- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gender

- Custom Article Title: Paul Morgan reviews 'Fanny and Stella' by Neil Mckenna

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The war on sex

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The trial of Frederick Park and Ernest Boulton in 1870 might have been designed for the media to whip up public outrage in a familiar mix of moral disapproval and prurient detail. As Neil McKenna’s Fanny and Stella reveals, this was indeed the intention of the British government of the day.

- Book 1 Title: Fanny and Stella

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $27.99 pb, 417 pp, 9780571302444

When arrested, young Fred and Ernest were extravagantly dressed and made up as ‘Fanny’ and ‘Stella’. Drunk, they were flirting outrageously with anything in trousers and looking forward to enthusiastic sex with the same in a nearby alley. McKenna tells the story of their trial in a tone that is disconcerting until you realise ‘he do the police in different voices’. Recounting the different perspectives of Fanny and Stella, their families, the press, and police, his voice becomes boisterous, sentimental, and salacious by turn, giving a vivid texture to his tale. The description of a trip to Scarborough by Stella with another lover, Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton, is a set piece of comedy worthy of Joe Orton.

Fanny and Stella is more than an entertaining romp through distant, less enlightened times. McKenna skilfully weaves into his tale a darker narrative of how our understanding of sexuality has been socially constructed by political, religious, and economic forces. The term ‘homosexual’ is only recorded from 1869, and reflects an attempt to impose a paradigm of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ sexuality. This intolerance was part of a wider hysteria about sex during the 1800s. Prostitution, masturbation, teenage sex, promiscuity, anal sex: all were subject to intense legal or medical scrutiny in a vain attempt to proscribe as ‘unnatural’ and evil anything except state-sanctioned intercourse within heterosexual marriage.

All the doubts and anxieties of the Victorian era seemed to settle on the human body. If that could be rigorously controlled, surely so could everything else. As McKenna reveals, the arrest of Fanny and Stella was no accident. The capture and trial of the two young men had been planned for months. Witnesses were already prepared or bribed. The decision to prosecute had come from the highest levels of the government, at the order of the home secretary. The attorney-general himself was to be prosecuting counsel. It is astonishing how frightened the Establishment was of a couple of boys who liked to wear dresses.

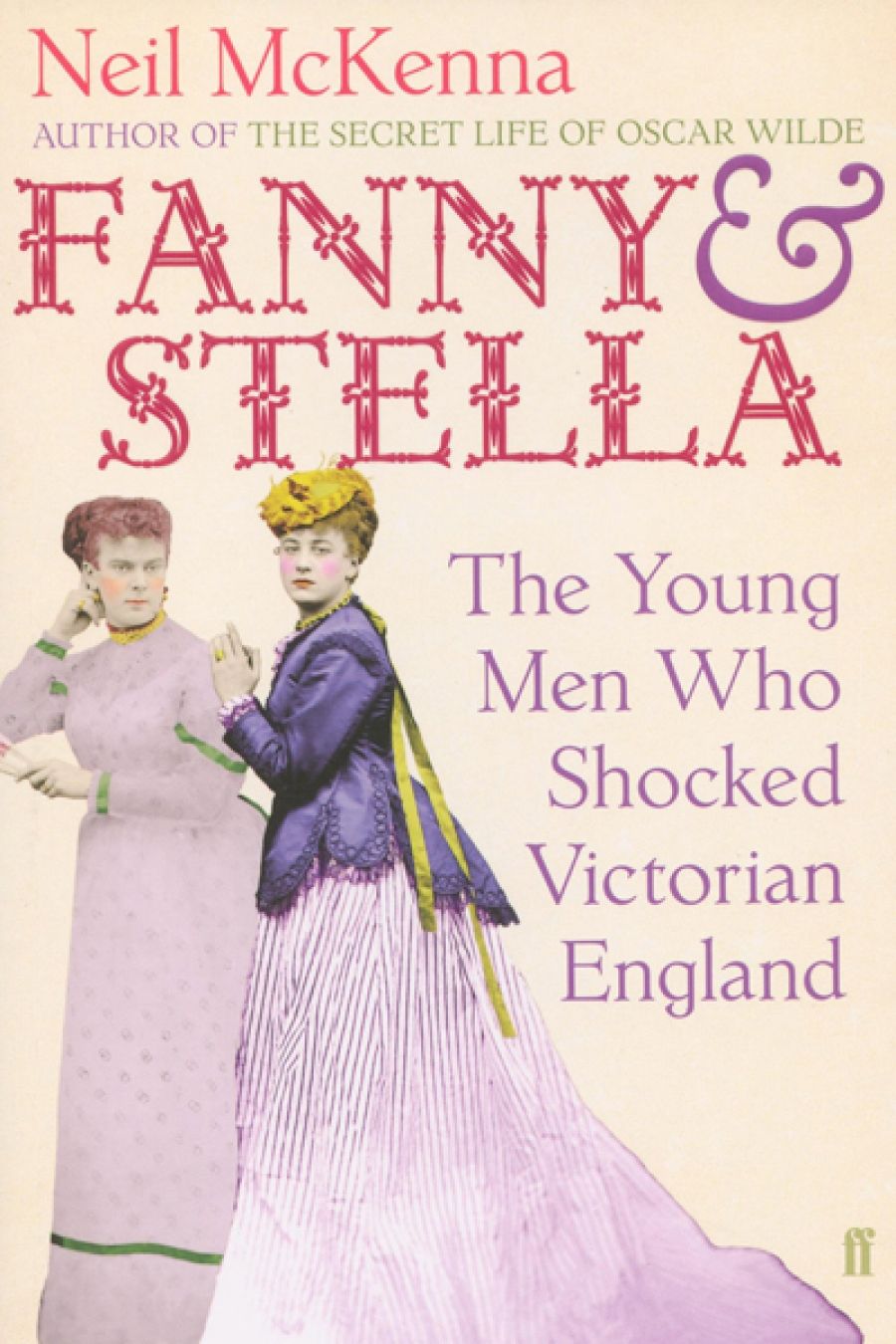

Fanny and Stella, photographed in Chelmsford by Fred Spalding, c.1870 (Photo: Essex Record Office)

Fanny and Stella, photographed in Chelmsford by Fred Spalding, c.1870 (Photo: Essex Record Office)

They may have been targeted because they were so brazen. They seemed to lack any sense of shame. What was worse, they could not be viewed as victims, like ‘fallen women’ who needed saving. Gladstone, the prime minister himself, often walked the streets until midnight, pleading with prostitutes to renounce their life of sin. Both Park and Boulton were from respectable families (the father of one was a judge, the other a stockbroker) and had no excuse for the life they led – getting up in drag and fucking men for pleasure, money, or both. It could not be tolerated. Despite intrusive physical examination by six doctors, however, no medical ‘evidence’ could be procured to prove the crime of sodomy. They were therefore prosecuted for the legally dubious offence of inciting this act.

As the evidence unfolded in court, it became clear that Fanny and Stella were part of a vast underground of illicit sexual activity, with its own clubs, dances (employing blind fiddlers to provide music), and even friendships between female and male prostitutes who set up house together. Could something so common really be called ‘abnormal’? The attorney-general was surprised to see a high-powered defence team, paid for by rich friends of the accused. Lord Arthur was also inconvenient for the prosecution. He was an intimate of the couple (the outrageous Stella had a calling card with ‘Lady Clinton’ printed on it), and even more inconveniently was the godson of the prime minister. With great consideration, Lord Arthur promptly died and was hastily buried (family documents suggest that he was actually spirited abroad with a new identity). Eventually, the case collapsed and Fanny and Stella walked free in triumph. Their trial was a classic case of the hazard of prosecuting people on the basis of who they are rather than what they have done.

It is easy to look back smugly at the unenlightened attitudes of the Victorian period. As McKenna’s account shows, things were more complex in reality. Even in modern times, distrust and fear about sexuality can still flare up with surprising savagery. Well-known examples abound in Australia. The treatment of Eugene Goossens and of Junie Morosi immediately comes to mind. More recently, we have seen Bill Henson, one of Australia’s most respected artists, subjected to hysterical public attacks. Today still, people can be troubled by our existence as embodied beings. Perhaps it is unsettling to be reminded that the conscious mind is not the sole master of our lives, and that maturity – as individuals and as a society – consists in the acceptance of this fact.

Fanny and Stella’s adventures in defiance of the laws and mores of their time demonstrated that this acceptance is possible, as they openly embraced their sexuality without guilt or shame in the most hostile circumstances. Perhaps a statue is in order. There’s always that fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square.

Comments powered by CComment