- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Subheading: The modernist photographer at Spring Forest

- Custom Article Title: Olive Cotton at Spring Forest

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the door to Olive Cotton’s room there is a Dymo-tape label with the name ‘N. Boardman’. Boardman has no relevance whatsoever to Olive’s life story. His name is there because Olive and her husband Ross McInerney’s home – what they always called the ‘new house’ – was previously a construction workers’ barracks. Boardman was one of the occupants, along with Ken Livio and Chris Parris, whose names appear on the doors to adjacent rooms. Olive and Ross, who lived in the ‘new house’ for nearly thirty years, never removed the labels or modified their bedrooms, bathroom, or living areas. This fascinates and perplexes me. Why wouldn’t you erase the signs of those who lived there before you? Why keep them in your most personal, intimate space, your home? What does it mean to live like this? These questions are part of a much larger set arising from my desire to better understand Olive’s life and work, especially during the years when she and Ross lived in country New South Wales, mostly on the property they named ‘Spring Forest’. For much of this time, Olive was invisible to the photography world.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

I was very happy, I loved the space and freedom …

no, I never regretted coming here.

– Olive Cotton, 1998

On the door to Olive Cotton’s room there is a Dymo-tape label with the name ‘N. Boardman’. Boardman has no relevance whatsoever to Olive’s life story. His name is there because Olive and her husband Ross McInerney’s home – what they always called the ‘new house’ – was previously a construction workers’ barracks. Boardman was one of the occupants, along with Ken Livio and Chris Parris, whose names appear on the doors to adjacent rooms. Olive and Ross, who lived in the ‘new house’ for nearly thirty years, never removed the labels or modified their bedrooms, bathroom, or living areas. This fascinates and perplexes me. Why wouldn’t you erase the signs of those who lived there before you? Why keep them in your most personal, intimate space, your home? What does it mean to live like this? These questions are part of a much larger set arising from my desire to better understand Olive’s life and work, especially during the years when she and Ross lived in country New South Wales, mostly on the property they named ‘Spring Forest’. For much of this time, Olive was invisible to the photography world.

Door to Olive Cotton’s room, Spring Forest, New South Wales, 2010 (photograph by Ben Ennis Butler)Coming to terms with the years Olive spent at Spring Forest is proving to be a complex matter because of the ways they frustrate and confound the biographical process. In Sydney, between 1935, when she produced Teacup ballet, and 1945, when she concluded her stint managing the Max Dupain Studio, she was recognised as one of Australia’s leading modernist photographers. When artist Margaret Preston needed a photographic portrait, it was Cotton she approached, relaying in her handwritten note that publisher Sydney Ure Smith says ‘you are the one and only photographer’. Giving form to Olive’s life and work during this period is relatively straightforward because of the abundance of rich, diverse documentation. She was part of a dynamic group, a community of photographers and arts-interested individuals whose experiences and stories are on the public record. But once Olive moved to the country the situation changes completely. Her biographical shape becomes curiously insubstantial, shadowy at best. There are of course many reasons for this. Her photographic activities were curtailed due to her personal circumstances: marriage, motherhood, physical and social isolation in the country, and lack of money. She didn’t open her photography studio at Cowra until 1964, and even then she remained obscure in the larger photography world because of her rural location and her focus on commercial photography.

Door to Olive Cotton’s room, Spring Forest, New South Wales, 2010 (photograph by Ben Ennis Butler)Coming to terms with the years Olive spent at Spring Forest is proving to be a complex matter because of the ways they frustrate and confound the biographical process. In Sydney, between 1935, when she produced Teacup ballet, and 1945, when she concluded her stint managing the Max Dupain Studio, she was recognised as one of Australia’s leading modernist photographers. When artist Margaret Preston needed a photographic portrait, it was Cotton she approached, relaying in her handwritten note that publisher Sydney Ure Smith says ‘you are the one and only photographer’. Giving form to Olive’s life and work during this period is relatively straightforward because of the abundance of rich, diverse documentation. She was part of a dynamic group, a community of photographers and arts-interested individuals whose experiences and stories are on the public record. But once Olive moved to the country the situation changes completely. Her biographical shape becomes curiously insubstantial, shadowy at best. There are of course many reasons for this. Her photographic activities were curtailed due to her personal circumstances: marriage, motherhood, physical and social isolation in the country, and lack of money. She didn’t open her photography studio at Cowra until 1964, and even then she remained obscure in the larger photography world because of her rural location and her focus on commercial photography.

Olive’s lack of a public profile in the immediate postwar period wasn’t unusual among women of her generation, who were expected to give up employment and become wives and mothers. But Olive’s situation was exacerbated by her quiet nature, her reserve, her modesty. It is not at all surprising that there are no public pronouncements on photography or public commentary from the early Spring Forest years – indeed, Olive rarely spoke in public throughout her whole career – but I was not expecting the paucity of private documents that remain from this time. There are no diaries and only a few personal papers and letters. The main primary documentation that exists is Olive’s reminiscences, which came later, in the 1980s and 1990s, when she reappeared in the world of photography. This was when she was recorded in oral history and gave several interviews to journalists, curators, and photography historians. But there is a twist and a very unusual one at that. The ‘new house’, which Olive and Ross purchased in 1973, is still intact.

Visiting the home or homes of your biographical subject is a standard ploy, part of the biographer’s immersion into all possible aspects of their subject’s life. I see it as being intrinsically linked to the physical journeying – the ‘footstepping’ – that English biographer Richard Holmes writes about so well. The assumption is that the retracing and immersive processes, coupled with the scrutiny of personal papers and public works, will provide a means of accessing and understanding the subject’s interior life; a way of forging an empathic connection with their thoughts, feelings, states of mind.

By any measure, Spring Forest should be a boon. Olive died in 2003, and Ross seven years later (both were aged ninety-two), and their house is as they left it. Their things are where they always were: their clothes are in their bedrooms, beds are made, books are on the shelves, jars of preserved fruit are in the pantry, towels are hanging over the bath in their shared bathroom. There is no sign of the ritual sorting out and cleaning up that usually follow someone’s death. Outside, little has changed either. In the front yard, Ross’s assortment of broken-down cars, mainly Austin 1200s and 1800s, which peaked at seventeen by our count, still fills the space between the new house and the front gate to the property. There is a dry cleaner’s van and the remains of a Buick that had been a wedding present from Olive’s father. Tools, machinery, wood heaters, fencing wire lie where I remember them, on the ground and in between the house’s brick foundations. Around the back are more vehicles, more farm machinery, stoves, plastic plant pots, sections of beehives, and other paraphernalia.

I have been visiting Spring Forest for twenty-eight years, first as a curator of photography, then as a family friend, and now as Olive’s biographer. In my new guise, Spring Forest has been transformed from a lived-in environment to something akin to an archaeological site. In its latest incarnation, it has one overwhelming characteristic – excess. It is quite literally laden with artefacts. If all the things cramming the house and yard were sounds, the noise would be deafening. This has a curious and paradoxical effect. I find myself struggling with apparently contradictory states, with both an excess and a lack. In this surfeit of stuff, I am not sure where to find Olive Cotton.

View of the ‘new house’ from the driveway, Spring Forest, NSW, 2010 (photograph by Ben Ennis Butler)

View of the ‘new house’ from the driveway, Spring Forest, NSW, 2010 (photograph by Ben Ennis Butler)

For me Spring Forest raises a host of unanswered, perhaps unanswerable questions. How did Olive, whose photographs are distinguished by their highly refined, elegant aesthetic and focus on essentials, ‘inhabit’ this crowded, seemingly chaotic environment? How did she make sense of her city and country lives? How, in this isolated spot in central-western New South Wales, did she keep her creativity alive? I should tell you at the outset that these questions make me anxious. Not because I am afraid that there will be too few pointers to Olive’s interior life – this is a common dilemma among biographers, and I am happy to work with gaps – but because I might discover something I don’t want to: evidence of prolonged unhappiness, for example, or worse, signs of a thwarted life. What if the larger social forces in the postwar period that drove women back into the home, or Olive’s own character and life choices, conspired against her? What if her reserve and patience weren’t the virtues others praised but impediments that prevented her photography from thriving?

A few weeks ago, Olive’s daughter, Sally McInerney, and I spent a rainy day retracing Olive’s life in Sydney. In Hornsby, from the side of the road, we viewed the house where Olive grew up. It was designed by her parents, Florence (née Channon) and Leo Cotton, at the time of their marriage in 1910. Even by today’s standards the house is huge, irrefutable, and impressive evidence of Olive’s privileged background. She and her four siblings enjoyed all the advantages of a genteel upbringing in a family that prized education and had deep-rooted interests in science (Leo Cotton was appointed professor of geology at the University of Sydney in 1925), art, and music.

While Olive’s early life was obviously very comfortable, what strikes me most is how coherent her interests were and how exceptional she was. In her final year at MLC Burwood, which she attended from 1921 to 1929, she was senior school prefect (equivalent to school captain) and was awarded the School Prize and the prestigious Old Girls’ Union Prize. She excelled in English literature, loved poetry, and wrote some highly romantic poems of her own, was an accomplished pianist, and, even as a teen, demonstrated her talent for photography. When an aunt gave her a camera at the age of eleven, it triggered what Olive described as ‘a great awakening’ as she sensed photography’s potential for self-expression. Her seriousness of intent was evident in her decision to join the Sydney Camera Circle and Photographic Society of New South Wales in 1929 when she was eighteen years old.

She went on to university and completed a Bachelor of Arts in 1933, with majors in English and Mathematics. However, rather than pursuing a teaching career as her father had hoped, she made a pluckier, less conventional decision and joined Max Dupain’s newly established photographic studio. She and Dupain had met in late childhood – both their families had holiday houses at Newport, north of Sydney – and shared their love of photography. They were romantically involved from 1928 onwards: in the few surviving love letters, notes, and poems from the early stages of their relationship, she was his ‘dearest Lassie’ and he her beloved ‘Laddie’.

Olive Cotton, photograph by Morton Colyer, (From Olive Cotton: Photographer, by Helen Ennis, National Library of Australia, 1995)

Olive Cotton, photograph by Morton Colyer, (From Olive Cotton: Photographer, by Helen Ennis, National Library of Australia, 1995)

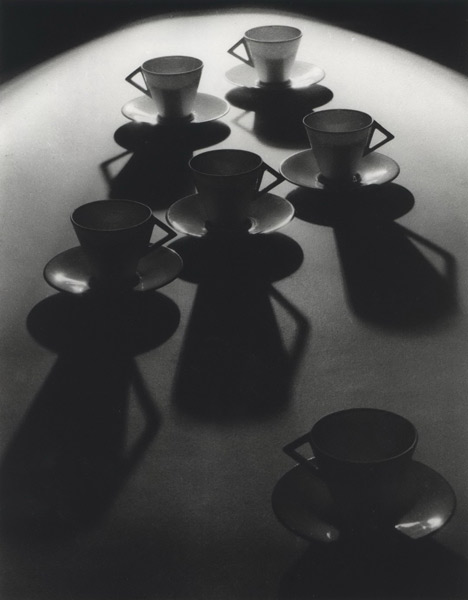

At the Max Dupain Studio, Olive was the general assistant rather than a photographer, her role reflecting the gendered division of labour that was characteristic of the photographic industry at the time. Her duties included making appointments, attending to the models, assisting with the processing of Dupain’s negatives and prints, and re-spotting his prints. However, she made the most of her after-hours access to superior facilities and equipment and in her first five years at the studio produced a fine, varied body of work comprising still lifes, portraits, flower studies, and landscapes. Teacup ballet (1935), long cast as her signature image, was just one of her triumphs (I regard it as atypical in an oeuvre dominated by images drawn from the natural world). Shasta daisies, The sea’s awakening, Papyrus, Max after surfing, and Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind are some of the others, thoroughly resolved works that are intense, complex, poetic.

During this brief period, Olive was one of the few Australian modernist photographers who managed to achieve both a national and international profile. She participated in exhibitions organised by photographic societies in Victoria and New South Wales, and three of her photographs were included in the prestigious London Salon of Photography exhibitions (Teacup ballet was first in 1935). The London showings, she later said, represented the height of her ambition. Her landscape Winter willows was selected for the British publication The Penrose Annual in 1938 and praised for its artistic qualities. In addition, Olive was the only female member of the Contemporary Camera Groupe formed in 1938 to advocate modernism in photography and design, and contributed to their ground-breaking exhibition held in Sydney late that year.

I recently reread Olive’s Year Six (now Year Twelve) English literature exercise books. They plot her journey through the literary canon, from Chaucer and the Metaphysical poets, to Jane Austen and the nineteenth-century English novel, the Romantic poets, and so on. Her essays were warmly commended by her teachers. One exercise book contains a kind of youthful manifesto:

Have you ever tried to count up all your crowded hours? … those times when you have enjoyed yourself to the very utmost. Something set me thinking the other day, when we were discussing whether we would rather be persons who would feel intensely – feel radiantly happy, perhaps only for a fleeting moment, yet a crowded moment, but in time of trouble or sorrow, would suffer deeply … or whether we would rather be mediocre, and neither live intensely nor suffer deeply …

I would rather the former, for I think ‘one crowded hour of glorious life is worth an age without a name’.

(The quotation comes from Thomas Osbert Mordaunt’s poem ‘The Call’, more evidence of her predilection for English poetry.)

In the 1930s Olive clearly enjoyed an abundance of crowded happy hours, capped by her marriage to Dupain at the Cotton family home in Hornsby, in April 1939. Even though they had been close for more than a decade, their marriage was notoriously short-lived, and Olive’s ‘crowded hours’ took a different, unexpected turn as she dealt with separation and the public humiliation of a high-profile divorce. In 1941, after leaving Dupain, she taught mathematics at Frensham, a private girls’ school in Mittagong, which, under the inspired headship of Winifred West, was known for its progressiveness and support for the arts.

What caused the marriage to break down? It is never possible to know what transpires between a couple, and Olive and Max were extremely discreet about their private lives. From Olive there is nothing more on the subject than an anecdote and a few comments published late in life, when her relationship with Dupain was a source of considerable public interest. The anecdote told to me fourth-hand is this: Olive once confided to a close friend that whenever Dupain left the studio in Clarence Street she would rush to the rooftop to look down into the street and see which way he turned – whether he was heading off to visit a client or whether he was on his way to visit a girlfriend. I can imagine her face flushed, her heart in her mouth. As for the public comments, in the 1990s she enigmatically remarked to journalist Susan Chenery, ‘Things alter when you become a wife.’ She told Janet Hawley, for Good Weekend, that by 1941 she had ‘had enough of Max paying rather too much attention to pretty models’.

While Olive and Max didn’t publicly discuss their divorce, they had to endure the attention of the weekly tabloid Truth. An article, ‘Business As Usual: But Not on Home Front’, published on 21 February 1943, reported on the ‘strange state of affairs in the matrimonial lives of Maxwell Spencer Dupain (thirty-two), well-known Sydney photographer, of 49 Clarence Street, and his pretty wife, Olive Edith Dupain (30)’. Dupain, who, according to the article was seeking a ‘restitution of conjugal rights’, told Mr Justice Edwards in a letter presented to the court that ‘Mrs. Dupain has left him and refuses to return’ despite his repeated attempts to induce her to do so. While the justice ordered Mrs Dupain ‘to return to her husband within 21 days’, she did not comply. The divorce went ahead and Olive had to face not only the stigma associated with being a divorcée but also the loss of her job at the studio and the prospect of a financially insecure future. Characteristically, Olive bore Max Dupain no ill will. In an interview for HQ magazine in April 1991 she said, ‘I was with him from 12 to 20 [in fact it was much longer] and I don’t regret those years a bit because he was probably the best friend I could have had and I learned a great deal from him.’

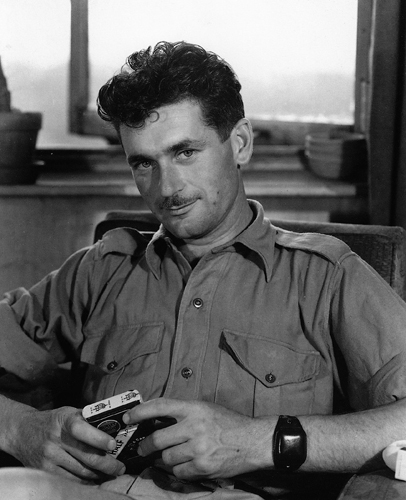

It was through her close friend Jean Lorraine, one of Dupain’s favourite models, that Olive met Ross McInerney, a confident, handsome, charming young man who would become her second husband. Jean was married to Ross’s older brother John, a medical student (who was also known as Jack). In 1942 Olive photographed Ross in the studio while he was on leave from the army and later explained matter-of-factly: ‘After that we saw more of each other whenever possible during the war years, and we married about two-and-a-half years later.’ In many ways, Ross was a curious choice of husband. He was seven years younger than Olive and, in part because of the disruptions caused by war, had not yet established his line of work. He was from the country, the second eldest in a large, colourful family of Irish stock that had been farming in the Cowra region since 1863. Although theirs was a wartime marriage and they hadn’t been able to spend much time together, Olive’s feelings for Ross are abundantly clear in the letters she sent him while he was based in northern Queensland, and which, fortunately, he kept. On 14 February 1945, for instance, six weeks after their hasty marriage in Sydney when Ross had a few days’ leave, she declared: ‘I love you so very much, – do come back safely, my husband, because I just wouldn’t know how to go on living without you. I love you always, Dearest, Olive.’

Ross McInerney, 1942, photograph by Olive Cotton (From Olive Cotton: Photographer, by Helen Ennis, National Library of Australia, 1995)Another episode in Olive’s Sydney life proved crucial. For the last three years of the war she managed Dupain’s studio while he served in the camouflage unit in Papua New Guinea (because of the couple’s cool relations the arrangements were negotiated by Ernest Hyde, whose photo-engraving firm was in the same building as the studio). Olive was one of thousands of women who relished the unprecedented employment opportunities during the war, describing them as ‘really great years’. For the first time, she was able to practise as a professional photographer, issuing work under her own stamp ‘Olive Cotton, Max Dupain Studios’. Her repertoire expanded rapidly as she worked on diverse commissions ranging from portraiture, flower studies, photographs of works of art, to war propaganda. In this period, though incredibly busy, her friendships with other unconventional and creative women flourished, including Jean Lorraine, Maida Annand (wife of artist Douglas Annand), Olga Sharp, and artist Joy Ewart. Ewart’s portrait ‘Miss Olive Cotton’ was a finalist in the 1945 Archibald Prize and was exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Ross McInerney, 1942, photograph by Olive Cotton (From Olive Cotton: Photographer, by Helen Ennis, National Library of Australia, 1995)Another episode in Olive’s Sydney life proved crucial. For the last three years of the war she managed Dupain’s studio while he served in the camouflage unit in Papua New Guinea (because of the couple’s cool relations the arrangements were negotiated by Ernest Hyde, whose photo-engraving firm was in the same building as the studio). Olive was one of thousands of women who relished the unprecedented employment opportunities during the war, describing them as ‘really great years’. For the first time, she was able to practise as a professional photographer, issuing work under her own stamp ‘Olive Cotton, Max Dupain Studios’. Her repertoire expanded rapidly as she worked on diverse commissions ranging from portraiture, flower studies, photographs of works of art, to war propaganda. In this period, though incredibly busy, her friendships with other unconventional and creative women flourished, including Jean Lorraine, Maida Annand (wife of artist Douglas Annand), Olga Sharp, and artist Joy Ewart. Ewart’s portrait ‘Miss Olive Cotton’ was a finalist in the 1945 Archibald Prize and was exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

'Her biographical shape becomes curiously insubstantial, shadowy at best'

While Ross had originally assumed that they would stay in Sydney after the war and the end of Olive’s tenure at the Max Dupain Studio, she decided otherwise. Her precious photographic negatives, prints, and books were packed into a trunk and sent to the country (this blue sea-trunk sits in a corner of the lean-to of the cottage at Spring Forest; the photographs were removed years ago, but it is still full of books of plays, poetry, and fiction). Some of Olive’s photographs were published in 1946 in Helen Blaxland’s book Flower Pieces and in Sturt and the Children’s Library, which depicted the activities of children in different craft workshops and the beautiful gardens. In 1947 Olive was represented in the yearbook Australian Photography, which formally marked the conclusion to her Sydney life and work. Little else would appear in public, in either publications or exhibitions, for decades.

This back story highlights Olive’s relatively privileged background and her significant accomplishments, resourcefulness, and adaptability, but underlines her determination and unconventionality as well – reflected in her decision to join the Dupain Studio, divorce Max Dupain, marry Ross McInerney, and move from a comfortable life in Sydney to the bush. What is also apparent is that Olive went to the country as a mature woman who had experienced disappointment and heartache, but one nonetheless filled with hope for the future after the longed-for end to the war. On 2 April 1945, a few months after their marriage, she wrote to Ross:

Do you remember all my talk of not being sure whether I’d be happy away from the city? It all seems so silly now, and I can hardly believe that I ever doubted the way of living in the country. Oh Darling, I do long to begin everything with you.

It is at this juncture that an account of Olive’s life and work loses its substance and legibility, so far as biography goes. There is the dearth of documentation I have already mentioned, as the clamour and colour of the Sydney years evaporates overnight. There are no more letters from the likes of artist Margaret Preston, ballerina Hélène Kirsova, publisher Sydney Ure Smith; no more encounters with artists and writers such as William Dobell, Arthur Murch, and Eleanor Dark. But more problematic for me, given that Olive’s attraction as a biographical subject is her art photography, is the fact that there’s none to speak of from 1946 until 1964. As a biographer, these are the years that worry me most.

However, it isn’t true to say that Olive lost her desire to take photographs during this time or that she banished photography from her new life. It’s not even true that her photographic practice went into abeyance. She hung on to it as best she could in a life now filled with children – Sally, born in 1946, and Peter two years later – and running a home. At the age of eighty-seven she told Janet Hawley: ‘I still kept taking photographs with my old Rolleiflex camera and had the negatives developed at the town chemist, always with the thought that one day I might get a darkroom of my own and be able to print my negatives.’ She had in mind a book on the subject of childhood in the country and assiduously gathered potential images for it, and every year she made a Christmas card from a photograph of her own children. Her sister-in-law Haidee McInerney suggests that throughout this period her love of photography remained profound, ‘overshadowing everything’.

There is much about Olive’s postwar experiences that was standard for women of her generation. Once the men had returned from war service, women’s participation in the workforce shrank and they were expected to devote themselves exclusively to the roles of wives, mothers, and homemakers. But her circumstances were also highly unusual, and militated against any real prospect of her pursuing art photography. Look for a moment at this black-and-white photograph taken in the late 1940s, which makes the situation clear. For three years Olive, Ross, and their two young children lived in this tent, which they pitched on Ross’s parents’ property in the Ilunie Range, forty-five kilometres south of Cowra. The tent, pictured here in snow, had a wooden floor custom-built by Ross. Nothing could provide a starker contrast with her comfortable Sydney life, but apparently there was a familial precedent for Olive’s revocation of a comfortable material life for love and idealism. Her paternal grandmother, the fabulously named Evangeline Mary Geake Lane, who was also from a well-to-do family, lived with her new husband, the social reformer Frank Cotton, on the New South Wales goldfields when they first married.

Around 1949 the McInerneys rented a small house in the foothills. In 1951 they purchased the five-hundred-acre property Spring Forest that had on it a two-room weatherboard cottage. This would be their home until 1973, when Ross successfully tendered for two demountables that had housed construction workers during the building of the Carcoar Dam near Bathurst. Hauled to Spring Forest and installed a stone’s throw from the old cottage, they formed the ‘new house’. With no electricity, running water, or what Olive herself referred to as ‘mod cons’ for twenty-five years, carrying out basic chores was time-consuming. Under these conditions, processing film and printing at home were clearly impossible and any alternative, such as renting a studio or paying a printer, was out of the question. The McInerneys were poor – almost deliberately, perversely so.

Tent in snow, NSW, c.1946–49. (photograph courtesy of Sally McInerney)

Tent in snow, NSW, c.1946–49. (photograph courtesy of Sally McInerney)

When Olive and Ross moved to the country it was with the intention of purchasing their own property and making a living through farming. However, as it transpired, Ross was not your typical farmer. In Hawley’s colourful words: ‘As his neighbours ringbarked, slashed and burned, shot wildlife, sprayed chemicals, grew crops and grazed cattle, McInerney propagated native trees and plants by the thousands, and helped his forest and the native fauna regenerate.’

'The McInerneys were poor – almost deliberately, perversely so'

Spring Forest was mainly uncleared native bush, and the McInerneys elected to use only a small section of the land, largely for their own domestic purposes. Ross, who was extremely capable, physically strong, and mechanically adept, earned a living of sorts as a labourer, shearer’s cook, by raising a few calves, and, in later years, selling organic honey. Those who knew him well have pointed out to me that he was a conservationist before his time and that his conservationism was idiosyncratic and sometimes contradictory.

It was not only Olive’s material circumstances that were difficult. Spring Forest was nothing like the twenty acres of bushland in Hornsby where she had grown up. It is an often harsh environment, with biting winters, long hot summers, and periods of frequent drought. The property was also isolated, for years accessible from Cowra only by dirt and gravel roads, and there was no phone line until the 1950s. Olive neither drove a car nor rode a bike. She lived hours away from family and friends in Sydney. Aside from members of the extended McInerney family living and farming nearby, she had little other company. Nor did she have much in common with neighbours and locals, as Sally McInerney explained in her essay ‘Life in the Country’ (1995):

Olive was not much like other mothers; she never had her hair permed in the style of the times, never joined any rural groups or associations and did not surpass herself at primary school picnic days when tables groaned with a dazzling display of cakes and biscuits [... She] never learned, or wished to learn, to ride a horse or milk a cow, and the behaviour of dogs was distasteful to her; nor did she feel motherly towards the intemperately bleating ‘poddy’ lambs brought in beside the fire in winter, that kept scrambling out of their cardboard boxes and getting under her feet while she was trying to prepare dinner.

As I have come to see it, Olive’s early life at Spring Forest was shaped by a series of complex adjustments, to an unfamiliar natural environment, the land and weather, the after-effects of war, which those around her dealt with in very different ways, marriage and motherhood, as well as a materially difficult domestic life. But I suspect the greatest challenge – and accommodation – was living with Ross.

I have been taking note of the phrases and words people use to describe Olive. These are some that recur: ‘kind’, ‘humble’, ‘modest’, ‘self-effacing’, ‘warm’, ‘gentle’, ‘saintly’ (‘a saint for putting up with Ross’), ‘patient’, ‘quiet’, ‘reserved’, ‘sensitive’. Ross described Olive as tolerant and stubborn; she was the most truthful person he had ever known. He also told me that in all their years together he never heard Olive speak ill of anyone. Her sister-in-law Haidee concurred, saying that Olive never said anything derogatory or uncharitable about people, and always looked for the good in them.

How different the situation is when it comes to Ross. He sparks into life when I am told that he was: ‘domineering’, ‘dominant’, ‘tyrannical’, ‘savage’, ‘charming’, ‘cultured’, ‘smart’. One of his granddaughters, Lucy Lehmann, writes that he was ‘jealous, bitter, bad-tempered’ (the list goes on until it ends with ‘strangely charismatic’). Ross’s father apparently said that his second-oldest child wasn’t happy unless he was on centre court, and a nephew recounts how Ross fell out with almost everyone at some point. Some thought he was lazy. His ‘movie-star looks’ are often cited. Ross and his older brother Jack were apparently the best-looking McInerneys, each possessing what has been described as ‘a fatal charm’. Jack’s death in a plane crash in Papua New Guinea in 1954 was a tragedy from which Ross, everyone agrees, never fully recovered.

This is Olive’s story because its pivot is her photography, but Ross cannot be separated from it, for the greater part of her life and work was entwined with his. It is not just a matter of knowing Ross better: I must also understand the McInerneys’ marriage, its particular qualities and dynamic. It’s not possible to comprehend Olive’s late photography otherwise.

Hermione Lee, in her biography of Virginia Woolf (1996), sagely declares that ‘All marriages are inexplicable’. From my observations dating from the mid-1980s onwards, Olive and Ross were companionable. In social terms, however, they were not equal. Ross, a natural raconteur, dominated the conversational space. Olive, in all the time I knew her, never interrupted him or rushed to speak. She was silent in a thoughtful way, or expressed agreement, which I read as being indicative of her solicitousness or of her positive, affirmative attitude towards Ross. She had decided long ago, I think, as part of that subtle, wordless process of accommodation that goes on in a close relationship, to allow Ross this much space at least. So he held the floor, told his stories, and expressed his hard-held opinions and prejudices. And even though, as Haidee pointed out, Olive must have heard some of these anecdotes dozens of times, she never asked him to stop.

From their earliest days together, Olive knew that her second husband was far from perfect. In his wartime letters, his impetuousness, bravado, and restlessness were all apparent, interwoven with his declarations of love. Olive knew of his interrupted service record and that he had been court-martialled in late 1944 for going AWOL. She must have realised quickly that, unlike other members of his family, he would not become a successful farmer and that they would struggle materially. But there was much they shared, including their love of reading, an identification with Labor political values, and especially their endless fascination with the natural world, with the trees and birds, many of them rare species, that graced their property.

They undoubtedly loved each other. Between 1960 and 1964, when Olive and the children were away on their annual holidays at her father’s house at Newport, her letters to Ross always began and ended with endearments: ‘Dearest Darling’, ‘I love you very, very much, my Darling. Olive’. ‘Dearest Darling, I do hope you arrived home safely, and that you weren’t feeling too tired after the trip.’ She added a complimentary postscript to one letter: ‘If you walked in looking bronzed and fit all these others would feel most insignificant!’

Who knows what passed between them in their private space? Or what emerged from the ‘dailiness’ of married life, as Virginia Woolf described it, when ‘a bead of sensation … forms, wh. [which] is all the fuller and more sensitive because of the automatic customary unconscious days on either side’? This is not to say that their life together and companionability were free of disappointments, frustrations, and dramas.

Lately I have been hungry for anecdotes, taking to heart Elizabeth Gaskell’s instructions in her biography of Charlotte Brontë: ‘Get as many anecdotes as possible. If you love your reader and want to be read, get anecdotes!’ But I crave them for another reason. Olive’s goodness has become a screen that hides her from view; accepting, patient – passive? Anecdotes, I trust, will fill in her outline, reveal something consequential about her character, especially her psychology and motivations. Curiously, though, I have been told relatively few – unlike the profusion of stories about Ross – and I have been surprised by what I have learned.

Sally remembers one incident from 1954, when the children were small. One morning Ross reacted badly to the breakfast that Olive prepared. They often ate white bread in milk, sweetened with sugar and boiled up in a billy, but Olive apparently served it ‘once too often’. Ross flung the billy into the garden. Sheepish and chastened after his outburst, he watched Olive pack a suitcase and make preparations to leave. She and the children left on foot. They walked until a neighbour picked them up and drove them to the Cowra railway station. They travelled by train and bus to Newport, where Olive’s father and her stepmother lived, and arrived unannounced.

With this anecdote, recounted with the vividness and indeterminacy peculiar to memory, I am shocked by an unstated fact: the sheer physical distances involved and the difficulties in traversing them. The spontaneous nature of Olive’s decision meant there was no time to make any travel plans. The distance from Spring Forest to Cowra is twenty-five kilometres: Olive set off with two young children, a suitcase, and presumably no way of knowing how they would get to town. This alone indicates her determination to be gone, and be gone quickly. There is another telling detail. Sally remembers her mother changing her clothes before they left. She put on her smartest outfit, a chic linen suit from her days as a working woman running the Max Dupain Studio. (An A-line skirt and tailored jacket in off-white with light purple stripes still hang in Olive’s wardrobe in her room at Spring Forest.)

What went through Olive’s mind during the six-month separation that followed – divorced once already and again experiencing marital difficulty, now with children, no work, no financial independence? Family lore has it that the unworldly, quietly spoken Leo Cotton finally told his daughter it would take ten years off his life if she didn’t return to her husband – not, Sally has explained, because he was conservative, but because he was pained at the prospect of Olive being divorced a second time.

The return to Spring Forest was much less dramatic than their departure. Their life as a family resumed in the tiny weatherboard cottage, and it was unbroken until the children left home in the late 1960s to attend university in Sydney.

In 1959 Olive took a job teaching maths at Cowra High School and became the family’s primary breadwinner. She had not taught since her time at Frensham in 1940–41, but had remained keenly interested in education, encouraged by her maiden aunts Janet and Ethel Cotton. Ethel was involved in early-childhood education, including the free kindergarten movement, and wrote two widely circulated primers on spelling and maths. Olive approached the education of her own children in a creative way, applying some of the principles advocated by her forward-thinking aunts.

‘Mrs Mac’, as her students called her, was a conscientious teacher, but with her gentle manner and soft voice it can’t have been easy for her. One former student described her classes as ‘bedlam’ ; the junior boys played up frequently and wouldn’t listen to her instruction. Olive, who clearly enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of engaging with maths, reported to Ross on the progress of professional development classes that she attended in January 1961:

I’m writing this in the lunch hour, and numbers and geometrical figures still seem to be floating in front of my eyes after the usual solid morning of maths.

I’ve just had two assignments back from this lecturer with ‘Excellent work indeed Mrs McInerney’ and ‘Fine work Mrs McInerney’ – ‘very good work’, ‘Well done, well set out’ on them – most encouraging. I slipped in my proof of Pythagoras for him to see and he was most impressed and made a note of it himself for future use! Anyway these lectures continue to be very good indeed. [18 January 1961]

Olive’s position ended in 1963 when a Diploma of Education became a mandatory teaching qualification. Another means of earning an income was urgently needed. The solution meant that Olive Cotton, the photographer, reappeared after an eighteen-year absence. With the help of family and friends, she opened her own photographic studio, with a tiny separate darkroom, in the Calare Building in an arcade off Cowra’s main street. For the next few years she made a reasonable income through portraiture and school and wedding photography. Much of the work was done in people’s own homes, using natural light whenever possible. There is warmth and artistry in the work she produced, particularly in the portraits of children, which she always preferred to take outdoors. More importantly for this story, the studio meant that at last she could resume her art photography. The same year she opened her studio she contributed five photographs to a group exhibition, Creative vision, at the Willoughby Arts Centre.

Among the clutter in Olive’s living room there was always a flower on display, something she had found close at hand and placed in a little glass bottle. I remember a fallen leaf, red with autumn. Hers were the simplest of displays – you couldn’t call them arrangements, that implies far too much formality – usually just a single specimen shown to its best advantage without any artifice or encumbrance. Given that flowers played an important part in the early phase of her career it’s not surprising that she began photographing them again in the 1960s, both in the studio and in their natural settings. Cherokee rose, quince blossom, salvia, sunflowers: these are not hard-to-come-by exotic flowers and share a simplicity of form. The flowers she photographed are significant for another reason as well: they belong to the natural world, which in contrast to her Sydney years, now became the sole preoccupation in her art photography.

If [my] interest in light and line, form and composition and a further element of meaning, a feeling, all came together (no matter what the subject) that to me was a moment of excitement. (Alas that high moment didn’t always come through in the final print – but sometimes, yes.)

I would not like to be labelled a romanticist, pictorialist, modernist or any other ‘ist’. I would feel neatly confined to a pigeonhole whereas I want to feel free to photograph anything that interests me in whatever way I like.

As a biographical subject, Olive returned to public view in the 1980s, thanks in large part to the pioneering research of feminists Jenni Mather, Christine Gillespie, and Barbara Hall, who curated the travelling exhibition Australian Women Photographers 1890–1950s (1981–82). Her photographs from the Sydney years began to be published again in books such as Silver and Grey: Fifty Years of Australian Photography (1980) and Australian Women Photographers 1840-1960. Teacup ballet was selected for a postage stamp issued in 1991 to celebrate the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of photography in Australia, the same year that Kathryn Millard’s documentary on her life and work, Light Years, came out. In 1985 Olive Cotton held her first one-person show at the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney, supported by a grant from the Australia Council. As the title Olive Cotton: Photographs 1924–1984 indicates, the two phases of her career were now presented as continuous, and examples of her most recent work were shown for the first time.

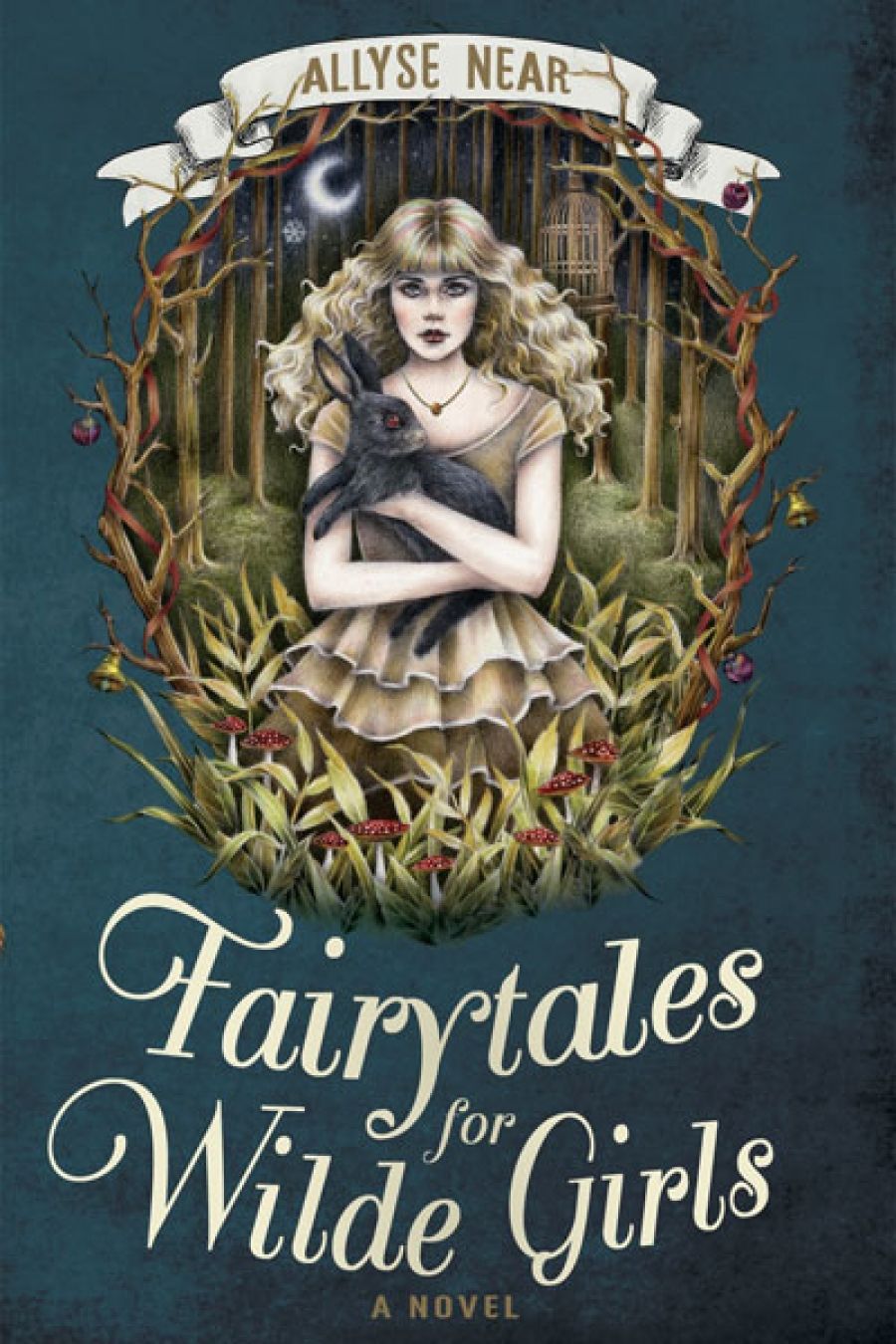

Olive Cotton, Teacup ballet, 1935 (courtesy McInerney family and Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney)

Olive Cotton, Teacup ballet, 1935 (courtesy McInerney family and Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney)

There is no question that this ‘rediscovery’ gave a fillip to her art practice – not that she ever sought the public attention that culminated in the publication in 1995 of Olive Cotton: Photographer or the retrospective exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2000 (I worked on both projects). Olive’s circumstances were right, too. She was no longer taking on commercial work, but she maintained her studio. Once a fortnight during the 1980s and early 1990s, Ross drove her into Cowra and she spent two days there, freed from her domestic responsibilities and the distractions they posed. In her own words:

I can come in early one morning … and I can work all that day and stay at a nearby motel at night and get up early the next morning and come in again …

When you’re home other things are on your mind and you think you’d better stop for a minute and there’s something you should go and do, or what am I going to make for tea tonight.

The interruptions and delays Olive experienced in her creative practice over several decades were not unique. In Nine Lives: Postwar Women Writers Making their Mark (2011), Susan Sheridan points out that some of Australia’s most interesting female writers ‘were not readily visible in the post-war years’ and struggled to combine ‘their artistic and domestic lives’. Elizabeth Jolley was in her early fifties when her first book was published; Olga Masters didn’t achieve her success until in her sixties. Rosalie Gascoigne, who began exhibiting in her late fifties, is a comparable example in the visual arts. Olive, however, was entering her seventies when she regained public visibility, so the larger context affecting the photography isn’t only gender but also her age. Here I think of Käthe Kollwitz, who said: ‘for the last third of life there remains only work. It alone is always stimulating, rejuvenating, exciting and satisfying.’

In suggesting that Olive found herself again in her work of the 1980s, I am not dismissing her early years at Spring Forest merely as a maternal, domestic interlude between two key periods of creative activity. The lack of art photographs from this time unsettles me, but I have become more appreciative of other aspects that may well have nourished her creativity, though the outcomes were deferred. This was prompted by something Sally wrote and has to do with the familiarity and intimacy with her surroundings that she slowly but surely developed, aided by Ross.

Both parents knew the Latin names of plants … we would hear our parents drawing each other’s attention to certain striking trees and cloud formations. It seemed as if Ross, because his family had lived in the district for so long, knew stories attached to every feature of the landscape.

Olive came to know the landscape around Spring Forest well, to love it and ‘the space and freedom’ it provided. In the 1980s the McInerneys arranged to protect their property in perpetuity. It was declared a National Parks and Wildlife refuge, with a covenant that safeguards both the native flora and fauna throughout any changes of ownership in the future.

Olive’s actual physical footsteps aren’t hard to track. She travelled interstate just once in her lifetime, to Tasmania as a high-school student, and she never ventured outside New South Wales after that. She flew in a plane once, and then only above Spring Forest, with Ross’s brother Jack, who was a pilot (and a doctor). One of the aerial photographs she took was published, under her married name, in the ornithological magazine Emu in 1954, identifying the habitat of Gilbert’s Whistlers, a species which Ross (‘A most reliable local observer’) had discovered. For Olive and Ross, Spring Forest was home. In their nearly sixty years together, they never travelled far from it.

However, in the last years of Olive’s life, Spring Forest took on an enlarged meaning, which she explored through her photography. More than ever before, her images became concerned with the rhythms of the natural world and ideas about human impermanence, perhaps not surprising for the daughter of a geologist. Dead sunflowers and Vapour trail are among the late photographs that register a significant shift in her point of view. It is to do with their upward angle and orientation towards the sky. While she had experimented with upward-looking viewpoints in her modernist 1930s work, she tilted her camera even more radically in later decades, not to achieve the dramatic and dynamic effects that were once the object, but to render the images less earthbound.

Vapour trail extends these concerns. It depicts a simple scene Olive witnessed time and again from her vantage point at Spring Forest: the vapour trails of jets flying between Sydney and Melbourne. When she finally photographed a spectacular example, her overriding concern was with a long-distance view, tracing the feathery trail in an expansive sky. More than two thirds of the composition is filled with sky, a narrow band of trees running along the lower section of the image.

I am interested in Edward Said’s work on late style (written when Said was confronting his own mortality) and his consideration of the work artists produce in the final stages of their lives. He challenged the conventional notion that late works, as he put it, invariably expressed ‘a spirit of reconciliation and serenity’, and suggested that they were preoccupied with ‘intransigence, difficulty and contradiction’. In the late work of Beethoven, Thomas Mann, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, and others, he found what he described as ‘a deliberately unproductive productiveness going against ’. In Olive’s last photographs – hardly profuse but extremely well considered – there is no such attitude. The overwhelming impression her images leave is one of serenity.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in her last photograph (she exposed the negative but, at the age of eighty-four, was too frail to make a print). Moths on the windowpane is a prosaic scene, as the title indicates: a familiar nightly event in warm weather, when moths are ubiquitous. Olive would have observed their massings on the window pane in the dining room countless times and thought about taking a photograph for a long while before she did so, watching and waiting. She chose her viewpoint carefully, positioning her camera to take in the eucalypt outside, a tree so close to the house you can almost hear the wind move through it.

What Olive photographed was ordinary on one level but laden with symbolism on another. Moths are of course associated with mortality, typically living only a few days. During their short lifespan there is much to be done, the attraction to light a destructive diversion, an evolutionary dead end. Aside from the moths and the tree, there are two other crucial elements in the image: the window pane and the light. The artificial light that attracts the moths is inside, with Olive; it signifies the warmth and enclosure of the domestic environment. Outside is the darkness, a sure marker of the natural world and its unstoppable, unbreakable rhythms. Between the inside and outside, light and dark is the glass on which the image – and its meaning – pivots. Totally permeable and insubstantial, it provides not a barrier but a passageway between one state of reality, of being, and another. As I see it, in an understated, yet fully assured manner, Olive achieves an image of great profundity. It doesn’t demand attention, but quietly invites it. Another of Said’s reflections comes to mind here: ‘Lateness is being at the end, fully conscious, full of memory, and also very … aware of the present.’

View of Spring Forest with cars, 2010 (photograph by Ben Ennis Butler)

View of Spring Forest with cars, 2010 (photograph by Ben Ennis Butler)

Olive left Spring Forest in the unhappiest of circumstances. She fell, broke her leg, was hospitalised at Orange, and was moved to a nursing home in Cowra. When she died in 2003, Ross buried her at Spring Forest in the gently rising paddock not far from the new house. Her burial site was marked with a clump of white irises that weren’t visible for long, soon eaten by the wildlife inhabiting the property.

Following Ross’s death and burial at Morongla Cemetery, south of Cowra, in late 2010, Olive’s remains were disinterred and reburied next to his grave. If you go to the cemetery to look for Olive Cotton you won’t find her there. All that’s recorded on her impressively spare, matter-of-fact headstone is ‘O McInerney’ and her birth and death dates.

When Olive was alive and Ross was still living at Spring Forest, I would never have entered Olive’s private spaces, neither her bedroom nor what the family called ‘the piano room’ with the name ‘N. Boardman’ on the door and a key forever in the lock. The piano room was usually shut, though once, when it was ajar, I caught a glimpse of the interior and could see the piano on the left-hand wall and the flood of light from the window. When I did go inside (it was on the day we visited Ross at the nursing home in Cowra a few weeks before his death), I felt uncomfortable entering such an intimate space, though Olive had been gone for years. What struck me was the room’s monasticism. The furniture was functional and plain: a single bed, neatly made, a chair next to it, a wardrobe full of clothes, and the incongruous piano. Olive’s bedroom was similarly spartan in terms of its furniture and belongings: a bed, a chest of drawers, a music cabinet. More than anything, I wanted to find out what Olive saw when she raised the blinds every morning. Her rooms faced the front of the property, looking down towards the now ramshackle cottage that was her previous home, and to the road just beyond it. Standing at her bedroom window, I discovered that her field of vision would have been dominated not by a pleasant pastoral scene as I had hopefully imagined, but by the array of rusty cars.

On a visit to Josef Lebovic Gallery in Sydney earlier this year, among some of Olive’s vintage prints I was surprised to find a proof print of the window that features in Moths on the windowpane. It is a documentary sort of image that accepts the subject as it is. Nothing transformative has occurred or seems likely to occur. This photograph, and some things Haidee said a few weeks ago, have set me thinking about the particular and peculiar environment that Spring Forest eventually became, with its accretions over time. Haidee commented that Olive ‘was happy with what she had’ and that ‘she had another world inside her head’, a world that was ‘secret’.

What if Olive didn’t see what I do at Spring Forest, or what is apparent in the snapshots of the house and yard in this article? What if she didn’t remove the labels from the doors to her rooms because there was simply no need to, because in her world view such little things had no relevance? There may be something here that also goes to the heart of Olive and Ross’s deep compatibility. In ‘Night Thoughts without a Nightingale’, a poem by their former son-in-law Geoffrey Lehmann published in his poetry collection Spring Forest (1992), he imagines Ross in a moment of reflection, alone, on the edge of his land: ‘It’s dusk. / An immense and informative hush of insect noises / proclaims my irrelevance.’

Now I am sure that Olive, though tacit on the subject, felt similarly. However, in their shared recognition of human irrelevance there was also a fundamental difference in outlook that slowly took shape during the Spring Forest years. Ross’s world view was infused with a profound sense of the pathos, perhaps even the futility of human life, but Olive’s was not. Her view of human existence, as expressed through her photography, was optimistic and life-affirming.

I said earlier that Spring Forest was intact and that both the interior and exterior of the new house were as Olive and Ross left them. This is true in one sense, but not in another.

One of my last visits to Spring Forest was on the day of Ross’s funeral. My partner and I walked up the drive, past the abandoned cars, and climbed up the wobbly red brick steps that lead into the house. The door wasn’t locked. It opened awkwardly, as it always had, but the smell that assailed us as we walked down the hallway was new: the pungent odour of possum and rat urine. Evidence of creatures’ nocturnal forays was everywhere. We could hear them in the walls and the roof. Olive and Ross’s belongings were no longer ordered. In the kitchen, Ross’s jars of preserved fruit lay smashed on the floor, their contents ruined. It looked as though the place had been ransacked. I have been back a couple of times since then. The smell in the house has dissipated, windows have been broken, sections of the spouting have come down.

I have wandered around the site in my biographer’s guise looking at the bewildering excess of stuff in the front and back yards, and have found the experience increasingly melancholic and dispiriting. I doubt that I will visit Spring Forest again. There’s no need to, for there is no sign of Olive now. Her photographs are safely stored elsewhere, and everything she left behind has been given up to time, nature, and the elements. I can only presume that is what she wanted. ■

Helen Ennis would like to thank Sally McInerney and the McInerney family for their help with her research.

ABR Fellowships, funded by private patrons and philanthropic foundations and each worth $5000, are intended to generate incisive writing and to broaden the magazine’s content. Helen Ennis’s essay is the fruit of the ABR George Hicks Foundation Fellowship. Click here for more details.