- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

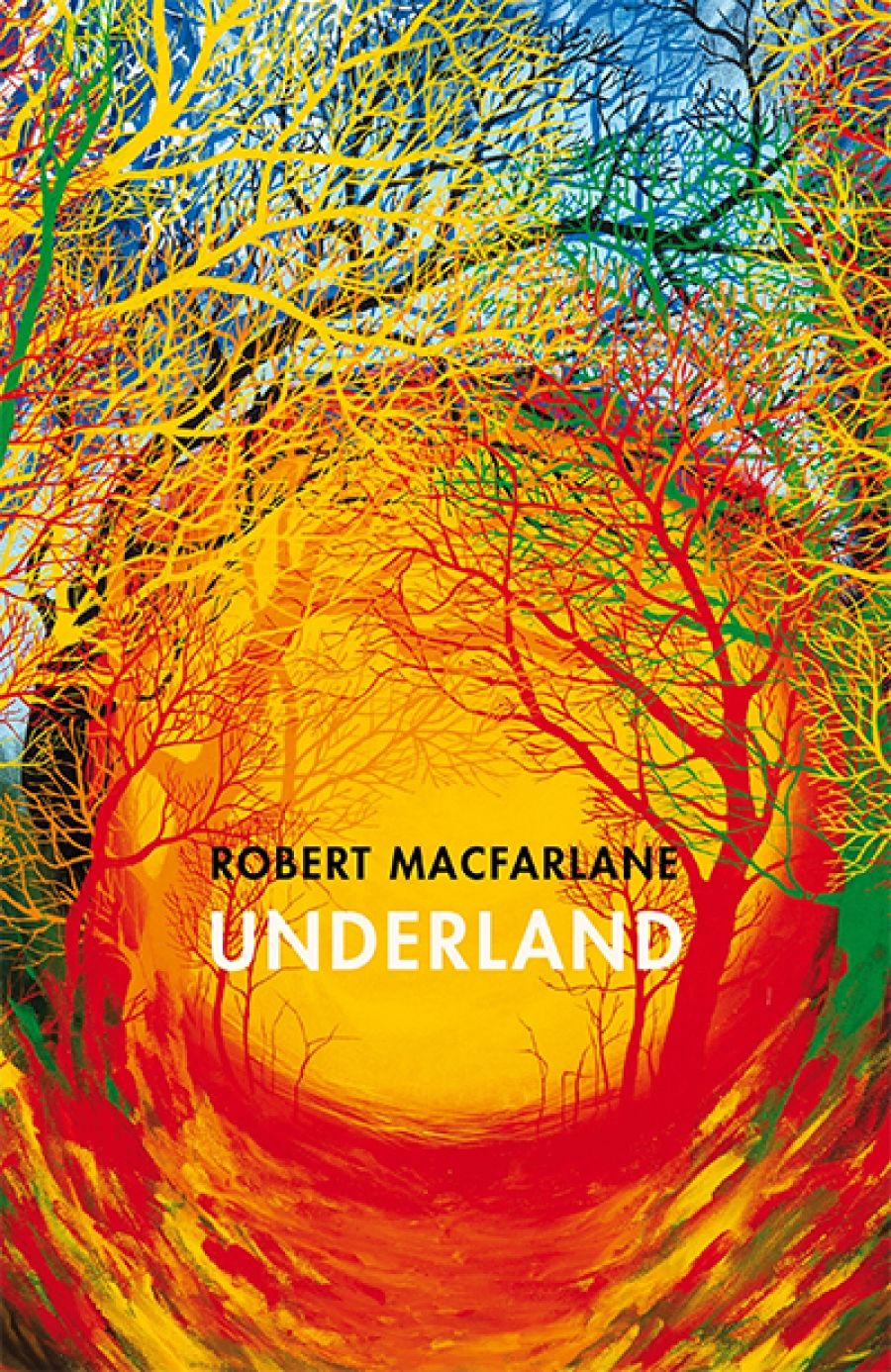

- Book 1 Title: Underland

- Book 1 Subtitle: A deep time journey

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $45 hb, 496 pp, 9780241143803

My copies of Macfarlane’s books are all heavily annotated. There are many gems to revisit. His luminous prose and affinity for etymology reveal unexpected associations. ‘To understand,’ he explains, is ‘to reveal by excavation’, ‘to descend and bring to the light’. Macfarlane’s craving for not just topographic extremes but linguistic ones steers the reader through a lexicon of arcane terms – eldritch, reliquary, ruckle, plastiglomerate. He salvages old words and pops tangy new ones in our mouths. Keep your dictionary close at hand. Landmarks (2015) and The Lost Words (2017; illustrated by Jackie Morris) showcase Macfarlane’s lexical longings, but all his books attest to his profound love of language. Extreme environments demand an extreme and exacting lingo. Macfarlane absorbs it from his caving comrades: ‘The language of extreme caving is often openly mortal and tacitly mythic: stretches of passageway “dead out”, one reaches “terminal sumps” and “chokes”, the furthest-down regions are known as “the dead zone”.’

Macfarlane also ponders how language shapes perceptions of place: ‘An aversion to the underland is buried in language … height is celebrated but depth is despised … we are disinclined to recognise the underland’s presence in our lives, or to admit its disturbing forms to our imaginations.’ Yet his trawl through classical literature reveals ‘something seemingly paradoxical: that darkness might be a medium of vision, and that descent may be a movement towards revelation rather than deprivation’. In the final chapter, he asks how we might communicate the threat of buried nuclear waste to ‘unknown beings-to-be across chasms of time’. This question spawned the field of nuclear semiotics, accentuating the onerous challenges of communication across indeterminate timeframes.

Macfarlane is an astute observer and a powerful writer. His words create visual impressions more evocative than those he provides pictorially. Rarely does one read such captivating accounts of rock as in his description of karst in ‘Starless Rivers’, guiding the reader through a ‘fabulously complex and imperfectly understood’ labyrinthine landscape. Books about the subterrain are inevitably about rock. However, it is the interface of soil surface–subsurface where Macfarlane becomes aware of the symbiotic mycorrhizal tapestry uniting fungi and plants, the ‘intricacy of interrelations’ often dubbed ‘the wood wide web’. This notion obviously made a deep impression: ‘Occasionally – once or twice in a lifetime if you are lucky – you encounter an idea so powerful in its implication that it unsettles the ground you walk on.’ Macfarlane’s descents beneath the planet’s surface are about moving beyond human scales of time and space. The allegorical potential of fungi took him further, forcing not just a reconsideration of the temporal and spatial but the limiting frameworks and binaries through which we have historically attempted to understand the natural world.

Underland is packed with adrenaline-charged accounts of heroic explorers and his own near-death deprivations, squeezing between subterranean snags, careering through claustrophobic caverns. The death count is high. But beneath the adventuring lies a deeper exploration of pressing questions around our future survival in an apocalyptic Anthropocene. It is a hard time to be a ‘nature writer’, but Macfarlane unsettles thinking around the genre. As the earth pukes up histories of abuse, writing about encounters with the natural world takes on a darker timbre. He asks how we might reconcile ‘past pain and present beauty’ in a landscape that ‘enchants in the present but has been a site of violence in the past’. The implications of living in the Anthropocene have heightened his sense of urgency and politics, less apparent in earlier books.

As I visualised the many caves and crypts into which Macfarlane descends, I couldn’t help imagining how an Australian version of Underland might unfold. I thought of the strange subterrains of Nullarbor sinkholes, abandoned opal mines and desert dugouts, the drains and chambers of Melbourne’s Cave Clan. I wondered how a writer – perhaps a little more playful and more au fait with uncertainty – might negotiate Indigenous knowledge of Country and the underland of this vast, ancient, less concreted continent.

The radical recent rise in global tourism has increased the traipsing and trampling and pummelling of the earth. Once no-go zones, places like Antarctica, Svalbard, and Chernobyl have already been Facebooked and Instagrammed to death. Perhaps the next wave will follow Macfarlane on journeys to the centre of the earth through its thirty million miles of ‘tunnel and borehole’. At a time when many writers are reconfiguring the genre of nature writing and pushing it to new and interesting extremes, I look forward to reading what will no doubt be another of Macfarlane’s remarkable achievements.

Comments powered by CComment