- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Galileo and Kepler went down in history for prising European science from the jaws of medieval mysticism and religion. But where was England’s equivalent? Newton would not make his mark for another century. Surely the free-thinking Elizabethans also had a scientific star?

They did: Thomas Harriot (c.1560–1621). Most of us have never heard of him, for Harriot did not publish his findings. His day job was teaching navigation to Sir Walter Raleigh’s ship captains. Queen Elizabeth’s favourite was intent on colonising North America for the Crown. But it was also down to Harriot’s personality: retiring, cautious, and meticulous.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

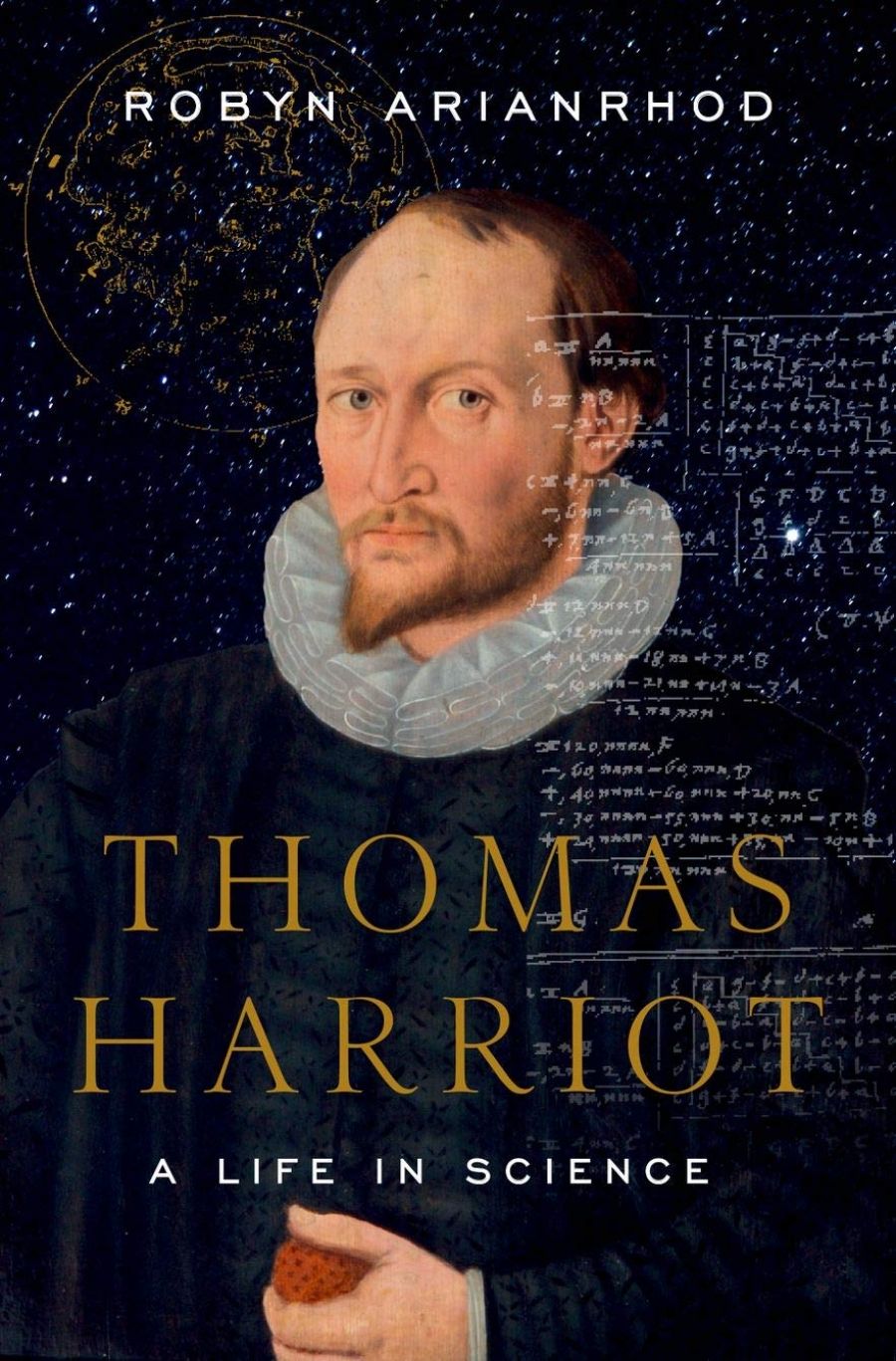

- Book 1 Title: Thomas Harriot

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life in science

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $45 hb, 370 pp, 9780190271855

Harriot was not entirely lost to history. He was famous in his time, so much so that Kepler wrote asking him to share his theory and data on light refraction. ‘Now you, O excellent initiate of the mysteries of nature, reveal the causes.’ For 150 years after his death, most of Harriot’s work was lost. In 1784 his manuscripts were discovered ‘under a pile of old stable accounts’ by a descendant of the ninth earl of Northumberland, his patron. Since the 1950s, historians and mathematicians have painstakingly attempted to piece together Harriot’s contributions to modern maths and science. Now the lay reader has a chance to become acquainted with Harriot thanks to the elegant, vivid prose of Australian mathematician and physicist Robyn Arianrhod. Her previous books, Einstein’s Heroes (2003) and Seduced by Logic (2011), brought her scientific heroes to life: Isaac Newton, James Clark Maxwell, Émilie du Châtelet, Mary Somerville.

Newton famously claimed to have ‘stood on the shoulders of giants’. It was Arianrhod’s attempt to find Newton’s English giant that led her to Harriot. Her quest also unearthed a family connection. Arianrhod’s grandmother, Evareen Throckmorton, often regaled her with the story of their relative Bess Throckmorton, a lady of the Queen’s Privy Chamber who risked her sovereign’s wrath by becoming Raleigh’s lover and then wife.

As only a mathematician can, Arianrhod dives into Harriot’s small, quilled scrawl to witness his mental machinations at work. ‘As I read through Harriot’s pages, sometimes puzzling over them, sometimes smiling with joy at his tours de force, I was moved by the intimacy they afforded.’ The diaries are no dry history. As Arianrhod’s book makes manifest, they resurrect a life lived in science during one of the most fascinating eras in history. The queen deploys a mix of feminine wiles and congenital political cunning to entwine and dominate the power-hungry men of her court. In 1569 Francis Drake has just repeated the first circumnavigation of the world. Now the contest is on with Spain for naval supremacy and for the land and riches of the New World. There is the high culture of the English renaissance. But there is shocking brutality – drawing and quartering is the punishment for treachery – and treachery is rife. There are endless plots to topple the Protestant monarch. Brutal sectarian campaigns see the slaughter of people at home and abroad. Science struggles to gain sway over medievalism, morality over corruption. It’s all recorded by the most iconic writers of the English language.

So where does Harriot fit in?

Navigation by the stars was the hottest topic of the day. At twenty-three, the Oxford-trained Harriot (via a scholarship, since he came from plebeian stock) was held to be the pick of the crop, and Raleigh scooped him up to bring his navigators up to speed. Joining Raleigh’s 1585 expedition to Roanoke Island off the coast of what is now North Carolina, he developed a phonetic system to capture the language of the indigenous Algonquin. His pamphlet A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia (1588) represents the only work to be published in his lifetime. Back in England, finding himself in the orbit of the highrolling young earl of Northumberland, Harriot began exploring the rules of probability, perhaps to demonstrate the folly of gambling to his patron.

Harriot’s exceptional gift for maths and experimentation led him to many firsts, including how to measure the area of curved triangles (what you need as a navigator to travel the Earth’s curved surface), the laws governing the refraction of light and why a rainbow forms, and the laws describing falling objects and ballistic motion, leading to his epithet, the ‘English Galileo’. Mathematically inclined readers will be surprised to discover that he was the first person to solve quadratic equations in modern symbolic form as he leapt ahead with algebra, the abstraction of maths from real objects into an agile language with the ability to divine universal laws, leading ultimately to revelations like E=MC2. He also adhered to atomic theory, as blasphemous in England as heliocentrism was for Galileo in Italy.

Some of Harriot’s proofs are not as polished as the published works of Kepler or Galileo. For Arianrhod, the point of the exercise is not to rank Harriot but to show that he was in their league. The lesson is that science does not advance by the flashing insight of a lone genius; rather, ideas travel like dandelion seeds in the wind, inseminating thinkers across the world.

Maths lovers will rejoice in Arianrhod’s scholarly explication of Harriot’s achievements. But those who are not maths geeks will still find this book an intellectual feast. By threading in Harriot’s story, Arianrhod’s book reveals the full intellectual tapestry of the Elizabethan age.

Comments powered by CComment