- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Language

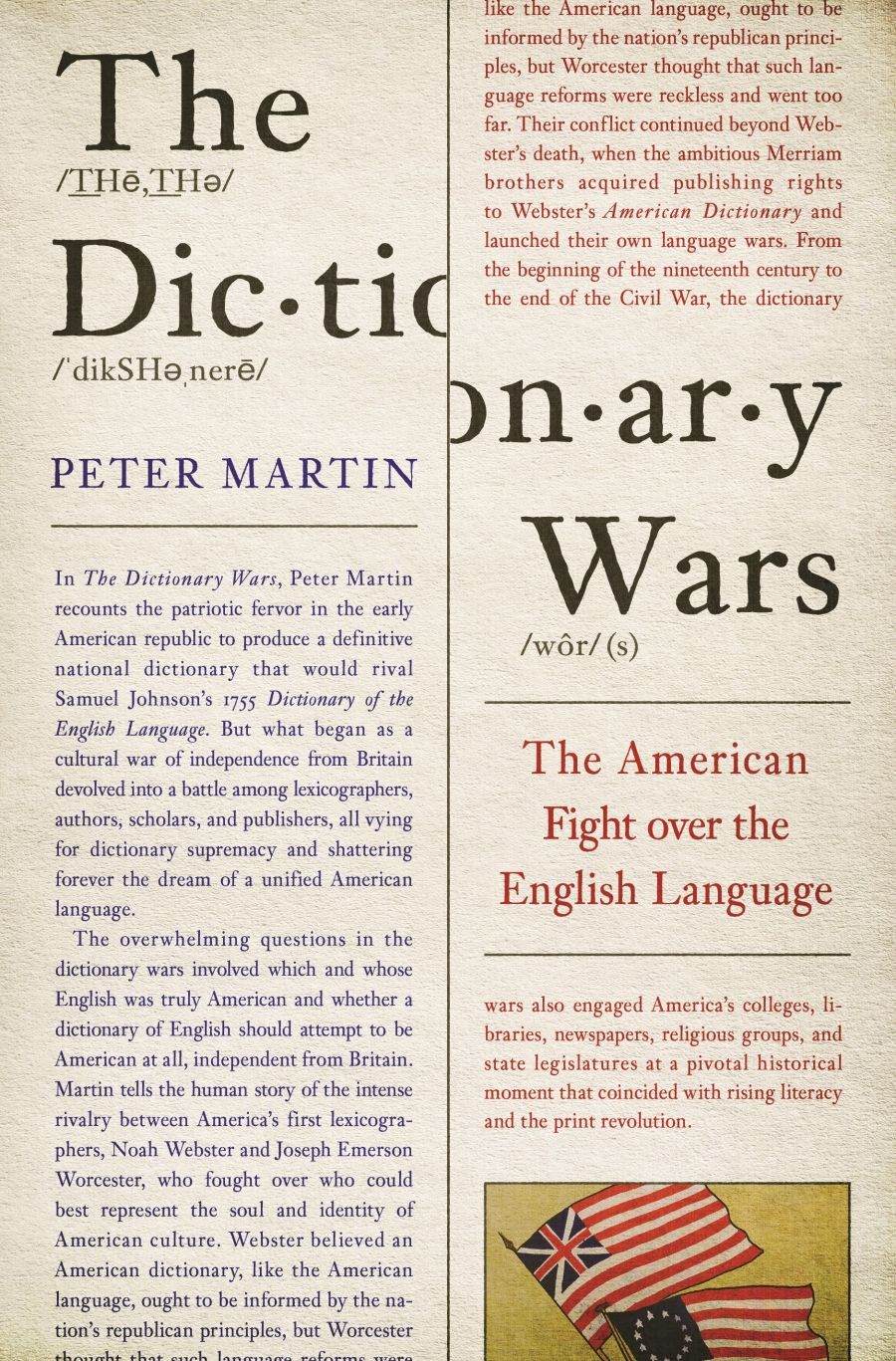

- Custom Article Title: Bruce Moore reviews 'The Dictionary Wars: The American fight over the English language' by Peter Martin

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title of this book refers to the battle for market dominance between the editors and publishers of two rival dictionaries, the one edited by Noah Webster and the other by Joseph Worcester. This battle took place largely between 1829 and 1864, and it was played out in the newspapers and by means of pamphlet warfare ...

- Book 1 Title: The Dictionary Wars

- Book 1 Subtitle: The American fight over the English language

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint), $43 hb, 368 pp, 9780691188911

An American dictionary became a necessary part of this linguistic and cultural revolution, but it was not until 1828 that Webster produced his major dictionary. Along the way, he converted to Calvinism, spent ten years pursuing some outdated theories of etymology, and developed some fairly cranky ideas about the reform of spelling and orthography. Some of the reforms introduced in this dictionary stuck, and we would all recognise them as distinctive features of American English, such as the change from -re to -er at the end of words such as metre and theatre or the absence of consonant doubling in the past tense of some verbs (traveled for travelled). But other proposed reforms such as aker for acre, porpess for porpoise, tung for tongue, and numerous others, did not survive.

In 1829 an abridged version of the dictionary was produced by the publisher Sherman Converse. He organised editorial assistance from the young scholar and lexicographer Joseph Worcester and from Webster’s son-in-law Chauncey Goodrich, professor of rhetoric at Yale. Through a series of manoeuvres, Webster was sidelined from most of the editorial process, enabling the editors to correct many of his weaknesses in spelling and orthography, pronunciation, and etymology, and reducing the length of some of the long-winded definitions that often had a heavy Christian emphasis. Thus began the dictionary version of the Civil War that would later break out into a series of skirmishes between American lexicographers, scholars, universities, families, and publishers.

Joseph Worcester is not well known now, but he was in every way superior to Webster as lexicographer and scholar. Webster was angry with what Worcester and Goodrich had done in the abridged version, but he was even angrier when Worcester produced his own rival dictionary in 1830. Webster accused Worcester of plagiarising material from the 1829 abridged version that he had worked on. Accusatory pamphlets were flung about on both sides. Peter Martin shows us that Webster’s charges were nonsense.

Webster died in 1843 (‘clutching a copy of his speller’, Martin tells us), and through a complex series of legal and financial events the control of the dictionary eventually came into the hands of the publishers George and Charles Merriam. Worcester continued to produce dictionaries that were well reviewed, and the Merriams saw Worcester as the greatest threat to the success of their Webster’s dictionary. The second greatest were the Websterian weaknesses that were still in the dictionary. To solve the first threat, the Merriams embarked on a campaign of denigration and vilification of Worcester and his dictionaries: more pamphlet warfare, the ‘planting’ of newspaper articles, and the generation of ‘scholarly’ articles by mercenary academics. To solve the second, they continued the process of de-Websterising Webster’s lexicography. At the same time, however, they encouraged the canonisation of Webster himself as the great linguistic nationalist and teacher of the nation.

Entrepreneurship (we might now call it ‘fake news’) triumphed over truth. The Merriams won, and Webster’s became the standard American dictionary. Its influence is evident in the fact that James Murray and Oxford University Press kept it closely in mind when making decisions about the length and extent of the OED.

Ironically, the Merriams were too successful, since the courts eventually decided that ‘Webster’ had become a generic name for ‘dictionary’, and that any publisher could include the term ‘Webster’ in the name of any dictionary. You’ve probably got a ‘Webster’ on your shelf – take a squiz at its publishing details!

There were no comparable dictionary wars in Britain, although the editors of the OED certainly had their battles with the Oxford syndics. In Australia we had a mini-war between the Macquarie group with their Webster-like nationalism and the group led by Bill Ramson that produced the Australian National Dictionary (modelled on the OED). In an account of this skirmish in his book Lexical Images (2002), Ramson describes the fourteen-page telex from the Macquarie Library’s Kevin Weldon, railing against the decision to offer the publishing rights of the Australian National Dictionary to OUP, as ‘a uniquely Australian document’.

But Australian telex warfare is no match for the virulent publishing warfare that dominated American lexicography in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Dictionary Wars is a fascinating account of these battles, and gives appropriate attention to Joseph Worcester, the greatest casualty of the conflict.

Comments powered by CComment