- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A year after her death, Mirka Mora is still regarded as a ‘phenomenon’ in the Melbourne art world, not least for her vibrant personality and provocative behaviour. Now Sabine Cotte, a French-Australian painting conservator, in this modest account of her research into the artist’s methods and materials, offers a new perspective on Mora’s creative process and the significance of her work.

Mora – a creative innovator until her death at the age of ninety – was a dedicated, self-taught artist who studied the Old Masters and refined her painting techniques. She is widely known for her dolls (soft sculptures), her tapestries, and her murals. People who took part in her textile workshops often report that she changed their lives. Her public art is still visible in cafés, bookshops, railway stations, and on St Kilda Pier, guaranteeing her a continuing presence in Melbourne’s cultural and social life.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

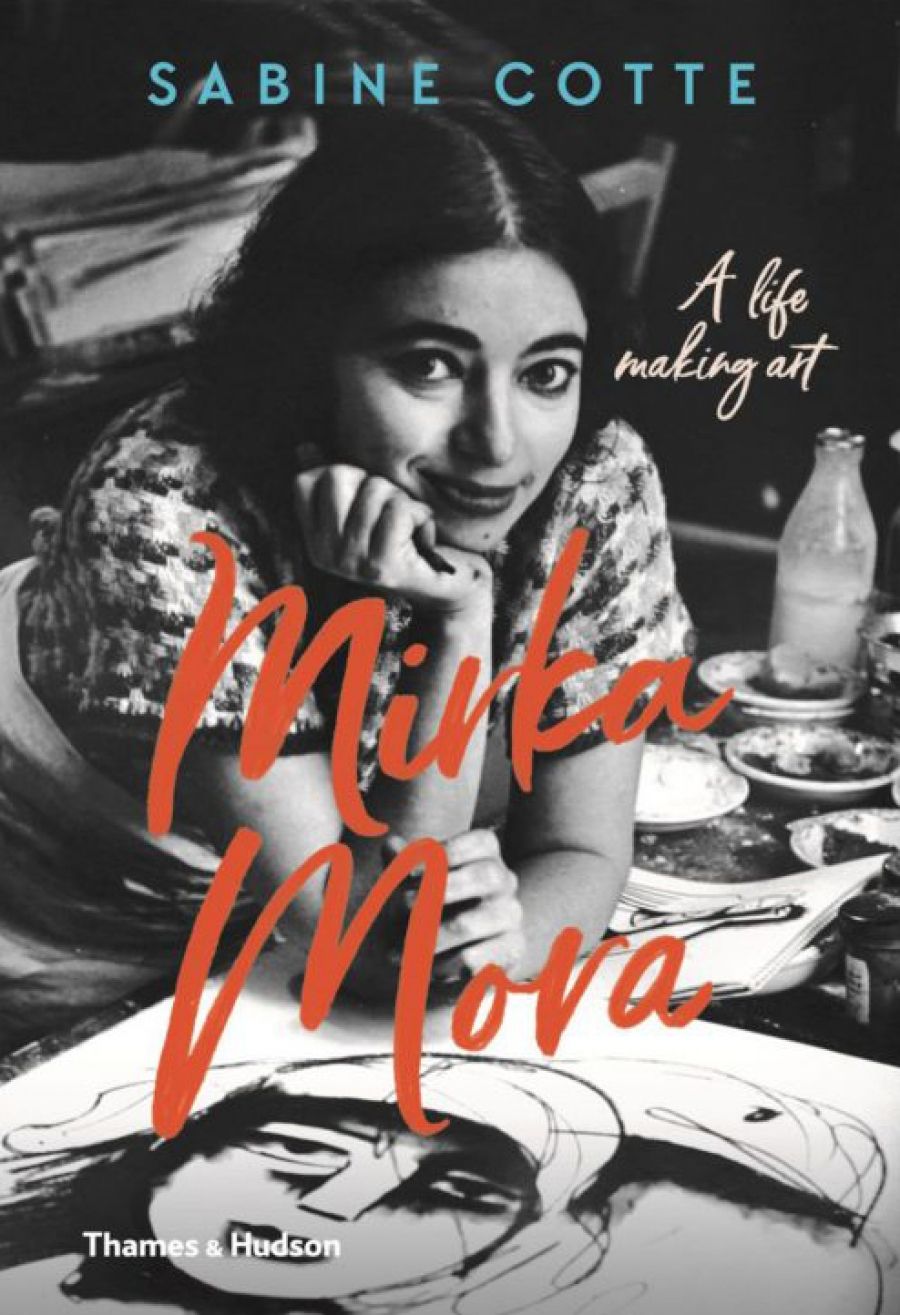

- Book 1 Title: Mirka Mora

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life making art

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $49.99 hb, 256 pp, 9781760760298

Artwork that is displayed in public places is vulnerable to the elements and to contact with human bodies. Sabine Cotte, who worked with Mora to conserve her work in her final years, has written a book about the artist’s processes and materials that illuminates the way for future art historians and curators tasked with restoring or preserving Mora’s work. In this simple yet scholarly account, Cotte eschews the tradition of seeing artists as geniuses and adopts ‘a more human approach to the artist as an innovative maker’.

Cotte’s first contact with Mora was in 2003. Six years later she was commissioned by the National Trust to undertake conservation work on Mora’s Flinders Street Station mural. This was just one of several collaborations between the two women. There is an animated photograph of them, taken during the conservation of the mosaic at St Kilda Pier in 2010, which suggests a close relationship between the two, both born in France and active in the Melbourne art world. Unfortunately, there is little of that animation in the account of their collaboration. Cotte stays distant, ever the observer, keeping the focus on her subject in a way that is both admirable and frustrating. There are some extracts from their discussions on conservation and art, but I would have liked to have been privy to more of their informal discussions and to Mora’s trademark irreverence.

After a brief and impassioned foreword by Mora’s friend, theatre impresario Carillo Gantner, spiced with a few choice anecdotes, Cotte takes up the baton with an introductory chapter about the background to writing the book, which grew out of her research on Mora’s practice and materials for her PhD thesis at the University of Melbourne. Unfortunately, this introduction retains a dry academic tone. It does explain the author’s methodology, tailored to Mora’s personality and using Cotte’s collaboration on the restorations, oral history techniques, her study of Mora’s diaries, and her observation of the artist at work in her studio.

In Chapter One, ‘A Life Larger than Life’, the tone lifts and we are given a fascinating account of Mora’s childhood in Paris, where she was born in 1928 to Jewish parents, a seamstress and an antiques dealer. This may not be new material, but it gives the reader some understanding of her origins and her artistic heritage. On her arrival in Melbourne in 1951 with her husband, Georges, and son Philippe, they became part of the local artistic community and formed lasting relationships with John and Sunday Reed, Barbara and Charles Blackman, Joy Hester and John Perceval. Their famous Collins Street studio was a hub for artists, who were wined and dined lavishly by the European couple.

Mirka Mora, taken in Beamaris 28 May 1961 when she visited the McArdle residence with husband, Georges (photograph by by J. Brian McArdle/Wikimedia Commons)

Mirka Mora, taken in Beamaris 28 May 1961 when she visited the McArdle residence with husband, Georges (photograph by by J. Brian McArdle/Wikimedia Commons)

Mora’s artistic education continued throughout the years she was busy cooking and entertaining guests and raising her sons, both at home and in the cafés that she and Georges started – Mirka Café, Balzac Restaurant, and the Tolarno Hotel. She created a mural ensemble at the Tolarno, filling the bistro’s walls with angels, children, lovers, and mythological creatures. By now she was experimenting with space, volume, and texture, and moving between materials, from paper to canvas to plaster walls.

By 1970 she and Georges were separated and their teenage boys were living with their father. From then on, Mora dedicated herself fully to her art practice. She followed the Old Masters by studying her library of precious art books, learning the rules and then breaking them. Her art – alive, ever changing – reinvented a variety of techniques: fourteenth-century egg tempera in her ‘dough drawings’; soft sculptures and embroidery; mosaic and murals; masks and theatrical sets.

By now the barren days for Australian artists were over, literary and art journals proliferated, and the arts were linked to political idealism and activism, including feminism. Mora chose not to be a militant feminist – she was far too attached to her feminine dresses and beloved dolls, and Cotte does not labour this point. Instead, she demonstrates how Mora expressed the intensity of her personal life through artworks that embodied feminism and the craft movement, as well as community-art policies of the 1980s.

In Mirka Mora: A life making art, Cotte demonstrates her conviction about the importance of doing conservation work in collaboration with living artists, making a clear distinction between ‘refreshing’, to be done only by the creator’s hand, and preservation of the original, the task of conservators. In showing how she worked together with Mora, we are treated to a revealing portrait of this innovative and eccentric artist.

Comments powered by CComment