- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

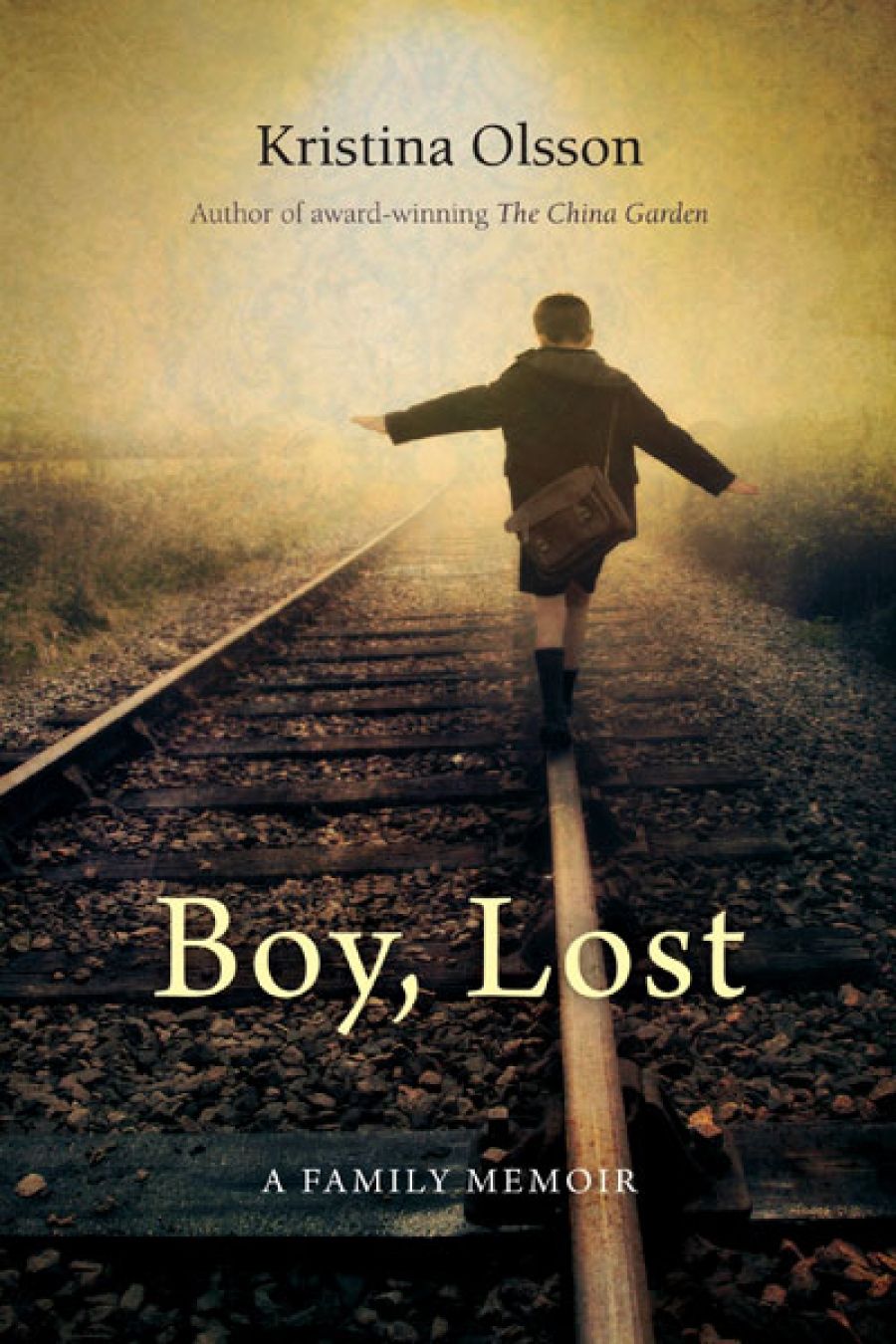

- Custom Article Title: Gillian Dooley reviews 'Boy, Lost' by Kristina Olsson

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Missing childhood

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Boy, Lost is a sad and shocking memoir, unique in particulars but not in broad outline. Domestic violence and psychological sadism lie at its heart.

- Book 1 Title: Boy, Lost

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland, Press $29.95 pb, 258 pp, 9780702249532

Kristina Olsson’s mother lived with the consequences of an act of savagery for which she could hardly be blamed but for which, according to Olsson, she punished herself all her life. Yvonne is sixteen, ingenuous but proud, in the 1940s when she meets Michael, a ‘darkly good-looking’ Greek twice her age. Against the advice of her family, they are soon married and moving north to Cairns from her native Brisbane. He sets her to work in his shop, gambles away their earnings, deprives her of money to buy food for her child, beats her when she protests, wheedles her back with empty promises when she leaves – a litany of awful but familiar horrors. Then the defining act: he wrenches their infant son, Peter, from her arms as she waits in the train that is about to carry her safely away from him and their brutal marriage. His threats cow her into submission: she believes him when he says he will kill both her and Peter if she tries to reclaim him. The official she asks for help suggests the child will be better off without her: ‘after what his father’s done to keep him, he’ll be treated like a prince.’

Peter found his mother thirty-six years later by the simple expedient of searching the official records, and Olsson wrote her half-brother’s story at his request. She catalogues the remorseless horrors of Peter’s childhood: crippling polio, beatings from his father, a cruel, unhappy stepmother. We cannot choose but empathise with this child who is in physical and mental agony, who spends his childhood running away, only to be taken back and abused again, and who finds the children’s home, and even the attentions of a paedophile, immeasurably preferable to his existence at home with his father. We quietly applaud the defiance which prompts Peter to flee from his father and from other unsympathetic authority figures. This flight leads to a life of crime, which at least promises some material security, and autonomy of a kind.

Despite all this, we never get a satisfactory sense of Peter. Olsson alludes to a similar problem when quoting official reports:

Only one document hints at the real child behind the words, his innocence, his fear, his misery – Peter was vulnerable to paedophiles at the time, it says, because he was on the run, in need of shelter, a timid, suggestible boy lacking in self-assertion. But he is nonetheless cheerful, pleasant, and respectful. The language of his official life ducks and weaves as effectively as Peter does around his own pain.

Olsson’s portrayal of her mother, on the other hand, is three-dimensional: we can understand her suffering and her pride, her regrets and her dissatisfaction: her children ‘disappoint her with our deficiencies, marriages that slip through our fingers, poor judgment, arguments, all of it evidence of our frailty, which she has always seen as her own’. A photograph of the mother at twenty-one helps us to visualise her, but this is only part of it. Olsson grew up knowing her mother’s every mood, reacting instinctively to her every look and impatient sigh, while Peter was a stranger until he was near middle age. Add to this, perhaps, the release that comes with death: her mother, dead at sixty-nine from leukaemia, will never read and judge what has been written, while Peter was surely the book’s first and most attentive reader. This could not help but influence any writer, especially one so sensitive to the ethics and difficulties of writing a family memoir like this.

Olsson, a journalist, became aware of these sensitivities as soon as she began the project: ‘After a lifetime of dealing in certainties – the plain facts of journalism, my own black and white views – I began to feel the nausea of uncertainty’ – of conflicting accounts of the past that couldn’t be tidily fact-checked. Most of the chapters are only two or three pages, as if this material is too painful to dwell on. The narrative switches back and forth between her reconstruction of the inner worlds of Yvonne and Peter, with frequent passages of recollection, or reflection, from Olsson herself. Continuity sometimes suffers as a result. For example, Olsson’s father, Yvonne’s second husband, has a son from a previous marriage, Lennart, who visits briefly when Olsson is fourteen. Olsson is smitten by his ‘aquamarine eyes, and … soft, easy manner’. He leaves, never to be mentioned again until we read, ‘I met Lennart’s children and visited his grave in Norway with my father.’ His grave?

These are minor caveats when weighed against the many virtues of this book. Olsson refuses to claim exceptionalism for this story, carefully placing it in the context of the widespread family separations not just condoned but carried out by authorities at the time. And she does not shy from relating with bracing honesty the unhappy sequel to the ‘happy ending’: misunderstanding, estrangement, and bitterness, resolved only after Yvonne’s death.

Boy, Lost is an intelligent and deeply serious book about lives full of pain, but it ends on a note of optimism and reconciliation, as Peter accepts with grace his half-sister’s apology for having the childhood that he missed.

Comments powered by CComment