed. The bad actions of advisers, brokers, tellers, and call centres were rewarded with handsome commissions. These actions were endorsed by executives because they inflated the banks’ share price and thus their huge remuneration packages. Such remuneration was accepted by major shareholders because it seemed to drive up their returns.

There are, however, global and conceptual challenges that need to be explored. As Ferguson notes, what has occurred in Australia extends an international pattern. Banks the world over have been shamed – if not failed – on account of poor practices that can be traced back to the reforming 1980s. Such circumstances should raise more fundamental questions about how banks can be made to better serve society. Roddan recalls Ben Chifley’s remarkable attempt to nationalise the banking system and Menzies’ civic ideal of home ownership. While Ziffer finds these old ideas venerated among banking victims, they are not presented in these books as viable policy options but as historical curiosities. If scrutinising banks – bank bashing – has not waned, perhaps the accompanying appetite for the institutional experimentation of yesteryear has.

Nonetheless, these books force us to think hard about the role banks play in our everyday lives, an omnipresent power we allow to be almost invisibly exercised. For Roddan, this means challenging our unthinking ‘Dollarmite to death’ monogamy with banks. For Kohler, self-education is key. Yet Ferguson and Ziffer fear that politicians have learned little and sense this moment of introspection may already be slipping away. Memories are short and consequences are soon forgotten. The Morrison government has already declined to enforce Hayne’s most significant recommendation to outlaw mortgage-broker commissions. Ferguson is doubly pessimistic given that whistleblowers – the chief weapon against bad banking over the past decade – are now pursued by authorities in new, frightening ways.

In this light, these books are essential, urgent reading. They remind us of the integral role fearless journalism plays in maintaining open societies. They remind us that banking is too important to be left to the Money Power.

Comments powered by CComment