- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Subheading: The rise of an aesthete from Winchmore Hill

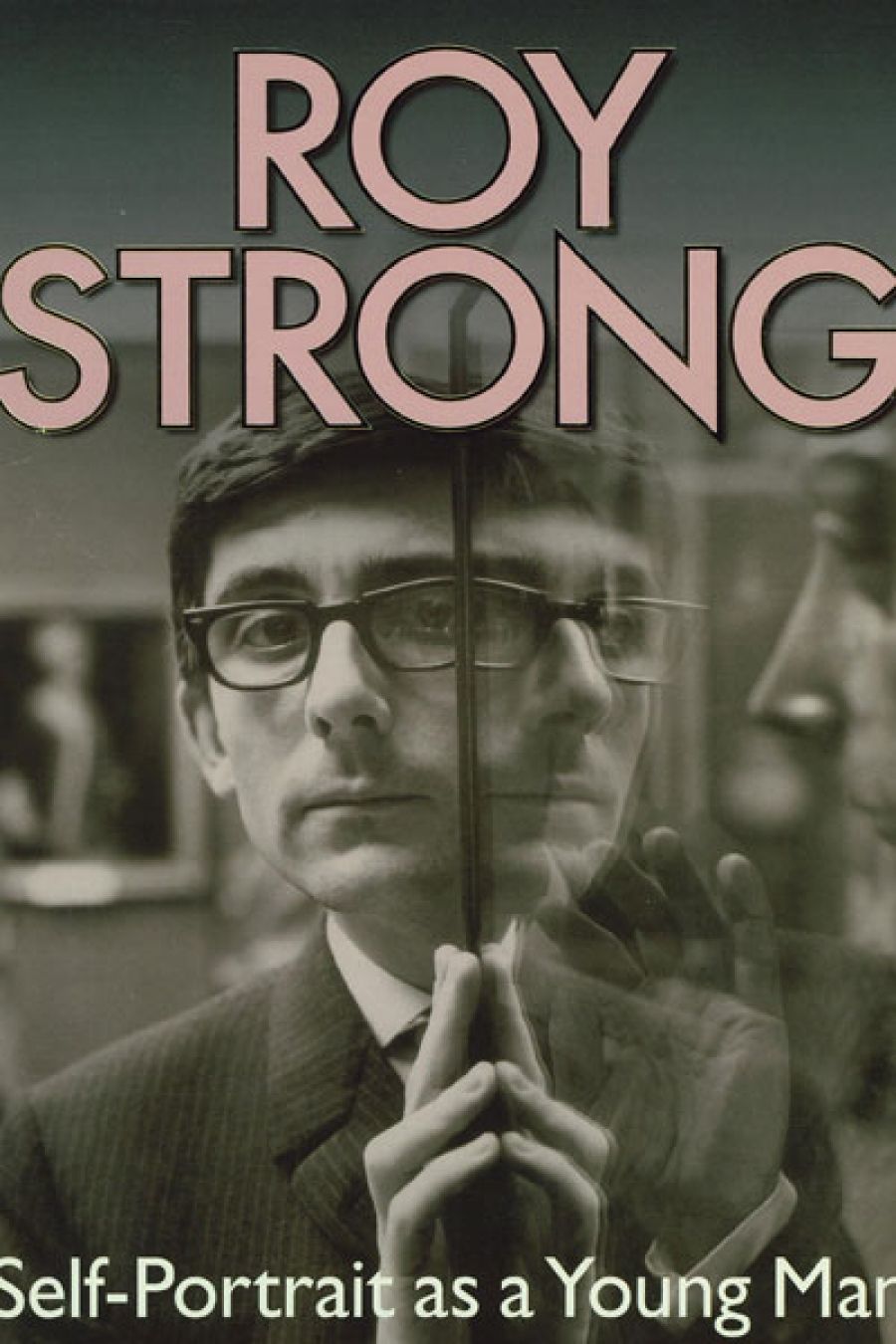

- Custom Article Title: Patrick McCaughey reviews 'Self-Portrait as a Young Man' by Roy Strong

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: From somewhere to nowhere

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Roy Strong was appointed director of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in 1967 at the age of thirty-two. Today it would be astonishing to head one of the United Kingdom’s national collections at that age; five decades ago it was outrageous. Only Kenneth Clark at thirty was younger when he became director of the National Gallery. Strong’s ascent to the NPG has stayed in his mind as the fulcrum of his professional life.

- Book 1 Title: Self-Portrait as a Young Man

- Book 1 Biblio: Bodleian Library (Inbooks), $59.95 hb, 296 pp, 9781851242825

By turns grim and ruefully amusing, sharp edged and touching, Strong’s autobiography traces, vividly and candidly, the story ‘of a young man from nowhere who went somewhere’. He had to battle his way through the British class system and transcend the discriminations that system so freely dispensed.

Roy Strong was born into the lower middle class at 23 Colne Road, Winchmore Hill in suburban North London:

This was the world of keeping up appearances, of front gardens kept in immaculate order, the lawns mown, the beds filled with annuals each summer and the containing hedges of privet neatly clipped … [T]here was a strong corporate feeling as to which rung of the social ladder they occupied. When a house opposite was purchased by a taxi driver who parked his vehicle outside, it was clear the social order had been irrecoverably breached.

Inside 23 Colne Road the atmosphere was no less stifling. Strong’s father was a commercial traveller in men’s hats. His beat along the south coast was virtually destroyed in 1939, and the family impoverished. There was little love between father and son. ‘His return in the early evening always signalled the descent of a pall over the house.’ Strong came to hate his father, a hypochondriac who lived to ninety, for the oppressive atmosphere his selfishness and lack of concern for other members of the family created. Needless to say, he took no interest in the development of young Roy. His mother seems dim but loving; Strong has a lingering resentment at being turned into ‘a mother’s boy’. He notes amusingly her conventional prejudices:‘A black young person once came to the door for my middle brother and extended his hand to my mother … which she had no option other than to shake. She was shattered by the event.’

Freezing in winter, the Strong household had one fireplace and enough hot water for a weekly bath. Strong did not have a room of his own until he was nineteen, and only escaped to his own flat in 1964 at twenty-nine. When he married Julia Trevelyan Oman, the distinguished theatre designer, his mother refused to attend. It was Strong’s turn to be shattered. His marriage, long and happy, wedded a descendant of the Victorian intellectual aristocracy with the purest product of the postwar meritocracy. Strong’s ticket out of Winchmore Hill was the combination of his own high intelligence and immense industry, and the effectiveness of R.A. Butler’s Education Act of 1944. It instituted the Eleven plus exam and, for the successful, a grammar-school education opening the way to university. Strong did well at Edmonton Grammar School in everything except French, and spent two years in the sixth form, where he was well taught and read history intensively. As a boy, he had already developed an independent interest in historical costume and the theatre. At seventeen he was ‘entranced’ when he saw John Gielgud in The Winter’s Tale, directed by Peter Brook, and in Much Ado About Nothing, opposite Diana Wynyard as Beatrice.

C.V. Wedgwood and A.L. Rowse furthered his interest in Elizabethan and Jacobean England, of which he would become the leading art historian. Curiously, even for one so bright, literate, and hard-working, Oxbridge was out of the question. Likewise the Courtauld Institute, partly because it could not take him immediately after his A levels and partly because his family did not appear in Debrett’s.

The grim and inconvenient Queen Mary College (QMC) of the University of London – not even its academically superior University College – accepted Strong into its history school. He recalls his undergraduate years as ‘unremitting slog’. QMC was far removed from ‘towery city and branchy between towers’ of the ancient universities and the commute from North London to the Mile End Road dreary and tedious. But Strong had to take a course in Renaissance art at the Warburg Institute under E.H. Gombrich and Charles Mitchell; the latter would have considerable influence over such distinguished Australian art historians as Bernard Smith. Strong got a First at QMC, good enough to win a scholarship to the Warburg. He wanted to do his MA on the portraits of Elizabeth I, but under the formidable tutelage of Frances Yates shifted around to the Warburgian theme of court festivals, pageants, and masques as a way of interpreting Tudor rule.

Dame Frances Yates, as she later became, was the greatest influence on Strong’s ascent as a scholar of brilliance and insight. She is the subject of the autobiography’s most extended portrait, for the relationship was far from straightforward. In her mid-fifties when Strong came under her influence in 1956, she had been at the Warburg since 1941 and Strong was only her twelfth student. Yates introduced him to ‘a wholly different way of thinking about sixteenth century monarchy’. She encouraged his natural bent to roam intellectually with such remarks as ‘we’ve got to get to the bottom of this Whore of Babylon stuff’. Likewise she encouraged him to apply for his first position at the NPG as Assistant Keeper II, wisely telling Strong to alter his description of his father’s occupation from ‘commercial traveller’ to ‘businessman’. Once there, however, she derided his work as of ‘a lower order’.

The NPG in 1959, when Strong joined the staff, was deadly. The galleries were gloomy and unchanging. There were no exhibitions of consequence, no publications, no education department, and no public lavatories. If a journalist rang, the phone was put down immediately. Strong began to change all that from below with attractive, innovatively designed exhibitions on Holbein and Henry VIII and The Winter Queen (the daughter of James I). Life changed dramatically for Strong when David (‘Pete’) Piper became director in 1964 and virtually handed over the galleries to him to be redesigned and reinstalled. After two years, Piper left the NPG suddenly to become director of the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge. The unexpected opportunity yawned in Strong’s face.

Again there were obstacles. The position was to be advertised with the stipulation that the candidates had to be over thirty-five. Piper and Lord Kenyon, chairman of the Board, had that changed. Strong knew it was his big moment and prepared assiduously for the test. Oliver Millar, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, Francis Wormald, President of the Society of Antiquaries and a distinguished scholar, plus Piper and Yates, were his referees. Strong wrote a considered statement on the new direction the NPG should take. E.H. Gombrich and E.K. Waterhouse were on the selection committee. Strong emerged triumphant, but even at that moment the system struck back. Sir Geoffrey Agnew, doyen of Old Master dealers in London, snapped to his fellow knight and dealer, Hugh Leggatt: ‘No one of that class should have been appointed.’ Harold Nicolson cut Strong dead: ‘We never appointed you.’ Sir Philip Hendy, director of the National Gallery, just round the corner, failed to write the briefest note of congratulation.

Within a year, Strong had mounted the famous exhibition of Cecil Beaton’s portraits. It was a runaway success and launched Strong as ‘the young museum lion’. He became the glass of fashion for the Swinging Sixties. His clothes from that time are now in museum collections. The changes he wrought at the NPG proved lasting. Photography is now collected as well as exhibited. Living sitters are included in the collection. At the NPG, Strong found his theme as a director who could project his institution to a wide public with flair without diminishing its seriousness. A glittering phrase of Sir Philip Sidney’s became ‘the guiding principle of my life’; to purvey ‘the riches of knowledge upon the stream of delight’.

Comments powered by CComment