- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Subheading: The phenomenal artistry of the Roentgens

- Custom Article Title: Christopher Menz reviews 'Extravagant Inventions' by Wolfram Koeppe

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: At a single touch

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Such was the esteem of the Roentgens – father Abraham and son David – that fourteen years after David’s death in 1807, Goethe, whose father owned Roentgen furniture, knew that his readers would appreciate the metaphor. Probably not since the Great bed of Ware, c.1590 – referred to by Sir Toby Belch and in Ben Jonson’s Epicœne – had furniture such a famous literary champion. The Roentgens were not just ordinary cabinetmakers. Indeed, they were among the most celebrated European furniture makers of the second half of the eighteenth century.

- Book 1 Title: Extravagant Inventions

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Princely Furniture of the Roentgens

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Inbooks), $99.95 hb, 303 pp, 9780300185027

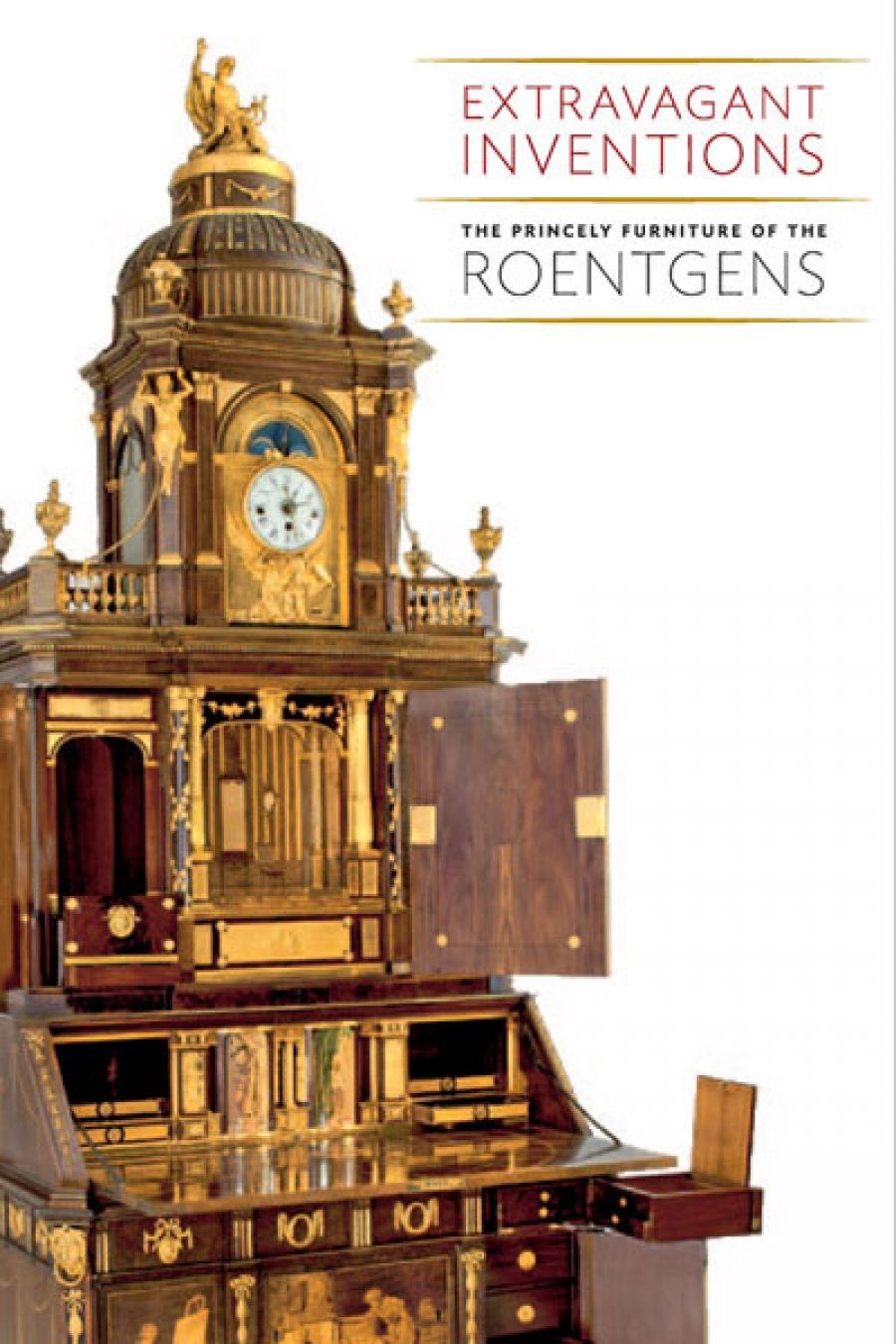

Many of these extraordinarily beautiful, fragile works of art were assembled together in a dazzling exhibition, Extravagant Inventions: The Princely Furniture of the Roentgens, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art over the winter of 2012–13. Highlights included the rococo Writing desk, c.1758–62, made for Count Walderdorff (Rijksmuseum), a tour de force of pictorial marquetry and ingenious concealed drawers; the Berlin secretary cabinet, 1778–79 (Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin); and the Apollo desk, c.1783–84 (Hermitage), the latter two being sumptuous neoclassical creations. Some pieces had never left their original European cities. It is a testament to the Met that it can persuade the great European museums to lend such pieces of furniture. They are, after all, infinitely complex to pack and freight and more prone to damage than paintings. However, it must be remembered that David Roentgen himself transported these exquisite creations across Europe during the eighteenth century in considerably more perilous conditions.

Abraham Roentgen, Writing Desk c.1758–62 (Rijksmuseum)

Abraham Roentgen, Writing Desk c.1758–62 (Rijksmuseum)

Abraham Roentgen was the son of a cabinetmaker. After his apprenticeship, he spent time in Holland and London where he honed his technical and design skills, before returning to Germany and establishing the cabinetmaking business that was eventually taken over by his equally gifted and even more entrepreneurial son. But this family’s distinct contribution to decorative arts might never have occurred, at least not in Europe. Abraham, a member of the Moravian brethren, had married in 1739 and decided to go to North America on missionary work. It was only when the ship transporting him sank, having safely avoided pirates and docked in Galway, that he was persuaded to go back to Germany and rejoin his wife. There he became part of a Moravian community at Herrnhaag where David was born in 1743. The Roentgens, along with the community, eventually settled in Neuwied am Rhein in 1750. ‘Neuwied’ became a generic term for the Roentgens’ work. Unusually, portraits of both Roentgens and their wives survive, an indication of their considerable success and of the changing status of craftsmen during the eighteenth century.

The Roentgens’ style covers the late baroque, through bravura rococo creations of the father to the elegant neoclassicism and Greek revival that the son pioneered from the early 1770s. Their work became famous throughout northern Europe, not only for the refinement of its design and the quality of its execution and marquetry, but largely for the novelty of the extraordinary mechanisms that opened concealed drawers and cupboards, produced bookrests and mirrors, and at times even played music. This furniture clearly delighted and gave great pleasure to its original owners, something that the exhibition and book manage to convey.

Those with the wherewithal of the ancien régime knew how to furnish their palaces. One French text from the early 1780s recommended that for a suitably grand establishment the construction cost of the house should be one quarter of the total allocated, the rest to be spent on the interiors and furnishings. Indeed, the first piece of furniture that David Roentgen sold to Catherine the Great in 1784, the Apollo desk, an elaborate neoclassical model that included a miniature gilded bronze model of the empress’s favourite greyhound, Zémire, cost her the equivalent of a grand country estate with serfs. No wonder Roentgen delivered it to her personally in St Petersburg. She became his greatest patron.

Not only was David a highly skilled craftsman, but he was a brilliant entrepreneur. Well educated, he spoke French as well as German and could thus court his grand clients appropriately. The most magnificent of his surviving creations, the Berlin secretary cabinet, a desk over three and a half metres high that includes a clock, was produced and delivered on spec to Frederick William II, as heir-presumptive to the Prussian crown, in Berlin in 1779. (Such is the scale of this piece of furniture that the Metropolitan Museum had to modify the ceiling of the gallery to accommodate it.) The prince was so impressed with the secretary that he secured it with a down payment which he did not pay off until after he became king in 1786. When the firm was in difficulties due to the financial crisis that followed the Seven Years’ War, Roentgen successfully pursued the risky but not uncommon practice of selling pieces of furniture by lottery: he cashed in on the aristocracy’s love of gambling and the desire for luxury.

This superbly illustrated book has essays by a team of experts, led by Wolfram Koeppe, on a range of the Roentgens’ activities, their lives, and their relationships with key patrons, followed by brief object-specific essays on each of the pieces of furniture included in the exhibition. It is a model publication on decorative arts of the most extravagant and inventive kind.

Comments powered by CComment