- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

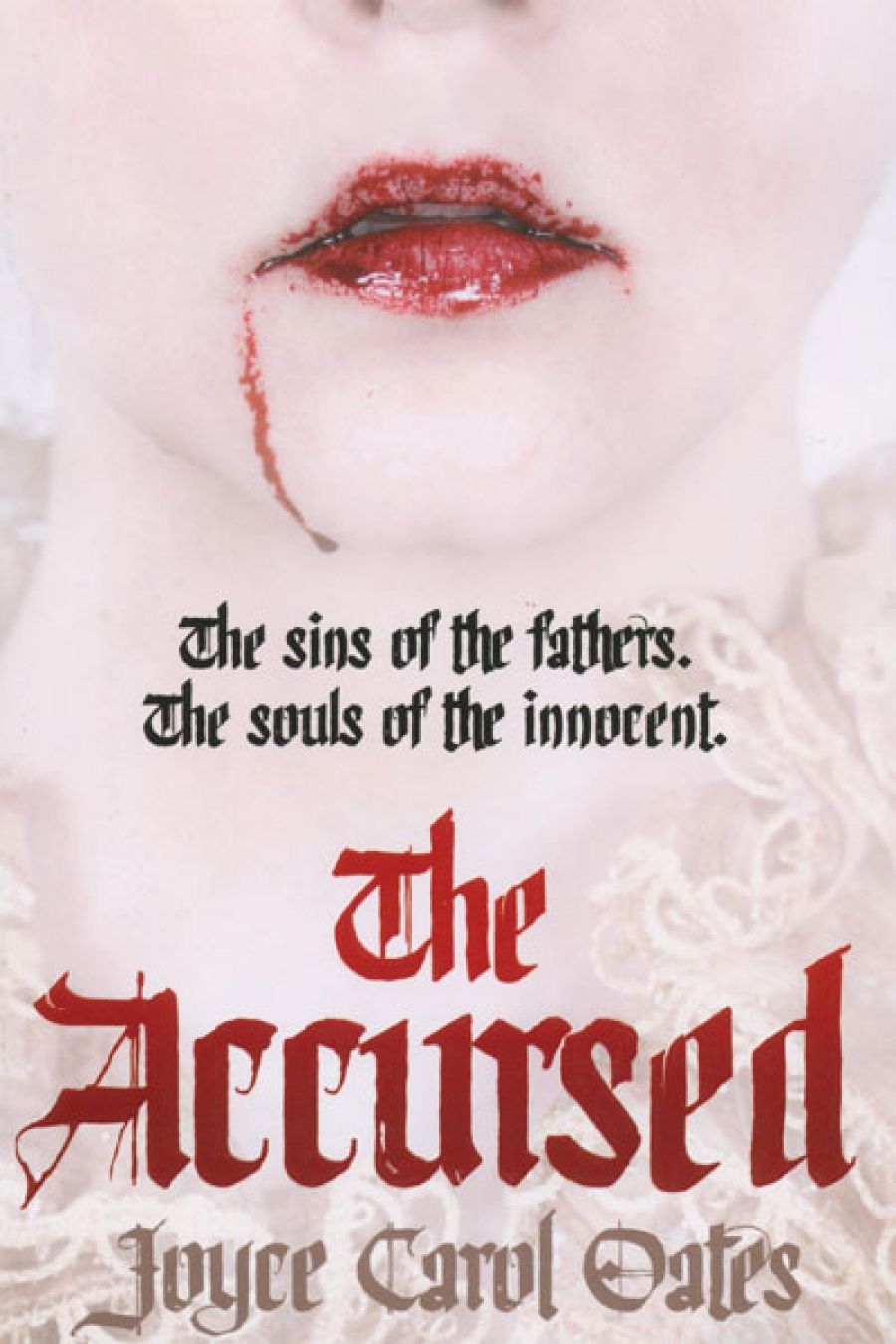

- Subheading: Joyce Carol Oates's new horror novel

- Custom Article Title: Morag Fraser reviews 'The Accursed' by Joyce Carol Oates

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Accursed

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If, hardy reader, you make it through the 667 pages of Joyce Carol Oates’s The Accursed, you will see, on page 669, that she prefaces her acknowledgments with this gnomic utterance: ‘The truths of Fiction reside in metaphor; but metaphor is here generated by History.’

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Accursed

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $29.99 pb, 688 pp

Which it does, sometimes. The Accursed, in its roundabout, encoded way, conveys much of Oates’s outrage at the entangled injustice of American race history, and the shocking persistence of abuse – psychological and physical – of women and children, black and white. She understands, disturbingly, the potential corrosiveness of Puritan rectitude and Puritan guilt – the novel is a litany of damage done by repression and its Janus face, violence. Her social conscience rings loud in her fiction and offends all the right people (the American gun lobby would like to see her waterboarded). Plus, she has technique to burn. Oates can spin (and spin and spin) a tale. She can do satirical and she can do wicked. And voices – the climax of The Accursed is a sustained piece of high-pitched confessional oratory that rivals Peter Carey’s bravura rhetorical ventriloquism in True History of the Kelly Gang.

So why then, after two intense days with Joyce Carol Oates’s conjurings, did I turn with such relief to Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic classics? It wasn’t because The Fall of The House of Usher runs to only fourteen pages in my inherited (1927) edition and The Murders in the Rue Morgue to twenty-six (I remember them as full-length novels). It was, I think, to confirm a memory of focus, of a coherent imagined world. Poe’s narrative voice is singular, curious where Oates’s is knowing. His Gothic lyricism is not laid on but grounded in experience, authentic, as here:

I looked upon the scene before me – upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain – upon the bleak walls – upon the vacant eye-like windows – upon a few rank sedges – and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees – with an utter depression of soul, which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveller upon opium – the bitter lapse into everyday life – the hideous dropping of the veil.

(The Fall of the House of Usher)

Where Poe is exploring a genre, Oates is toying with one. The Accursed is like a gigantic doll’s house, a mansion with doors that open and shut upon snakes-and-ladder staircases and revolving tableaux of historical characters, some sinister, some hysterical, ranged against painted backdrops that change at random, and the whole edifice built over dungeons and cess pits that are transparent and occluded by turns. The house has too many tour guides, encyclopedic, opinionated, and unreliable.

Set in New Jersey’s famed university town of Princeton, The Accursed retails the (fictional) history of a moral blight that descends upon the town’s well-heeled west-end residents. In 1905, Annabel Slade, lily-white daughter and granddaughter of one of Princeton’s élite families, and connected to Princeton’s university president (and soon to be US president), Woodrow Wilson, flees from the altar on her wedding day with a dusky demon lover called Axon Mayte (‘Axon’ was the maiden name of the real Woodrow Wilson’s first wife – Oates is not a writer to pass up an opportunity).

Mayhem, shame, and confusion ensue. Did the virginal Annabel jump or was she abducted? The tale’s principal narrator, one M.W. Dyke II, descendant of another of the town’s esteemed families, is still ambivalent at his time of writing (in 1986): ‘…we cannot know if we act or are acted upon; whether we are playing pieces in the game, or are the very game ourselves.’

Oates’s ‘playing pieces’, a lively, bewildering mix of invented and ‘real’ characters, don’t know either. Her Woodrow Wilson is assailed by demons of hypochondria, racial fear, and paranoia. But as he will not publicly condemn the Ku Klux Klan, his sufferings – indeed those of the whole town – appear like condign punishment. The (fictional) Slade dynasty, from its patriarch, the Reverend Winslow Slade, to the youngest grandchild, is struck down by ‘The Curse’ – or by their own waywardness or guilt or surreal adventuring. Grandson Josiah, the novel’s version of doomed hero figure, escapes his cursed, cosseted Princeton life to go wayfaring in the world of Upton Sinclair, American politics, environmental activism, Jack London, and – why not? – polar exploration with the brother of Titus Oates.

It is all very clever, Hogarthian in its excess (a grotesque Teddy Roosevelt even larger than in life), and endlessly inventive. But finally, nothing in The Accursed – not even a walk-on appearance by Sherlock Holmes – surprises. And that’s the problem.

Comments powered by CComment