- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

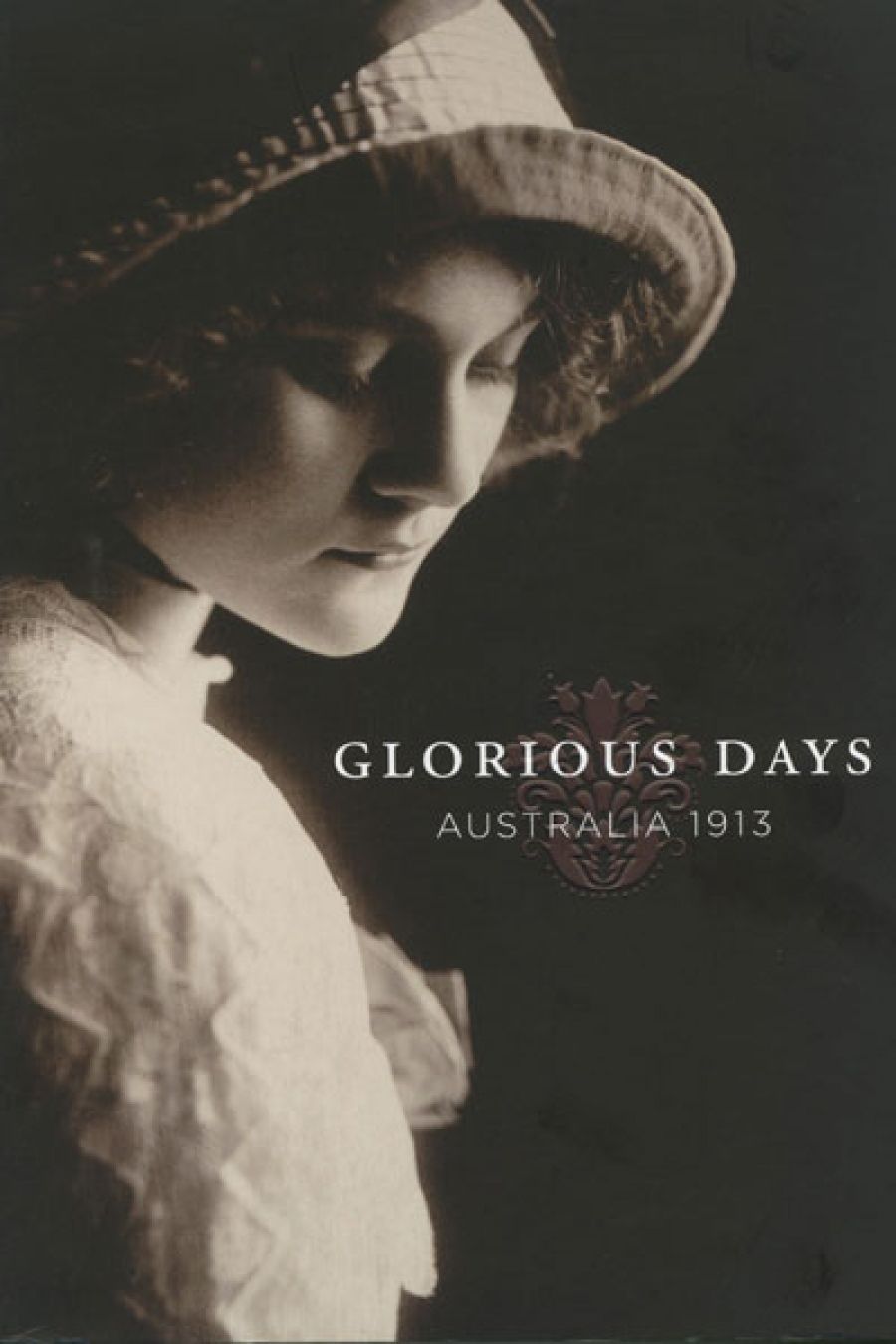

- Custom Article Title: John Thompson reviews 'Glorious Days: Australia 1913' by Michelle Heatherington

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The way we were

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Not altogether surprisingly, the centenary this year of the foundation and naming of Canberra as the national capital of Australia has passed without any conspicuous celebration of the event beyond the confines of the city itself. Conceived to embody and represent the aspirations of the new Australian nation, unfettered by the rivalries and jealousies of the states, Canberra has always been held in grudging regard by the very nation it was established to serve – the grudge perhaps greater than the regard.

- Book 1 Title: Glorious Days: Australia 1913

- Book 1 Biblio: National Museum of Australia, $44.95 pb, 249 pp, 9781921953064

The sorry story of the bickering over the capital – finely delineated by historian Nicholas Brown – sits somewhat uneasily with the expansively optimistic title of this book of essays, which was commissioned to accompany the celebratory exhibition of the same name presented by the National Museum of Australia (NMA) as its contribution to the centenary of its host city. But if the title is extravagant, there is no argument about the idea itself – to present a snapshot of Australia in the year in which Canberra was named. As Andrew Sayers, director of the NMA, observes in his foreword, the centenary is the pretext to pursue a larger purpose: to look at the shape of Australian life one hundred years ago as the country entered the modern age and, it is implied, before the dreadful blooding in World War I blighted its prospects and dashed its optimism. With sixty thousand dead out of Australia’s pre-war population of four million, rebirth and recovery would not be achieved for generations. In his pioneering cultural history From Deserts the Prophets Come: The Creative Spirit in Australia 1788–1972 (1973), Geoffrey Serle characterised the years between the wars as a marking of time for Australia and the era from c.1900–30 as ‘a curiously disappointing period of delayed development, false starts and unfulfilled talents’.

The NMA’s closer reading of the year 1913 suggests that, for a short time at least, Australia had seen the first green shoots of what might have been a national efflorescence had the fates been different. The tone for this national pulse-taking is set by the epigraph, a stanza selected from Henry Lawson’s For Australia (1913), with its expansive vision: ‘And glorious were the songs we sung / In those grand days when hopes ran high.’ Editor Michelle Hetherington has assembled an impressive list of sixteen contributors to examine the texture of Australian life either in 1913 or in the span of years leading up to it. This was a time, she says, when the nation was embracing the modern age with vigour, when it was eager to learn, to develop, to dream, a time of achievements and ambitions too soon eclipsed by the darkness that followed.

Perhaps it is simplistic to draw such a stark dichotomy between two eras, the years before the war and those that followed. History is never so tidy, but fortunately Hetherington’s contributors, all seasoned historians in their respective fields, understand this. The impulse to celebrate is tempered by stern judgement and important qualifications, a recognition that Australia was still in formation, an outpost: a young country, dependent and provincial, its culture imitative rather than original. Arranged in three sections – ‘An Australasian Empire’, ‘Land of Opportunity’, and ‘Life in Edwardian Australia’ – the essays range broadly to present a rich, enticing, and at times depressing view of the young Australian nation only recently federated and feeling its way in the world. These wide-ranging essays include surveys of the political and financial landscapes, the state of labour reform, the pursuit of a feminist reform agenda, Indigenous affairs, and styles of domestic living. Helen Ennis provides a masterly account of the state (and popularity) of photography in a suite of essays that examine leisure and popular culture, the visual arts (in a pairing of essays by Andrew Sayers and Howard Morphy, with the latter’s splendid account of Aboriginal bark painters and weavers in Arnhem Land and the adjacent Tiwi Islands an important redress of past neglect of this field), and music. The NMA’s Guy Hansen writes well on sport, noting the development of a mass spectator following and the emergence of the professional sportsman.

Australia in 1913 was still profoundly British, emphatically racist, and highly unsympathetic to the needs of its First People. A distant outpost of the empire, it was nervous in its isolation and its island vastness, and had ambitions to assert its authority in its region, especially in New Guinea and Antarctica. At home, with labour regulation and with improved national earnings, Australians were revelling in their increased leisure and their country’s healthy climate. Sporting prowess was seen as proof of Australia’s greatness as a nation, while the arts, too, suggested promise. In certain ways, though, the country seemed to lack confidence or the bravura touch, too often setting its sights too low. W.K. Hancock, in his precocious but deftly judged survey volume Australia (1930), could observe that the national capital was a ‘triumph of the middling standard’, testament to a society that itself had settled for the pursuit of ‘average satisfactions for average people’. The sad failures and compromises of the Canberra story say much about Australia still.

Independent publishing by cultural institutions in Australia can be a mixed blessing, particularly where design is concerned. The best results seem to come when institutions combine with commercial publishers under a joint imprint, allowing quality editorial content and illustration to be presented to their best advantage (a good recent example is Richard Neville’s Mr J.W. Lewin: Painter & Naturalist [2012] published jointly by the State Library of New South Wales and NewSouth Publishing). While Glorious Days is stylishly designed and handsomely illustrated, the book is let down by poor production standards. At the end of my careful handling, the review copy I had received in pristine condition was looking decidedly the worse for wear, with vertical creases weakening and cracking the spine, and with the cover detached from the book along the front inside gutter. Such flaws detract from a book that its editor hopes will prove an entertaining and valuable resource long after the exhibition Glorious Days: Australia 1913 has ended (it runs until 13 October 2013). These essays deserve a longer life, but it is a pity this solidly priced paperback is a poor vehicle for the journey.

Comments powered by CComment