- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gender

- Custom Article Title: Milly Main reviews 'Just Between Us'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The sting

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Friendship between women is ideal. It is affectionate and nurturing, founded on generosity and mutual love. It is intimate and loyal, because you can tell your best friend anything and she won’t betray you. It lasts a lifetime.

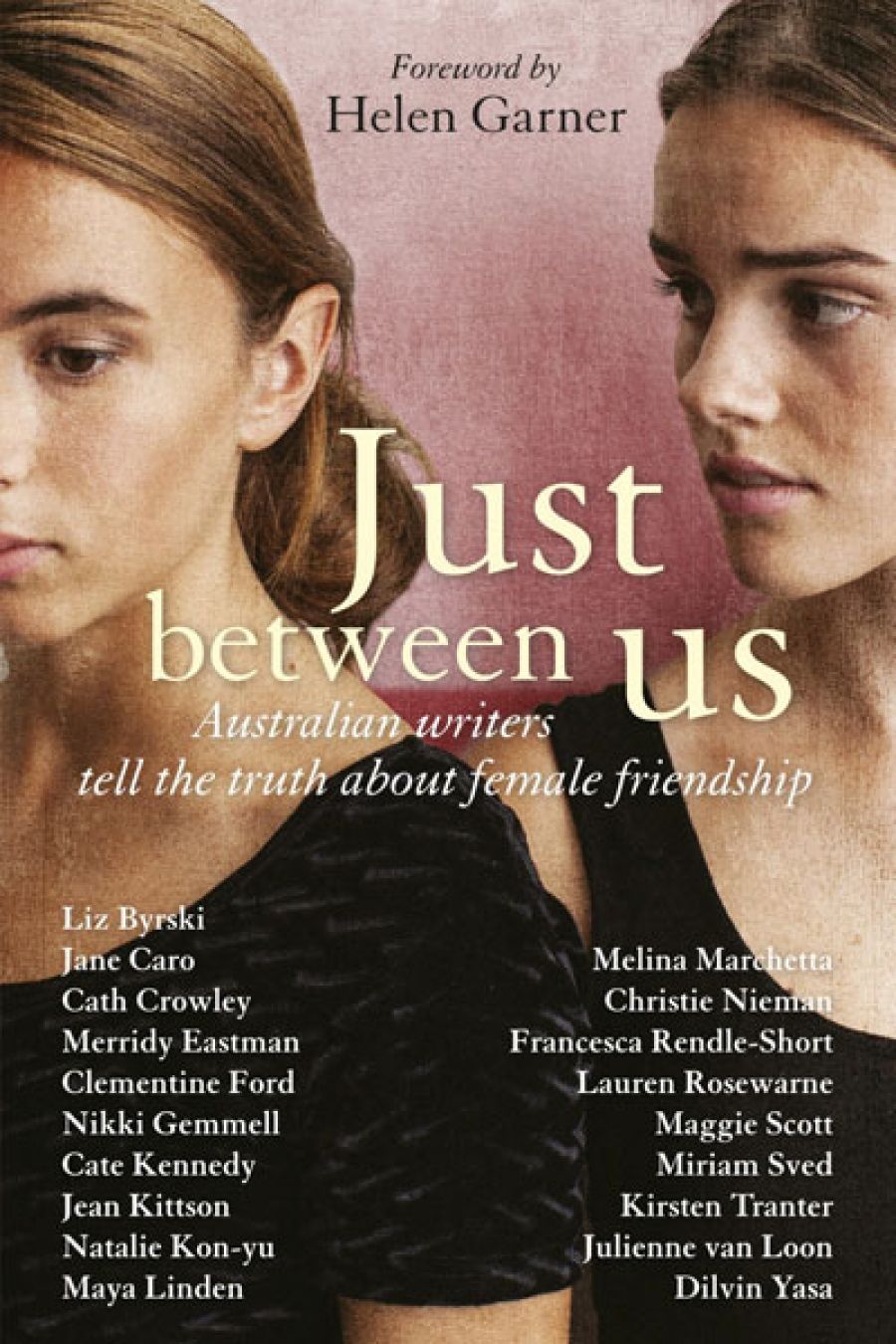

- Book 1 Title: Just Between Us

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian Writers Tell the Truth about Female Friendship

- Book 1 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, $29.99 pb, 352 pp, 9781742612140

This mythical, embroidered version of female friendship and its supposed sanctity appears frequently in themodern folklore offilm, television, and popular fiction. It bears little resemblance to reality. Few women would describe their relationships in terms so sentimental or absolute, or would identify in their own lives the devious ‘frienemy’ of countless soap operas and potboilers who waits until their backs are turned before stealing their men. Just Between Us attempts to redress the lack of cultural narratives about authentic female friendship. Most women, according to the anecdotal enquiries of the editors, have experienced the breakdown of a close friendship. As the memoir and fiction collected here attest, women have an immense capacity to inflict psychological harm on one another.

Women’s friendships are neither irreproachable nor malign, comprised of neither infinite love nor constant spite. As usual, the reality is somewhere in the middle. Based on the experiences of the contributors to Just Between Us, this ambiguity is one of the most troubling aspects of a friendship’s collapse. Many of these narratives describe relationships which peak in the protagonist’s thirties or forties – when a woman raises (or does not raise) children – and which gradually, ineluctably unravel. A woman becomes wealthier and changes suburbs, leaving the other behind. One watches a friend procreate, while she is infertile. Nikki Gemmell describes growing apart from her best friend: Gemmell goes back to work after having children while ‘she’ does not; both shift and manoeuvre as the friendship tries to adjust: ‘Then … Nothing.’ A common realisation: while life goes on, the frog has boiled.

Jane Caro, in ‘The Girl Who Got Smaller’, recalls the fraught demise of her closest friendship, ‘still mired in resentment and unfinished business’. This lack of closure is universal in the memoirs which recount the anxious contraction of a relationship. Resentment becomes a theme. There is a pattern of discordant negotiation, which often lasts longer than it should, distinguished by the brittle anxiety of its participants, who seem unable to articulate their feelings to one another. All of this angst may be unappealing to some. Helen Garner, in her foreword, suggests the tendency of a woman to analyse a small detail or event that a man might overlook: ‘to reveal every corner of its motive and meaning and, by analysing it, to mollify its sting.’ In the many excellent non-fiction pieces collected here, writers such as Caro and Liz Byrski anatomise their experiences with wit, self-possession, and the clarity of hindsight. They turn over the rocks on their friendships and discover the underlying psychological causes of conflict, which are not so much female as human.

Another human flaw, the harmful struggle for power, is also explored in the context of female friendships: the way women seek to control one another, form groups, torment those who stray, and reinforce the hierarchy of the group. Clementine Ford, in a strong, revealing contribution, looks back on the cliquey politics of boarding school. Lauren Rosewarne, a political scientist, describes the adolescent desire to conform in one of the more humorous pieces. Some of the non-fiction works are briefly contextualised in neuropsychiatry or sociology. Gemmell touches on the biological foundation of group politics, and Garner even hints at an evolutionary basis for women’s conduct: it would have been interesting to hear more on this.

In Cate Kennedy’s ‘All Women on Earth Are One Family’, she contemplates nüshu, an extraordinary women’s-only language discovered in China and created for women, by women over generations at a time when they were repressed and otherwise illiterate. Kennedy abandons her initial, romantic interpretation of nüshu, acknowledging that she had wanted to believe that ‘somewhere in the world [friendship] had truly operated in a state of loyalty, fealty, steadfastness and solidarity’. She concludes that modern friendship is comparatively trivial; it is a fascinating, controversial piece. Julienne van Loon’s powerful essay also stands out, for elucidating the genuine love that can develop between women. The epistolary sequences provide some of the saddest moments in the book.

Strong contributions such as these tend to eclipse the short stories. As is vogue, most of the fiction is ambiguous and open to interpretation, which does not satisfyingly address many of the questions raised in the book. As such, it tends to complement the non-fiction rather than shine on its own. Worth noting is Maggie Scott’s fine short story ‘Walk With Me’, about ageing acid ravers going their separate ways, and Christie Nieman’s ‘The Young’, which is graphic and creepy, though perhaps a little too suggestive as the story comes to a head, the protagonist crouching over ‘as her uterus began to spasm and contract’.

Language usually reserved for describing passion and love is frequently used for friendship in the book. Bonds which are so deeply felt become traumatic when they fall apart. What is left – resentment (a word that in its early etymological sense denoted ‘intensive force of feeling’) – can become toxic. Just Between Us offers contemplation, advice, and the occasion for women to be wary of their own power to injure.

Comments powered by CComment