What was your favourite book of 2019? Read what our critics and writers have to say about this year's finest literary achievements. Ranging across fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, the selection below has plenty to browse through from a year of exemplary writing. Let us know in the comments what you think of the selection, and which books you think were missed!

✦

Felicity Plunkett

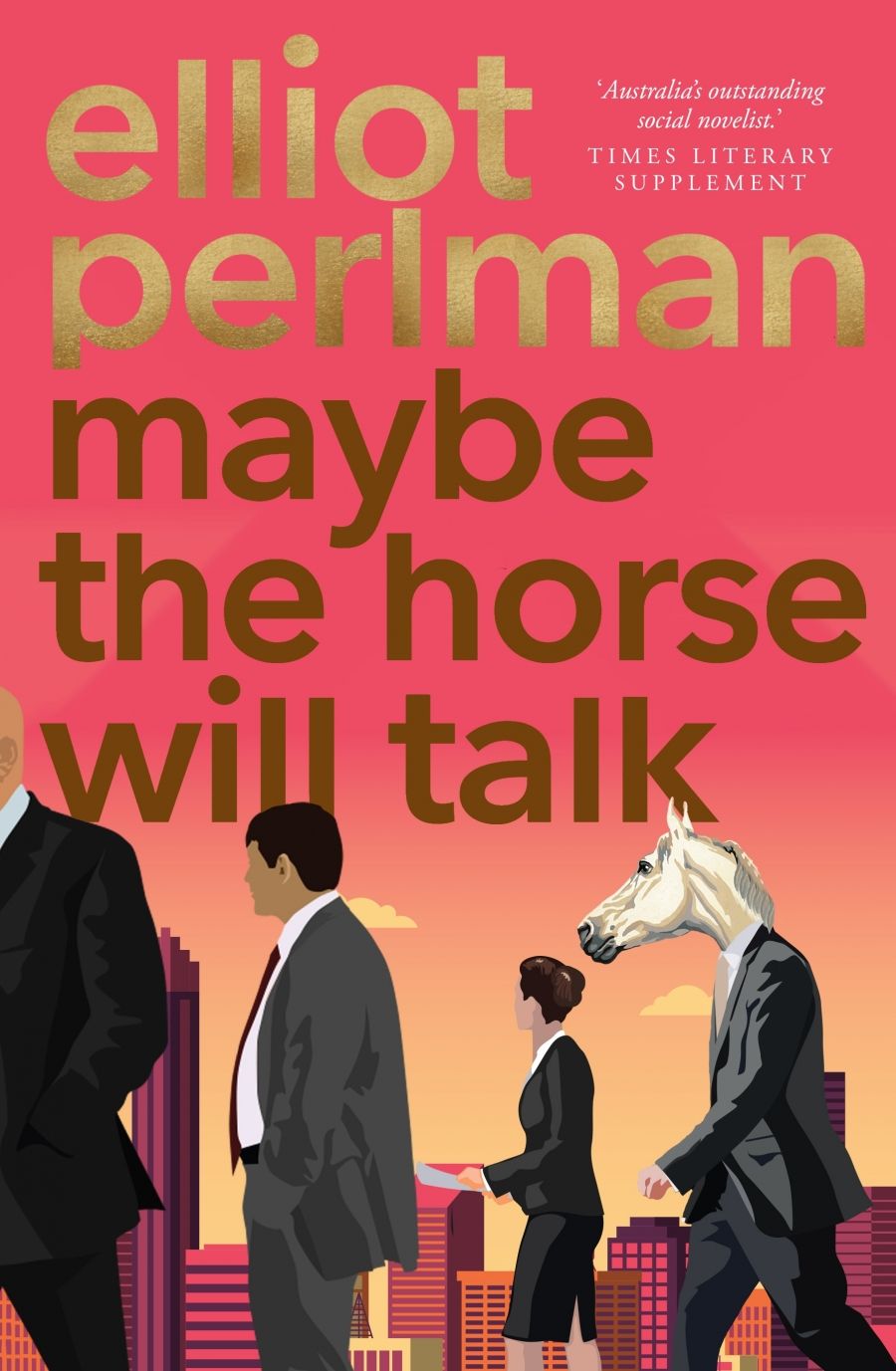

Denise Riley wrote Time Lived, Without Its Flow (Picador) after her son’s death, the lyric slivers of her essay considering atemporality and mourning from the ‘instant enlargement of human sympathy’ she evokes. Charmaine Papertalk Green’s Nganajungu Yagu (Cordite) is a generous work of poetic witness and respect for ancestors, culture, and language inspired by a ‘red journey suitcase’ of letters between the teenage poet and her mother. Michelle de Kretser’s On Shirley Hazzard (Black Inc.) offers a masterclass in reading – Hazzard’s work and beyond. The layers of de Kretser’s exhilarating, writerly rereading collect other people’s observations. It would be difficult to read this wonderful book and not return to (or embark upon) reading Hazzard’s work. I raced through Elliot Perlman’s Maybe the Horse Will Talk (Vintage, 12/19), pausing to admire the meticulous architecture and loping, syncopated pace of its anatomy of corporate greed and human tenacity. Ali Smith’s Spring (Hamish Hamilton, 6/19) continues her urgent, virtuosic, ethical seasonal quartet.

Grace Karskens

Samia Khatun’s Australianama: The South Asian odyssey in Australia (University of Queensland Press), fiercely and beautifully written, signals a breakthrough in Australian history, moving far beyond British colonial frameworks to uncover the powerful histories of the South Asian diaspora in Australia. Khatun’s imaginative narrative moves across time and languages, through places, cultures, and stories. I am enchanted by Favel Parrett’s novel There Was Still Love (Hachette, 11/19), which similarly transports readers into different realms, this time the intimate worlds of children who are loved and cared for by grandparents, no matter the difficult and bewildering world outside, and the sorrows of their lives. Absorbing and moving, it reveals the beauties and comforts of small things. Jasmine Seymour and Leanne Mulgo Watson’s exquisitely illustrated book Cooee Mittigar: A story on Darug Songlines (Magabala Books) introduces children to the Aboriginal stories, images, and language of Darug Country. Children, parents, and grandparents will love this book.

Frank Bongiorno

This year I stuck to my knitting: it was mainly Australian history for me. I was impressed with Marilyn Lake’s Progressive New World: How settler colonialism and transpacific exchange shaped American reform (Harvard University Press, 3/19). Lake covers a period which I thought I knew better than any other, but it was startling to see Australia’s famous legislation of the decades around Federation making its way into United States political debate. Romain Fathi’s Our Corner of the Somme: Australia at Villers-Bretonneux (Cambridge University Press) is a bold account of a long-running case of national narcissism. Dennis Altman’s Unrequited Love: Diary of an accidental activist (Monash University Publishing) seemed to me a beautifully crafted insight into one of the most influential Australians of our times. Michelle Arrow does many intelligent things with a turbulent decade in The Seventies: The personal, the political and the making of modern Australia (NewSouth Publishing, 4/19).

Alice Nelson

‘If the world is torn to pieces,’ writes Terry Tempest Williams, ‘I want to see what story I can find in fragmentation.’ This desire is the animating principle of all my favourite books this year, including Williams’s own hauntingly beautiful Erosion: Essays of undoing (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). The fraught necessity of steering a course between despair and hope is also explored by David Carlin and Nicole Walker, who have collaborated in an exquisitely digressive essay collection in epistolary form called The After-Normal: Brief, alphabetical essays on a changing planet (Rose Metal Press). Tessa Hadley’s incisive and powerful Late in the Day (Jonathan Cape) is about the complex and shifting dynamics of long marriages. A particularly impressive Australian début comes from Bindy Pritchard, with her short story collection Fabulous Lives (Margaret River Press), which contains a fascinating tangle of ideas about loss and reconfiguration, rendered in crystalline prose.

Trent Dalton

I’ve been immersed this year in some excellent non-fiction books by some brilliant Australian journalists. Matthew Condon’s The Night Dragon (UQP, 7/19) explores one of Queensland’s most notorious and calculated underworld killers, and why it took forty years to bring him to justice. Every Australian politician – every Australian, to be sure – needs to read Jess Hill’s See What You Made Me Do: Power, control and domestic abuse (Black Inc., 9/19) if they are serious about addressing our national domestic abuse crisis. Dan Box’s Bowraville (Penguin, 8/19) is a harrowing bookend to the journalist’s relentless investigations into the murders of three Aboriginal children. And I hope Santa’s sack is filled this year with a million copies of David Leser’s Women, Men and the Whole Damn Thing (Allen & Unwin, 9/19) and the big guy drops them down from his sleigh over all of us sunburnt blokes at the cricket.

Billy Griffiths

Underland: A deep time journey (Hamish Hamilton, 10/19) is English nature writer Robert Macfarlane’s most ambitious book to date. It is haunting and urgent and beautifully written. Christina Thompson’s Sea People: The puzzle of Polynesia (William Collins, 6/19) is a lively and lucid journey through Polynesian history, written with respect, wonder, and a keen awareness of the politics of knowledge. I was swept away by Yōko Ogawa’s sinister yet poignant novel The Memory Police (Pantheon, published 1994, translated 2019), an allegory of loss, a meditation on the fragility of inner lives, and a reminder of the profound dangers of historical amnesia. And don’t miss Anna Krien’s first novel, Act of Grace (Black Inc., 10/19). Like her non-fiction, it is brave, bracing, and alert to complex truths.

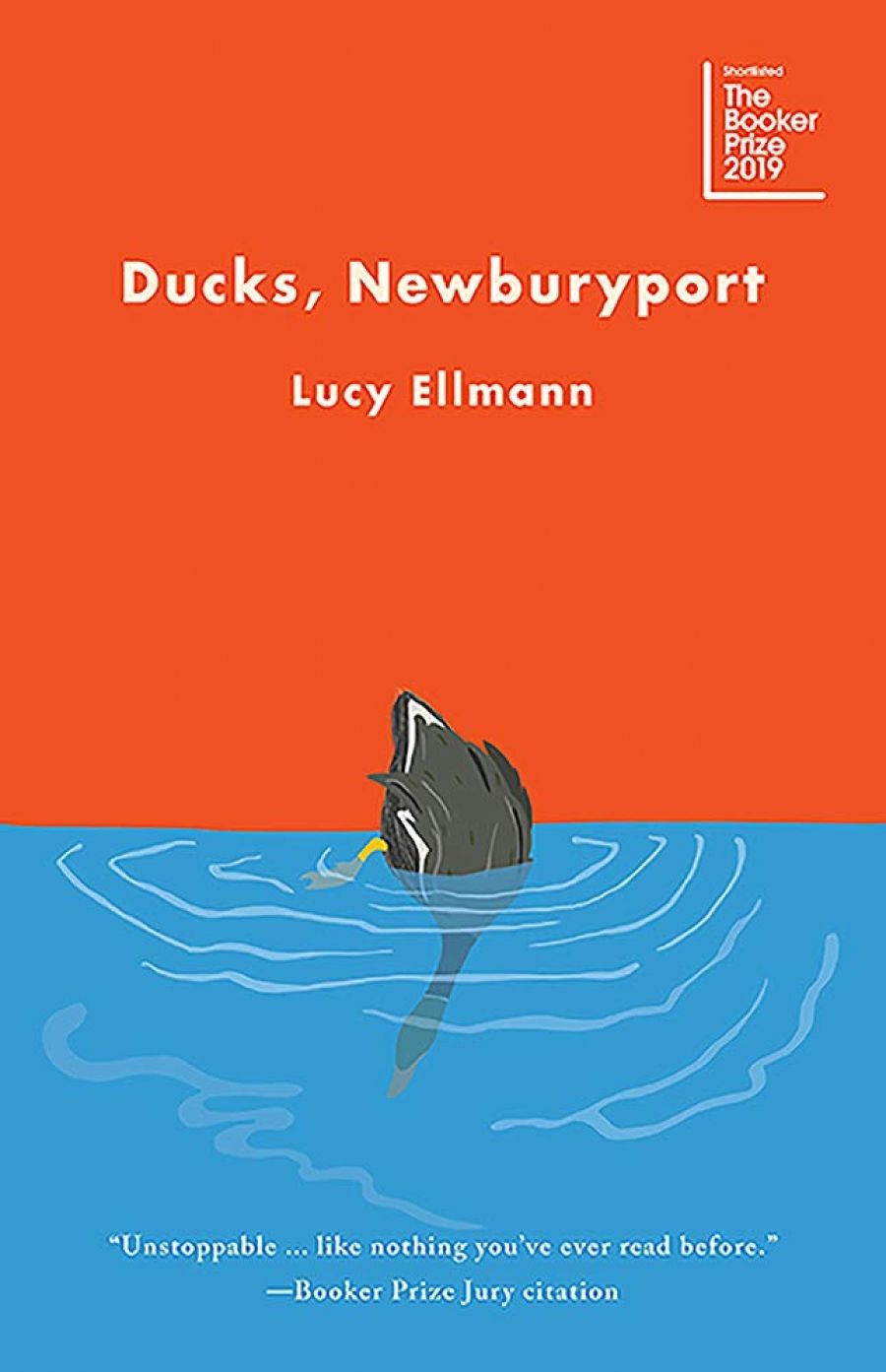

James Ley

This year I am on the bandwagon for Lucy Ellmann’s retro-modernist behemoth Ducks, Newburyport (Text Publishing, 12/19). Yes, it is sprawling and ungainly and more than a little maddening; and yes, it has its longueurs, but its great torrent of associations and its rich humour come closer than anything else to capturing that weird combination of anxiety and inanity that is the hallmark of our troubled times. I also think Luke Carman’s essay collection Intimate Antipathies (Giramondo) hasn’t received the credit it is due, possibly because a few of its more (ahem) controversial inclusions overshadowed the self-deprecation and pathos of its more reflective pieces. But its intimacy is every bit as good as its antipathy. And for anyone interested in a better class of airport novel, I can recommend Andrew McGahan’s The Rich Man’s House (Allen & Unwin, 9/19), a trashy but thoroughly entertaining disaster story about an impossibly tall mountain. The descriptive passages gave me vertigo.

Susan Wyndham

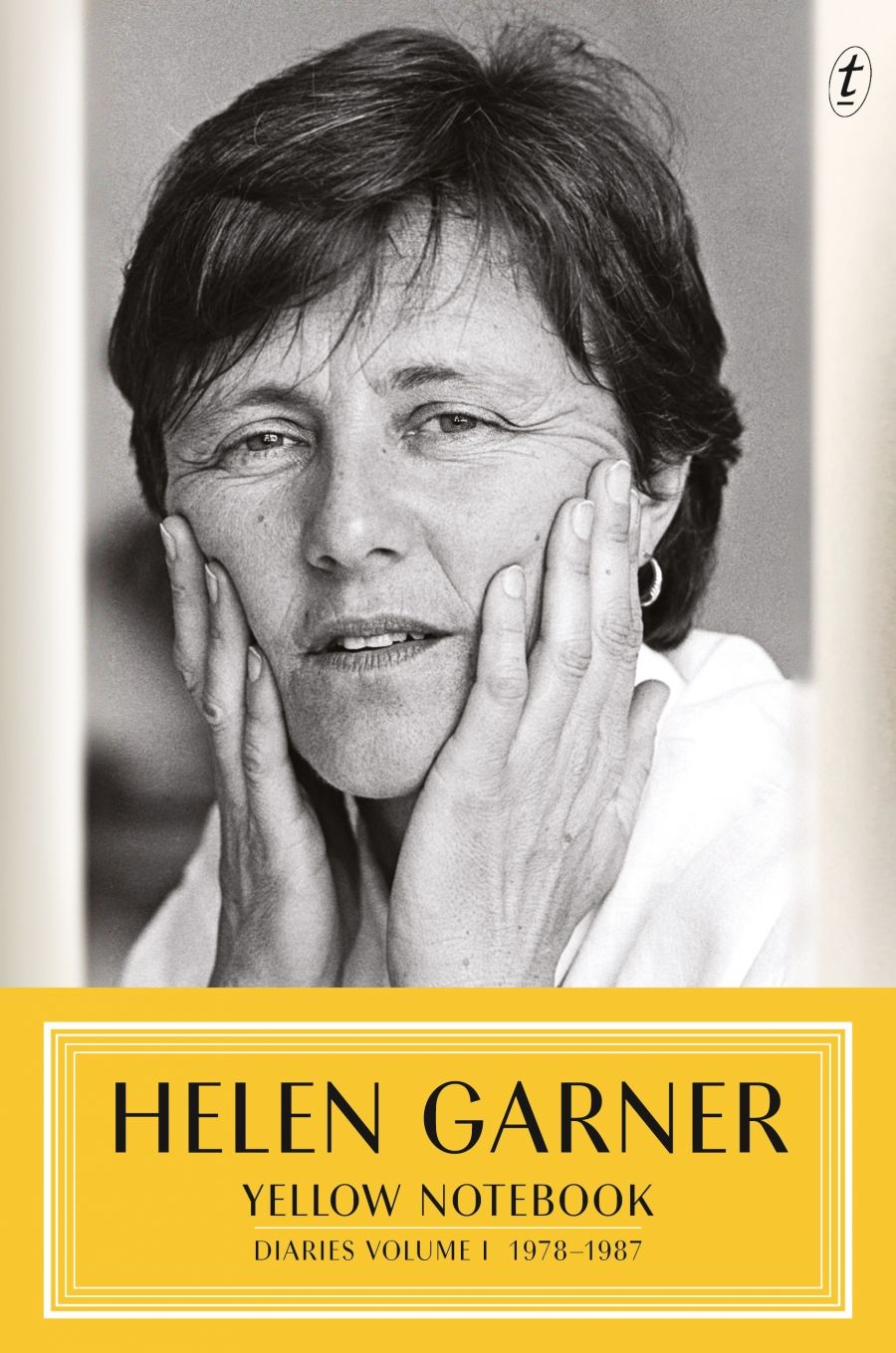

Two novels about American families wowed me. The Dutch House by Ann Patchett (Bloomsbury), made perfect by her narrative skills, follows a brother and sister who spend a lifetime trying to understand their parents. Lucy Treloar creates a disturbing but beautiful sense of place in Wolfe Island (Picador, 9/19) as lapping water and social anarchy force a sculptor out of seclusion. Helen Ennis puts flesh on a fine artist in her biography Olive Cotton: A life in photography (Fourth Estate). Helen Garner’s Yellow Notebook: Diaries Volume 1, 1978–1987 (Text, 12/19) proves she can’t write a bad sentence, even in private.

Brenda Walker

Susan Sontag once described herself as ‘gleaming with survivorship’. Anne Boyer’s The Undying: A meditation on modern illness (Allen Lane) looks at what cancer survival can mean. Her book is not a celebration of personal gleaming; it is a ferocious account of the cost of survival and the use of cancer patients as sentimental emblems of fortitude, or ‘another person’s epiphanies’. On Shirley Hazzard, Michelle de Kretser’s joyous work of appreciation, marks a high point in Black Inc.’s Writers on Writers series. Confident and discriminating, Hazzard is the forebear of many Australian novelists who write with literary poise and a great command of character, including de Kretser and Charlotte Wood. I can’t think of a finer account of Hazzard’s stylistic and political distinctiveness. Tara June Winch’s The Yield (Hamish Hamilton, 8/19) gathers up family, Country, and spirituality, blanketing one part of rural Australia in Indigenous history and language in an impressive rebuking of loss and colonialism.

Beejay Silcox

Cities under cities, Paleolithic art galleries, bronze-age tombs, warehouses of toxic doom, and a forest internet powered by empathetic mushrooms: Robert Macfarlane’s Underland is an awestruck and awestriking catalogue of the world underneath us. ‘To understand light,’ Macfarlane writes, ‘you need first to have been buried in the deep-down dark.’ Here is nature writing at its most exigent and magnificent: equal parts elegy, map, metaphysical disquisition, and exultant sensory surrender. When I finished Underland, it felt like surfacing. I felt the same breathlessness reading Charlotte Wood’s The Weekend (Allen & Unwin, 11/19) a blisteringly intelligent novel about rifts of another sort: the ‘strange caverns of distance’ that are wrenched open in grief. Wood’s new novel of precarious friendships is an elegantly self-contained fury – a thunderstorm in a bottle.

Paul Giles

Ian McEwan’s Machines Like Me (Jonathan Cape, 5/19) weaves his familiar preoccupations – technology, war, politics – into a darkly comic alternative history of Britain and is perhaps the most successful novel he has written. Toni Morrison’s The Source of Self-Regard: Selected essays, speeches, and meditations (Knopf) is an indispensable collection of non-fiction by perhaps the most important writer of our age, addressing topics as varied as opera, time, and memory, as well as issues relating to race. James Simpson’s Permanent Revolution: The Reformation and the illiberal roots of liberalism (Harvard, 7/19) is a revisionist account of the seventeenth-century emergence of liberalism from an Australian scholar in exile, which sheds new light on how evangelical religion continues to shape contemporary politics. And the exhibition catalogue Janet Laurence: After nature, edited by Rachel Kent (Museum of Contemporary Art), offers a handsomely illustrated and informative account of this important Australian visual artist.

Gregory Day

As the various tropes of crisis heighten, I return to strangeness, the strangeness of pre-commodified voices. So this year it was back, or perhaps forward, to Emily Dickinson, and how! Cristanne Miller’s Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As she preserved them (Harvard University Press) is a suitably immense way to experience Dickinson’s ‘pierless bridge’. The product of various championings of the poet’s distinctive methods and voicings down through the years, it reinforces the fact that Dickinson is the nature writer for our histrionic and overmediated times. As someone working the seams of a new novel dealing in realms of early bush media, I also enjoyed Wendy Haslem’s From Melies To New Media: Spectral projections (Intellect Books), which offers a delicate survey of the way the tactilities and textures of analogue days determine so much in our digital present. The chapter on the Tate’s Eadweard Muybridge app, Muybridgizer, is worth the price of admission on its own.

Ali Alizadeh

This was a good year for philosophy, and for horror. My philosophy picks are from the same publisher (Bloomsbury): Marx: An introduction by Michel Henry (trans. Kristin Justaert); and Happiness by Alain Badiou, translated from French by Australia’s own A. J. Bartlett and Justin Clemens. Plenty in both books to prove that Marxism isn’t, and never was, a cold, anti-humanist economistic doctrine. Badiou even has things to say about affect and pleasure! My fiction picks: Paul Tremblay’s Growing Things and Other Stories (Titan Books) shows that he’s a ridiculously talented – and genuinely terrifying – storyteller. C.J. Tudor’s The Taking of Annie Thorne (Michael Joseph) is an addictive fusion of supernatural horror and crime, and indicates that she’s no one-hit wonder.

Fiona Wright

My favourite novels this year were Carrie Tiffany’s taut and haunting Exploded View (Text, 3/19) and Elizabeth Bryer’s wonderfully strange and often enigmatic From Here On, Monsters (Picador, 9/19). I loved two collections of short stories: Josephine Rowe’s masterful Here Until August (Black Inc, 9/19) and Alice Bishop’s A Constant Hum (Text, 11/19), both of which handle their separate griefs with great delicacy and luminosity. In non-fiction, I loved Luke Carman’s Intimate Antipathies for its alternating cheeky wit and devastating heartbreak, and Chris Fleming’s On Drugs (Giramondo, 11/19) for its clear-eyed incisiveness and intellectual curiosity.

John Kinsella

Again, for me, it’s a poetry year. Charmaine Papertalk Green’s Nganajungu Yagu is a living poem-text of affirmation and intense confrontation with injustice (‘Society slavery here’); Omar Sakr’s The Lost Arabs (UQP), of which I wrote in a blog review: ‘This is not an easy journey on which to accompany this remarkable poet, but join him and see how anger can bring compassion, and how compassion can show why there is anger. The Lost Arabs offers ways not only into Sakr’s personal poetics and psyche, but into a polyphonous sense of community and communities’; Lisa Gorton’s conceptual-textual activism in Empirical (Giramondo, 10/19), with its layered questions of agency, legacy, historical residues, and invasiveness. Like nothing else, not even his previous works, is J.H. Prynne’s large-format, red-ink print Of Better Scrap (Face Press). With conversations happening between poetry books on my desk, a revered Samuel Taylor Coleridge speaks from Gorton to Prynne and back again. Prynne’s poem ‘Familiar Left Hand’ begins: ‘Frost at noon, singular and fragile assign rapier point / aftermath as well indent’, and its lyric-political intensity lifts only as lightning can ‘lift’ nature. Of Better Scrap has poems of insect-close intensity.

Jacqueline Kent

Bill Goldstein’s The World Broke in Two (Bloomsbury Circus) is a brilliantly constructed, imaginative collective biography of Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot, D.H. Lawrence, and E.M. Forster in 1922, when they were writing their most celebrated novels. Robert A. Caro’s Working: Researching, interviewing, writing (Bodley Head) balances the importance of research, intuition, and knowledge of human nature in essays that form a masterclass in the art of life writing. Andrea Goldmith’s Invented Lives (Scribe, 4/19) is a novel of exemplary clarity and insight examining questions of exile, belonging, and history.

Lisa Gorton

Written in the voice of Alan Turing, Will Eaves’s novel Murmur (Canongate) is simultaneously trance-like and analytical, and brilliantly free in its exploration of consciousness and artificial intelligence. I loved Evelyn Araluen’s piece in the Sydney Review of Books, ‘Snugglepot and Cuddlepie in the Ghost Gum’ (11 February 2019), so wildly clever that it reminded me of Italo Calvino’s way of turning the mind inside-out and back again. I found Xia Jia’s short works of science fiction strange and memorable, dream-like satires on technology’s new empire (in translation online at Clarkesworld Magazine). And I’m already rereading Jessica L. Wilkinson’s Music Made Visible (Vagabond), a poetic biography of George Balanchine. Closely researched, the work of years, its poems are all in movement, sudden, and vital.

Andrea Goldsmith

Miriam Sved’s second novel, A Universe of Sufficient Size (Picador, 4/19), is a superbly structured novel of family, history, secrets, trauma, and mathematics, stretching from 1930s Budapest to Sydney in the 2000s. Very impressive. Deborah Lipstadt is a fearless and free-ranging intellectual. Her latest, Antisemitism: Here and now (Scribe, 8/19), is an accessible, punchy account of anti-Semitism, filled with relevant historical perspectives. It is also a practical book, supplying numerous strategies and techniques to use with a wide range of bigots. My highlight of the year is All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking solace in Virginia Woolf (Atlantic Books, 11/19) by Katharine Smyth. This book combines childhood memoir with grief over a beloved and deeply flawed father, difficulties with a very much alive and misunderstood mother, and the power and intimacy of reading. It’s a personal book with a far reach, and I loved it. Imagine a young Susan Sontag, with the welcome addition of humour. Millennial essayist Jia Tolentino, in Trick Mirror: Reflections on self-delusion (Fourth Estate, 8/19), writes like a hand-crafted speedboat, drawing on the likes of Erving Goffman, C.S. Lewis, and DJ Screw as she guides you through the contemporary cultural swamp.

Astrid Edwards

This was a banner year for Australian women writers. Anna Krien’s Act of Grace is a masterpiece. Rarely does a writer’s first move from non-fiction to fiction display such heart and literary craft. Claire G. Coleman continues to entertain (and educate) us with The Old Lie (Hachette, 9/19), reinvigorating Australian speculative fiction in the process. Her reinterpretation of Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum est’ is haunting. Alice Bishop may be the début writer of the year with A Constant Hum, a collection of short fiction about the 2009 Black Saturday fires. No list would be complete without non-fiction. Jess Hill’s See What You Made Me Do should be compulsory reading for all.

Chris Flynn

My number one pick for 2019 goes to City of Girls (Bloomsbury), Elizabeth Gilbert’s ode to joy. Set in the 1940s New York theatre scene, costumier Vivian Morris indulges in sex, booze, and dancing without the usual boring patriarchal consequences. It is a refreshing literary gin fizz, and an antidote to the seemingly endless cavalcade of misery fiction. The Aussie poke in the eye this year comes from Tony Birch. The White Girl (UQP, 8/19) deals with the Stolen Generation and white Australia’s messed-up attitude towards its Indigenous people, with Birch’s trademark humour and grace. Is it tempting fate to call this one next year’s Miles Franklin winner?

Brenda Niall

Don’t mistake Helen Garner’s Yellow Notebook: Diaries Volume 1, 1978–1987 for ‘something sensational to read in the train’, as an Oscar Wilde heroine characterised her own diaries. Garner’s are spare, quiet, reflective: a portrait of the artist and her world, observed with scrupulous honesty. The identities of others are so carefully protected that only insiders will try guessing who is who. Another distinctive voice comes from the reclusive artist Ian Fairweather. Letters from his Bribie Island retreat, with their total concentration on the essential act of painting, are quirky, opinionated, dedicated. Ian Fairweather: A life in letters (Text, 11/19) is superbly edited by Claire Roberts and John Thompson, and generously produced. Kathy O’Shaughnessy’s In Love with George Eliot (Scribe) is a riveting novel underpinned by impressive scholarly work. And welcome back Kate Atkinson and her grumpy sleuth Jackson Brodie in Big Sky (Doubleday).

John Hawke

Australian poetry titles are represented only fleetingly (if at all) in bookshops, so it is necessary to check the websites of leading independent publishers, such as Giramondo, Vagabond, Cordite, and Puncher & Wattmann, for the range of current practice. The outstanding book this year was funded through the goodwill of subscribers, and the generous work of its publisher, Alan Wearne, and its editor, Judith Beveridge. Robert Harris’s The Gang of One (Grand Parade Poets, 8/19) is an authoritative selection of work from one of the most important poets of his generation, and appears a quarter of a century after his death. Melbourne poet π.O. has produced another major collection: Heide (Giramondo), 600-page documentary poem, is a critical survey of Australian cultural history, focusing on the local reception of modernism in art and poetry. This documentary approach is also evident in recent volumes by Lisa Gorton, Natalie Harkin, and Jessica L. Wilkinson, though in each case with distinctive results.

Kieran Pender

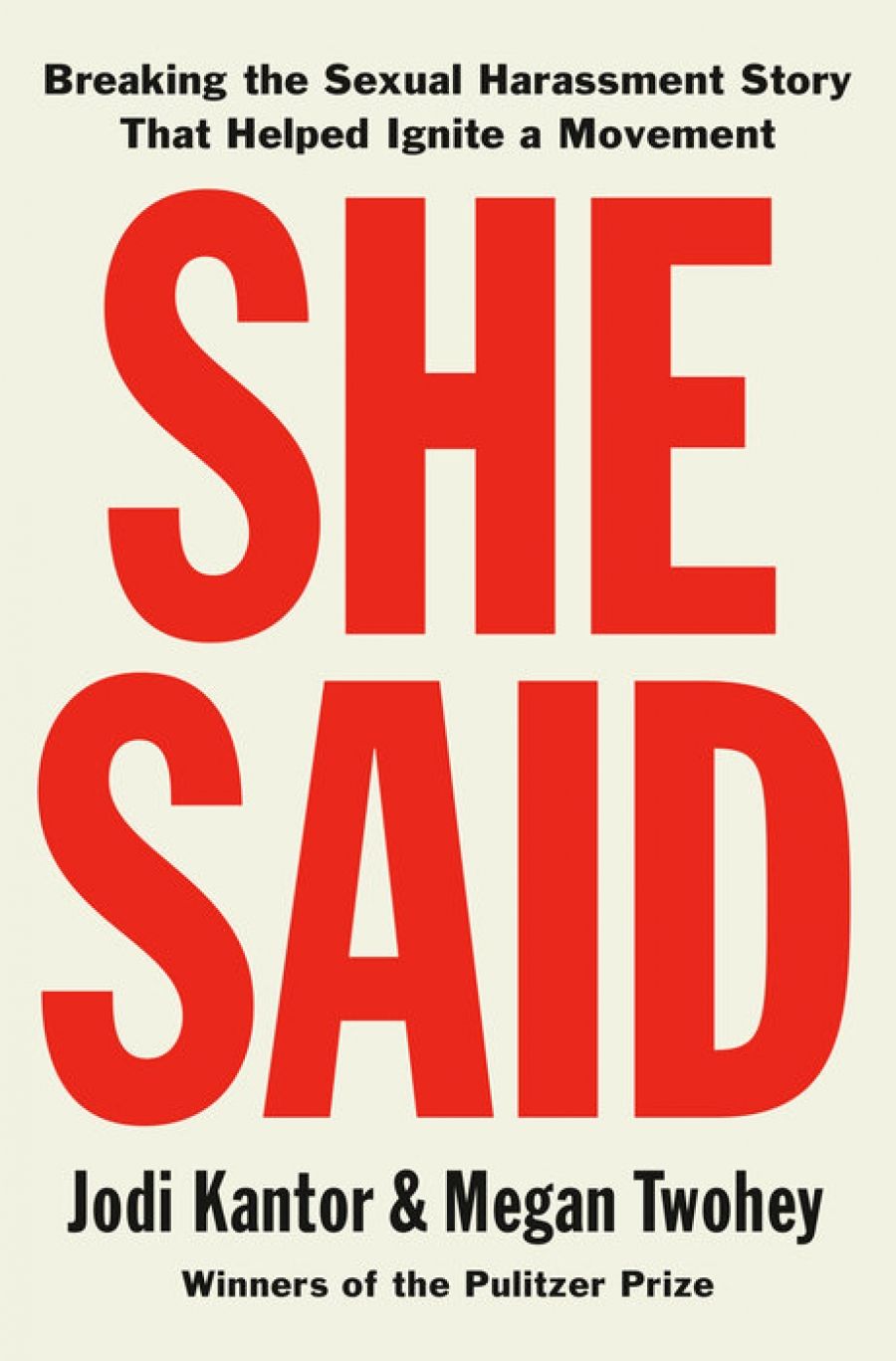

Since The New York Times published allegations of sexual harassment against Harvey Weinstein, the #MeToo movement has reverberated across the globe. The impact continues to be felt in 2019, and has given rise to several compelling books. In She Said: Breaking the sexual harassment story that helped ignite a movement (Bloomsbury Circus, 12/19), Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey – among the reporters who earned a Pulitzer for the Weinstein reporting – provide a gripping consideration of the past, present, and future of #MeToo. Australian David Leser in Women, Men and the Whole Damn Thing offers a male perspective on the persistence of misogyny, discrimination and harassment in society. This was risky – his own daughter told him ‘it’s time for men to shut up and listen’ – but Leser’s honest reflections resonate. Both books remind us of the long road ahead for those seeking a gender-equal world.

Ellen van Neerven

My books of the year include the stunning Nganajungu Yagu by Charmaine Papertalk Green. Charmaine is from the Wajarri, Badimaya, and Southern Yamaji peoples of Western Australia, and the bilingual Nganajungu Yagu springboards from the letters Charmaine and her mother exchanged in 1978–79 when she was living away in Perth for school. This collection reminds me of the close relationship I have with my mother and other older women in my family, as does The White Girl by Tony Birch, which introduces us to one of my favourite characters in recent Australian writing: Odette, proud grandmother to Sissy. Odette is a protector, creator, and nurturer against the rough backdrop of a rural town in the assimilation era. Birch’s touching narrative had me bawling.

Glyn Davis

The Breeding Season by Amanda Niehaus (Allen & Unwin, 10/19) is an assured first novel, testing human relationships against biological fieldwork. The story of Elise and Dan is both a ballet of ideas and carefully signalled drama. Science makes us look at the world anew in Donald D. Hoffman’s The Case Against Reality: Why evolution hid the truth from our eyes (W.W. Norton & Company), which offers a startling thesis that consciousness does not map reality but invents it. He turns the hard problem on its head: how does consciousness create a physical reality? A troubled mind, and delusions that can run through our actions and memories, is the theme of The Hilton Bombing: Evan Pederick and the Ananda Marga (Melbourne University Press, 12/19). Imre Salusinszky interviewed the Hilton bomber over seven years, and presents his story with sympathy, but also a sense of gaps and confusions. The work recalls passions and controversy from an earlier generation in well-crafted prose that moves across decades.

Marilyn Lake

More than thirty years have passed since feminist historians first insisted on the gendered nature of political power. This year a new crop of political histories illuminates this insight from new angles. In The Blackburns: Private lives, public ambitions (Melbourne University Press, 4/19), Carolyn Rasmussen shows how a joint study of the intertwining romantic and political passions of Maurice and Doris Blackburn gives us a fresh perspective on Victoria’s distinctively progressive political culture in the early twentieth century. Michelle Arrow’s The Seventies has at its heart an investigation into the Royal Commission on Human Relationships, created by the Whitlam government, whose radical initiatives led to long-term social (if not political) transformation. In her splendid biography of the path-breaking South Australian premier, Don Dunstan: The visionary politician who changed Australia (Allen & Unwin, 10/19), Angela Woollacott confirms that even as politics remained a masculine pursuit, gender relations were changing.

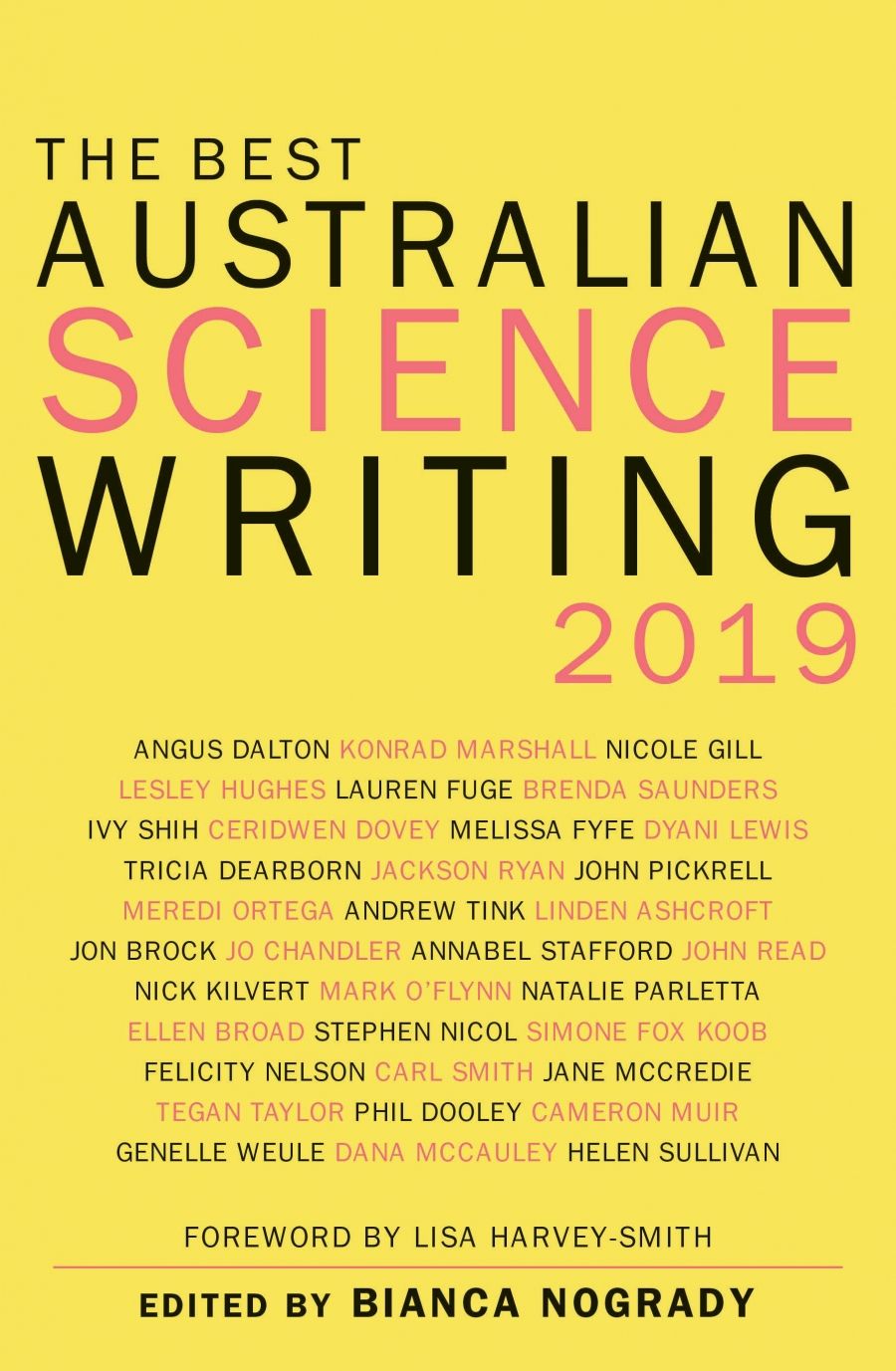

Ceridwen Dovey

Alice Gorman’s Dr Space Junk vs the Universe (NewSouth) passionately describes the material culture of outer space, and reclaims space as a cultural landscape, not as a blank canvas onto which we can project whatever techno-utopian fantasies we like. Gorman, a founder of space archaeology, has a gift for making space feel accessible to ordinary outsiders – showing it’s not just the realm of sci-fi geeks and rocket fanatics. Nicola Redhouse’s Unlike the Heart: A memoir of brain and mind (UQP) is a wise, elegant book about so much more than mothering. Redhouse is unafraid to dive right into psychoanalytic theory and the complexities of neuroscience, weaving these bodies of knowledge into more personal reflections on the post-natal body, mind, and brain. And finally, I greedily read and loved both Nam Le’s On David Malouf (Black Inc., 5/19) and Michelle de Kretser’s On Shirley Hazzard.

Bronwyn Lea

I was surprised that so many books I loved this year were actually published in 2018 and therefore ineligible. But three 2019 titles leap out: Carrie Tiffany’s Exploded View is a dark coal of a novel compressed into a diamond; Josephine Rowe’s Here Until August marks her as one of the best short story writers going; and Emma Lew’s potent Crow College: New and selected poems (Giramondo, 5/19) continues to disturb my waking dreams.

Zora Simic

This year I decided to track my reading on Instagram. My one rule was to post an image and write a short review as soon as I finished, keeping it fresh. Looking back, I’d revise at least half of my hot takes. The ones that have stayed with me, in the order in which I read them, are The Bridge (Scribe, 6/18) by Enza Gandolfo (sad and beautiful), Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend from Little, Brown (wise), Luke Carman’s Intimate Antipathies (for the essay set in the waiting room of a medical centre), The White Girl by Tony Birch (his best yet), Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner from Wildfire (funny and worthy of the hype), and (for sheer audacity) Peter Polites’s The Pillars (Hachette, 9/19). Most of those are novels, but if I had to pick one book of the year it would be non-fiction – Jess Hill’s powerful See What You Made Me Do. She has such respect for the stories of women and children who have endured domestic abuse. Is it too much to hope that Pauline Hanson and Kevin Andrews read it before the forthcoming federal government inquiry into the family law system they will be running?

Kerryn Goldsworthy

Angela Woollacott’s Don Dunstan: The visionary politician who changed Australia is the first full biography of Dunstan, himself such a complex and brightly coloured figure that Woollacott’s scholarly, detailed, emotionally neutral approach nicely balances her material. She steers a steady course between hagiography and its opposite, giving a warts-and-all yet unsensationalised and affectionate account of Dunstan’s style, his personal life, his true political and social vision of an ideal state, and his unique achievements in government. The Weekend is Charlotte Wood’s intensely engaging novel about friendship and grief, exploring the harsh terrain of old age in women’s lives. It doesn’t flinch from the humiliations of the ageing body, from the sadness of inevitable loss, or from the revelations that can shed unwelcome light on the past. Wood’s frank but generous view embraces the full range of this experience, all the way from scenes of utter devastation to moments of laugh-out-loud comedy.

Geraldine Doogue

Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universe (Fourth Estate) is a triumph. Its crackling energy and sheer heart consumed me. Can it really be a first novel, with that level of proficiency and galloping pace? Yes, the plot becomes somewhat fantastical towards the end, but I was transfixed, especially by the Brisbane newsroom scenes, surely some of the best-ever depictions of the vulgar, idealistic, aspirational mix that characterises a good news hub. I would almost read Howard Jacobson’s letter to his dog, such is my devotion to his humour, his generosity to characters. Live a Little (Jonathan Cape) may not be a vital read, but it is replete with Jacobson’s conviction that no one is beyond redemption. L’chaim! Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is in Trouble – a tale of the moment – relentlessly mines modern Manhattanites’ search for meaning and the elusive life of good values. Exhausting, neurotically sexy, and somehow cautionary.

Paul Kildea

I’m currently halfway through Orlando Figes’s intriguing account of the phenomenal soprano Pauline Viardot, her husband, Louis, and her lover, Ivan Turgenev. The Europeans: Three lives and the making of a cosmopolitan culture (Allen Lane) is far more than a biography, however: Figes places these three smack-bang in the centre of the huge shifts in European culture brought about by railways, industrialisation, and national unification. Some years back Willem de Vries wrote a vitally important book about the Nazi looting of Jewish music collections. It has now been translated into French – Commando Musik: Comment les nazis ont spolié l’Europe musicale (Buchet Chastel) – and launched in France, the country that suffered so grievously in this regard. He’s a friend, which is why I’m thrilled Dennis Altman has written such a good book. Unrequited Love: Diary of an accidental activist is part memoir, part explanation for Altman’s failed love affair with the United States, with some fabulous cameos.

Gideon Haigh

Best non-fiction: Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing: A true story of murder and memory in Northern Ireland (Doubleday), a melancholy retelling of the Troubles and their remembering. Best fiction: the Vintage reprint of Butcher’s Crossing, John Williams’s 1960 novel of the American frontier, big, bold, and bloody, like a prose Deadwood, and a less baroque Cormac McCarthy.

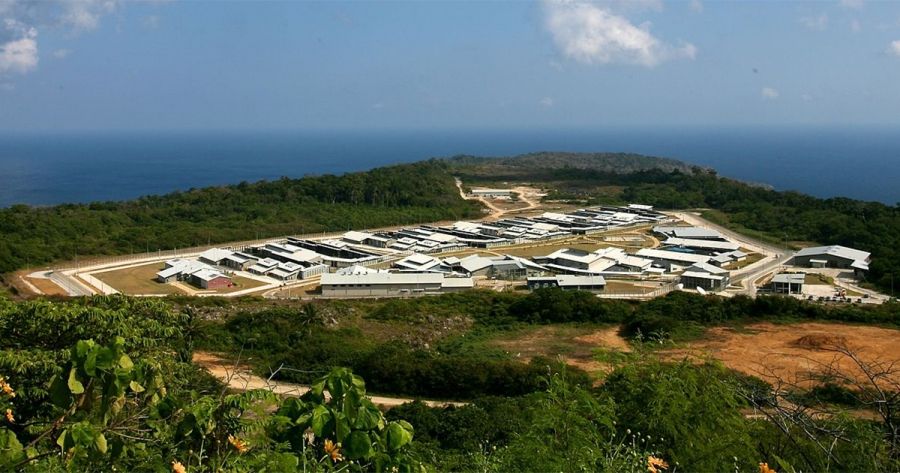

Hessom RavaziHessom Razavi is the recipient of the ABR Behrouz Boochani Fellowship. The Fellowship, worth $10,000, honours the artistry and moral leadership of Behrouz Boochani, the award-winning author of No Friend But the Mountains (2018), who has been imprisoned on Manus Island since 2013 and is now in New Zealand on a temporary visa. Dr Razavi will make a significant contribution to the magazine in 2020 with a series of substantial articles on refugees, statelessness, and human rights. He was chosen from an impressive international field.

Hessom RavaziHessom Razavi is the recipient of the ABR Behrouz Boochani Fellowship. The Fellowship, worth $10,000, honours the artistry and moral leadership of Behrouz Boochani, the award-winning author of No Friend But the Mountains (2018), who has been imprisoned on Manus Island since 2013 and is now in New Zealand on a temporary visa. Dr Razavi will make a significant contribution to the magazine in 2020 with a series of substantial articles on refugees, statelessness, and human rights. He was chosen from an impressive international field.

.jpg)