- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the spring of 2003, a person from Hilary McPhee’s past got in touch with her. McPhee did not remember the woman’s name but recognised her immediately when they met for coffee. At high school they had played hockey together for a team called the Colac Battlers. The woman had been working for years as a personal assistant at a palace in Jordan ...

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

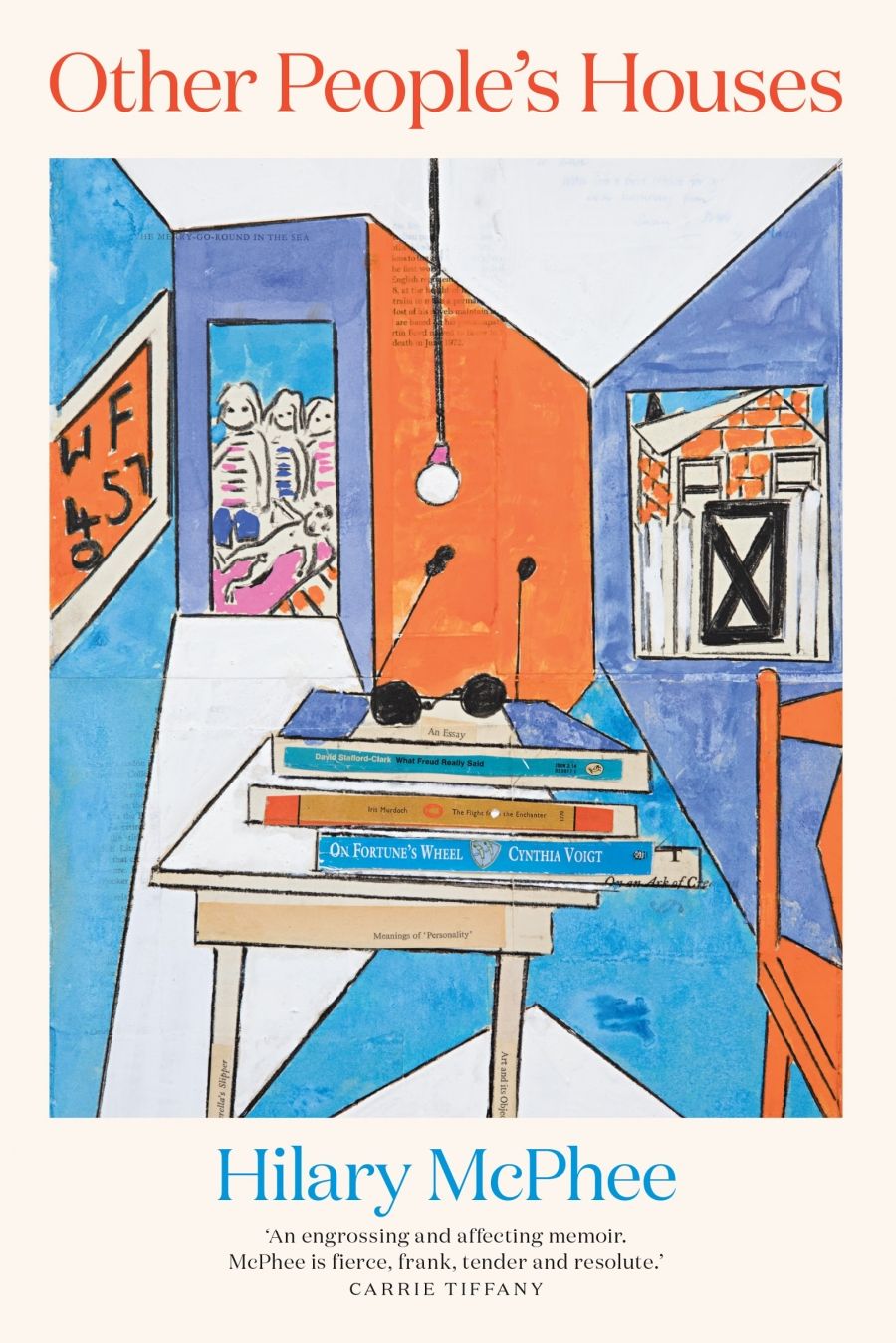

- Book 1 Title: Other People’s Houses

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 226 pp, 9780522875645

When her mother died in 2005, McPhee went to stay with a friend in England. One day her phone rang. The caller identified herself as the London-based personal private secretary of Prince El Hassan bin Talal, the uncle of King Abdullah II of Jordan. Would McPhee go to Amman to discuss writing an autobiography of the prince? First-class air tickets would be arranged. McPhee was not to discuss any of this with anyone. Did she sensibly tell the caller she wasn’t interested, thank you very much? Of course not. It was, she writes, ‘an escape into an adventure that I could not have resisted’.

The prince, her old hockey-playing friend’s boss, was the younger brother of the late King Hussein. The BBC referred to the prince as ‘the voice of reason from a troubled region’. McPhee had no idea why she had been chosen for the job, nor what, exactly, was expected of her. But after her first visit to the royal compound in Amman, she was charmed and intrigued, and agreed to return. Back in Australia, her husband – the writer Don Watson – broke to her that he wanted to end their marriage. A few weeks later, McPhee flew to Amman ‘as if to another planet’.

McPhee’s first memoir was as much about the Australian publishing industry as about her. After a lively description of her girlhood, details of her personal life were scant, and she slipped them in casually, as if they were peripheral to the story. ‘I left Australia in 1965 with a painter who was also a classical guitarist,’ she wrote. ‘We’d been married a few months before …’ Later she mentioned, almost in passing, that after she returned to Melbourne and went to work at Penguin Books, she and her two young children moved in with Penguin’s general manager, John Michie. Later still, she noted briefly the unravelling of her marriage to Michie and reported that she fell in love with Watson. I finished the book full of admiration for McPhee’s achievements and delighted by her turn of phrase – she is a sharp, incisive writer – but feeling that I hadn’t really got to know her.

The new volume has a completely different tone. In part, it is a vivid account of the more than two years she spent in Jordan, interviewing the prince with recorder and notebook in hand, then struggling to put together his book while contending with palace politics and a never fully explained brief. But at heart, Other People’s Houses is an exercise in introspection. McPhee is as always an acute observer, interested in everything that is happening around her, particularly in this case the turmoil in the Middle East. But the central subject here is McPhee herself. She tells us that on the first anniversary of her mother’s death she wrote in her diary: ‘I am motherless, fatherless, husbandless, cracked wide open.’ When she made that entry, she adds, ‘I felt something like wild joy beneath the pain.’

Hilary McPhee in the Umayyad Mosque, Damascus, in 2006 (photograph supplied)

Hilary McPhee in the Umayyad Mosque, Damascus, in 2006 (photograph supplied)

She had never felt so alone, nor so vulnerable. On one of her trips home to Melbourne, her doctor sent her for mammograms, then surgery. When eventually she went back to Amman after a course of radiotherapy, she was advised by her old hockey-playing friend to avoid mentioning cancer because the word carried such stigma. McPhee completely understood. To her, the diagnosis felt like a cause for shame, just as did being left by her husband. In her mind, she had somehow brought it all upon herself. Only after she returned to Australia at the end of the assignment and started picking up the pieces of her old existence did she begin to recover her oomph.

McPhee hasn’t lost her ability to obfuscate. For some reason, the friend who gave her a ukulele to take to Jordan is not identified as the writer Helen Garner. More significantly – and to me, bizarrely – she doesn’t name Watson in this book, referring to him only as ‘my husband’. But it is clear that, at this point in her life, she is in the mood to do some reckoning. She writes that, post-Jordan, she reconnected with Diana Gribble, the once bosom buddy with whom she created the publishing house. The two had always avoided talking about the traumatic end of McPhee Gribble, but once they started they couldn’t stop. For months they met once a week at different cafés: ‘Two women in their late sixties, weeping and raging and clutching each other’s hands before staggering out into the daylight, white-faced in dark glasses.’

What a fabulous image. McPhee’s book, though shot through with regret, is a kind of triumph.

Comments powered by CComment