- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

When it comes to serial muses, Alma Maria Schindler Mahler Gropius Werfel was in a class of her own. Lou Andreas-Salomé may have included Friedrich Nietzsche, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Sigmund Freud among her conquests, and Caroline Blackwood scored Lucian Freud, Robert Silvers, and Robert Lowell, but Alma’s conquests were more and varied. Antonia Fraser is supposed to have claimed that she ‘only slept with the first eleven’; although Alma would not have understood the reference, she would have agreed wholeheartedly with the concept. Gustav Klimt, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Gustav Mahler, Oskar Kokoschka, and Walter Gropius were major notches on her belt, and if the reputations of the author Franz Werfel and the political theologian Johannes Hollnsteiner have faded, they were big in their time.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

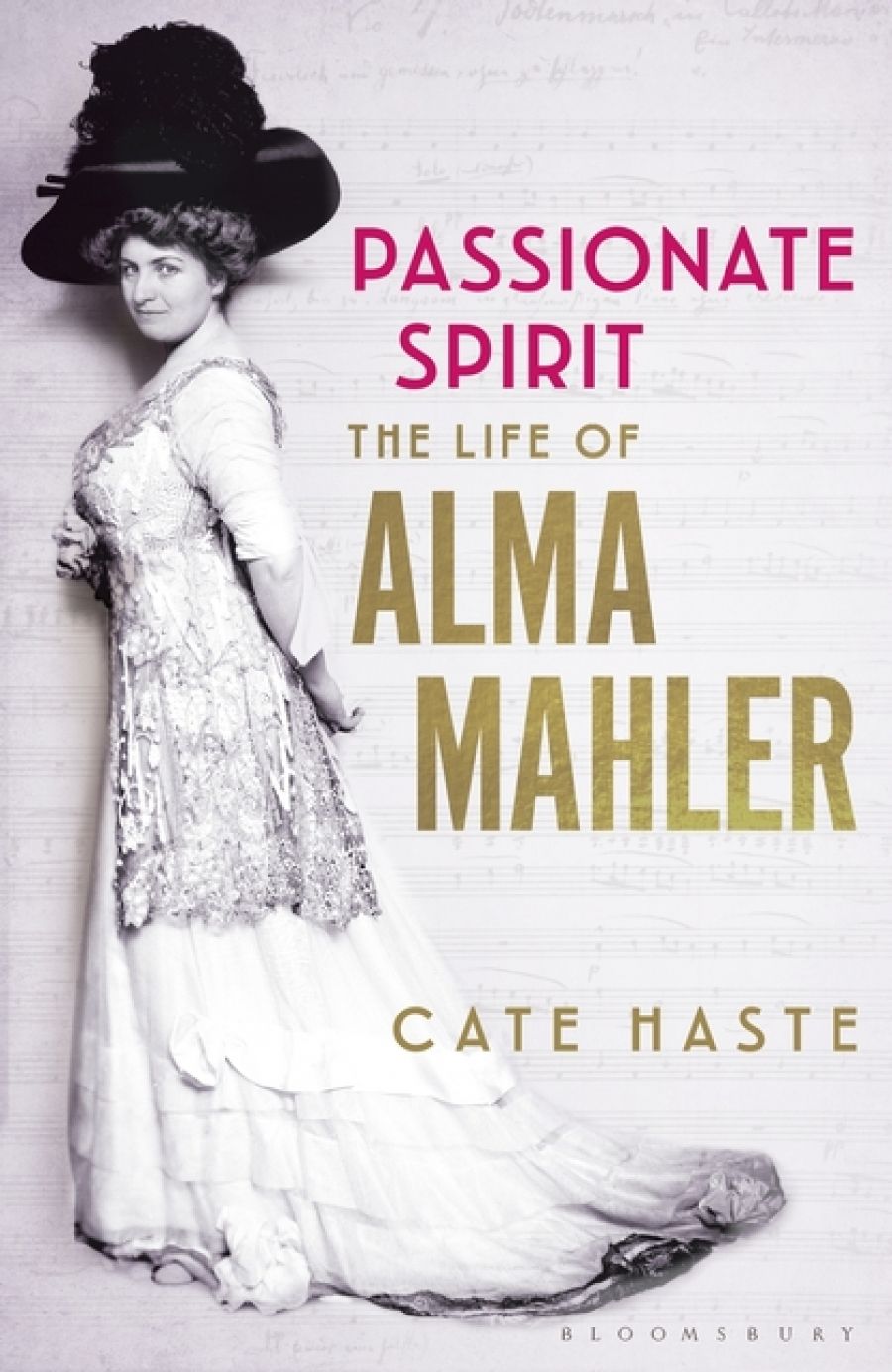

- Book 1 Title: Passionate Spirit

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of Alma Mahler

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $44.99 hb, 469 pp, 9781408878323

Reactions to this Viennese Circe have always been definitely pro or con. Elias Canetti wrote a withering description of Mahler as ‘a large woman overflowing in all directions, with a sickly-sweet smile’ who asked him: ‘Did you ever see Gropius? A big handsome man. The true Aryan type. The only man who was racially suited to me. All the others were little Jews. Like Mahler.’ To Ernst Krenek, she had ‘the knack of turning life into a dizzying carousel’. She reminded him of ‘an extravagantly festooned battleship … Wagner’s Brünnhilde transposed to the atmosphere of Die Fledermaus’. On the other hand, Thomas Mann found her amusing. She was one of the few who could pacify the demanding Hans Pfitzner, and the reserved Otto Klemperer, bipolar before such a condition had been defined, opened up to her about his depressions and found her understanding and supportive. The same divergence of opinion applies to her biographers. Among recent biographies, Oliver Hilmes leads the prosecution with his book Malevolent Muse (2015). Now Cate Haste comes to the rescue with Passionate Spirit.

Alma Mahler-Werfel née Schindler, 1899 or earlier (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Alma Mahler-Werfel née Schindler, 1899 or earlier (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Alma Maria Schindler was born in Vienna in 1879. Her father, Emil Jakob Schindler, was a fashionable landscape painter admired by the Austrian Crown Prince Rudolf among others. Although he died when she was only thirteen, she idolised him all her life. ‘I am the daughter of an artistic tradition,’ she grandly proclaimed in one of her notoriously self-serving and unreliable memoirs. Her stepfather, Carl Moll, was a co-founder of the Vienna Secession movement, and Alma grew up surrounded by the cream of creative Vienna. From an early age, she showed musical talent both as a pianist and as a composer. The promising young composer Alexander von Zemlinsky thought enough of her songs to agree to take her on as a student; from this developed a rather tempestuous amitié amoureuse, which foundered when Gustav Mahler, Vienna’s musical master, took an interest in the attractive and vital young woman.

‘I am not a Gropius and so I cannot call myself Gropius either. My name is Mahler for all eternity,’ Alma wrote to her second husband, Walter Gropius, as their doomed marriage disintegrated. It is her carefully constructed and much contested narrative of the nine years she spent with the composer that has kept her reputation alive. It was difficult for the vibrant young woman to learn to play second fiddle, and much has been made of Gustav’s insistence that she stop composing, but the claims that he thereby destroyed a major career are spurious. Towards the end of his life, Gustav began to encourage her to write more lieder, and when he died she was only thirty-one and could easily have taken up composition again. In a moment of clear-sighted honesty, she wrote, ‘I don’t lack talent, but my attitude is too frivolous for my objectives, for artistic achievement.’

Depending on one’s attitude to Alma, her passionate affair with the handsome, virile young architect Walter Gropius, which took place while she was still married to Mahler, was either the rebellion of an unsatisfied, taken-for-granted wife or the underhand selfish betrayal of a faithful, affectionate husband, a betrayal that shortened his life. Certainly, it set up a pattern in which Alma moved on to the next affair before she had entirely finished with the previous one.

After Gustav’s death, Alma kept Gropius dangling while she embarked on a feverish, SM-flavoured relationship with Oskar Kokoschka. Although Alma eventually put an end to their affair, their sexual rapport lasted all their lives. The abandoned, in both senses of the word, Kokoschka ordered from the dollmaker Hermine Moos a life-size replica of Alma with the instructions: ‘please make it possible that my sense of touch will be able to take pleasure in those parts where the layers of fat and muscle suddenly give way to a sinuous covering of skin’. Even though the delivered doll was a great disappointment, Kokoschka kept fantasising along the same lines. Decades later, he writes to the then-septuagenarian Alma promising to make her ‘a life-sized wooden figure of myself’ that ‘should have a member in the position you made it for me’ – a proposition that gives new meaning to the phrase ‘morning wood’.

World War I added a further layer of complexity to their tangled relationships. Both men signed up and suffered mental and, in Kokoschka’s case, physical injury. Alma’s petulant letters to them show an appalling lack of awareness. When mistaken reports of Kokoschka’s death reached Vienna, instead of grieving, the ever-resourceful Alma gained access to his atelier, removed her incriminating letters, and snaffled a few sketches as well.

Alma’s marriage to Gropius was over almost before it had begun; by then she had met the man who would become her third and final husband. The sheer improbability of Alma’s long-term partnership with the writer Franz Werfel takes one’s breath away. The staunchly monarchist, right-wing matriarch, whose inbred Viennese prejudice against Jews was hardening into a virulent anti-Semitism, and the younger, anti-establishment, physically nondescript Jewish writer, would seem the most unlikely of couples. But, for Alma, Werfel combined the two essentials: sexual affinity – although it took her a while to come to terms with his fetish for the physically mutilated – and talent. What made him especially enticing was the fact that his talent was latent, and it was she who would nurture it. Werfel realised this too. He admitted late in life: ‘If I hadn’t met Alma I would have written a few good poems and gone to the dogs.’ Although they quarrelled incessantly and Alma continually put Werfel down in public, it was Alma’s strength and determination that got them through their hair-raising escape from Nazi-occupied France, and she was a constant support to him in his final illness.

Their life in America was made considerably more comfortable by the phenomenal success of Werfel’s novel The Song of Bernadette (1941). Alma gathered around them other Austrian and German exiles in both Los Angeles and New York and made new conquests, among them Erich Maria Remarque, who was won over not so much by Alma’s charm as by the fact that she could match him glass for glass.

After Werfel’s death in 1945, Alma retreated to New York where she spent her time working on her memoirs. With constant reference to Alma’s memoirs and diaries, Haste tells this story almost entirely from Alma’s point of view. The problem is, as Norman Lebrecht has pointed out, ‘nothing she writes can be accepted without corroboration’, except for her unexpurgated diaries. Haste however quotes liberally from her published and unpublished memoirs, which Alma carefully polished to put herself in the best possible light. But Haste also pulls no punches when it comes to Alma’s anti-Semitism, quoting her approving remarks about Hitler and her almost unhinged rants about Jewish domination. This, after all, was a woman who was capable of calling her children with Jewish fathers ‘half-breeds’.

Haste’s very readable book gives us a positive slant on a fascinating, contradictory figure. Albrecht, who became Werfel’s assistant and later married Alma’s daughter, Anna, was no fan of Alma’s, but he spoke for many when he said that her gift was a ‘profound, uncanny understanding of what it was that (creative) men tried to achieve, an enthusiastic, orgiastic persuasion that they could do what they aimed at, and that she, Alma, fully understood what it was’.

Comments powered by CComment