- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Just over one hundred years ago, Sydney readers were speaking in hushed tones about a shocking new book by a young woman, Zora Cross. A collection of love poems by an unknown would not normally have roused much interest, but because they came from a woman, and were frankly and emphatically erotic, the book was a sensation. It wasn’t, as a Bulletin reviewer said demurely, a set of sonnets to the beloved’s eyebrows. It was ‘well, all of him’. It broke the literary convention that restricted the expression of sexual pleasure to a male lover. Cross took Shakespeare’s sonnets as her inspiration. Her Songs of Love and Life (1917) was a long way from being Shakespearean, but it roused huge admiration. Cross was hailed as a genius, ‘an Australian Sappho’.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Shelf Life of Zora Cross

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $29.95 pb, 285 pp, 9781925835533

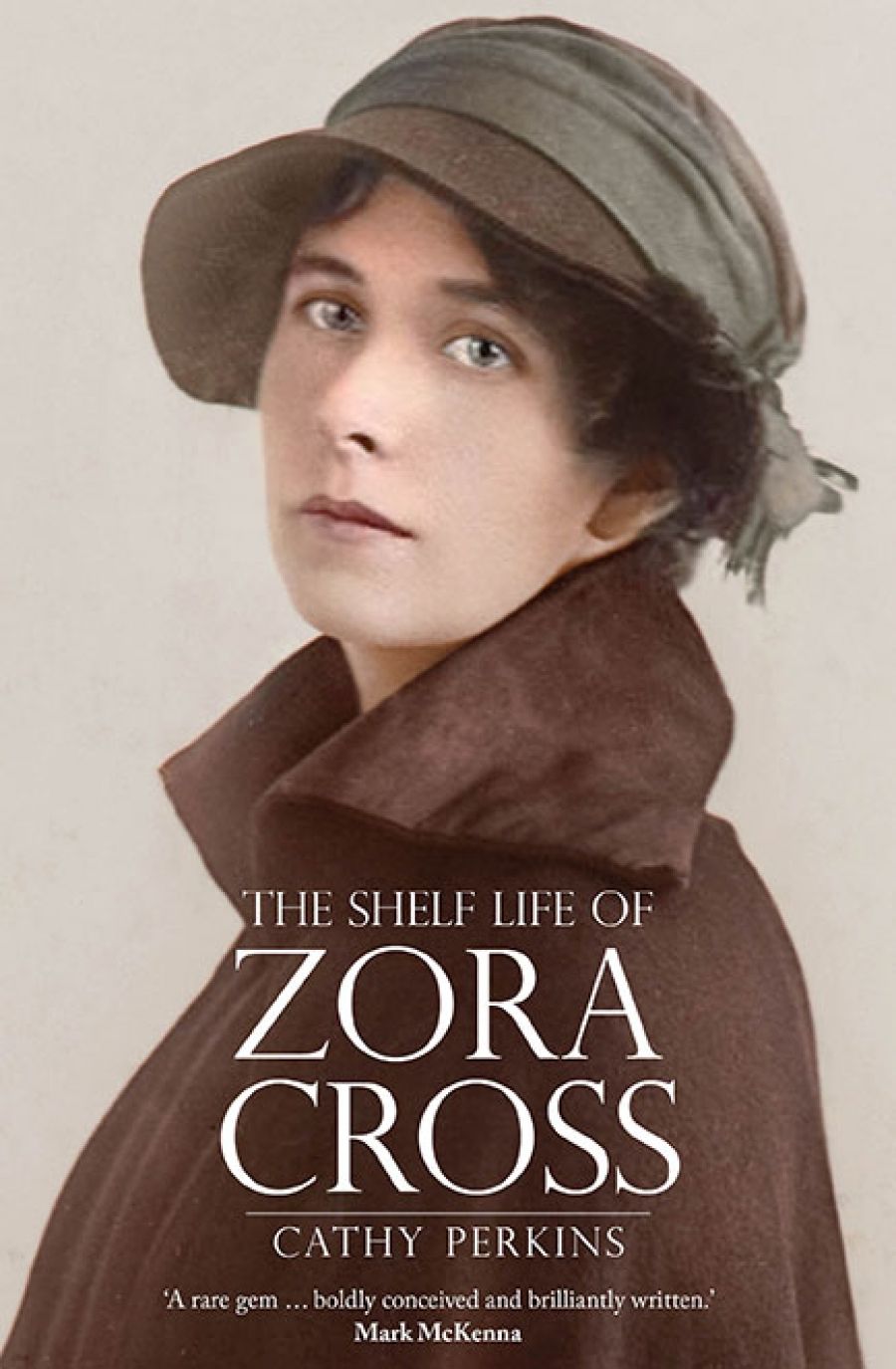

Zora Cross (photograph via the State Library of New South Wales)

Zora Cross (photograph via the State Library of New South Wales)

Although she seldom encouraged her Corner children in career ambitions, Turner liked the fresh and funny letters from Pie Creek Road. When Cross came to live in Sydney, she was invited to Turner’s house in Mosman for advice on how and where to publish. In 1911, Cross confided that she was four months’ pregnant. Turner wasn’t censorious but was concerned that Cross’s life might be ‘like fighting through an endless wood’. She was relieved when Cross married the presumed father of her child. That marriage, however, was over within a few months. The child, a daughter, died soon after birth. In 1914, Zora’s son by an unnamed father was left in the care of her parents for five years.

Cross’s career had reached its peak in 1919 when she formed a permanent relationship with the Bulletin literary editor David McKee Wright. He had a teenage son, from an early marriage in New Zealand, and four young sons in Sydney. He was to have two daughters with Cross. Their life together was as harmonious as it could be, given their financial stress, frequent illnesses, and the discomforts of living in a rat-infested house in Glenbrook, on the lower slopes of the Blue Mountains.

While McKee Wright had encouraged the sensuous direction of Cross’s poetry, he thought ‘the wine god boozing at the breast of Aphrodite’ might be ‘a trifle over the odds’. Cross’s most important friend and patron was the Sydney publisher George Robertson, who gave unreserved support and friendship for many years. He struggled to persuade Norman Lindsay, then famous for his erotic drawings and paintings, to illustrate Songs of Love and Life. Lindsay was appalled by Cross’s outpourings of ‘libidinous frenzy’. Her trouble was probably ‘a torpid husband or no husband at all’. Lindsay singled out a clunky line: ‘when passion gnawed me with his thundering ire’. Eventually, he consented to design the cover of Zora’s book, complaining all the way about her ‘amorous piffle’.

Cross’s biographer, Cathy Perkins, sees the ironic comedy in Lindsay’s shocked reaction to a woman trespassing into his own territory. She does not, however, make large claims for Cross’s literary achievements. She quotes liberally, and the reader may judge whether or not the comparisons, made in Cross’s time, with Elizabeth Barrett Browning as well as Sappho and Shakespeare are at all persuasive. Nettie Palmer’s view that Cross had ‘genuine poetic abandon but not the corresponding restraint’ seems fair comment.

An actor as well as a writer, Cross brought an element of theatre to her presentation of self. Nevertheless, it took courage and self-belief to live for writing, as Cross did.

Perkins shapes the narrative in a series of more or less self-contained chapters, each of them centred on an important relationship. With the exception of Cross’s young brother, who was killed in World War I, they are all literary figures.

Cross’s friendships with Ethel Turner and Mary Gilmore open and close the story. In between these two well-established writers, Bertram Stevens, George Robertson, David McKee Wright, and John Le Gay Brereton make their contributions. So, in a different way, does ‘Bernice May’, Cross’s journalistic alter ego, whose columns for the popular Women’s Mirror kept the pot boiling. Rebecca Wiley, George Robertson’s assistant, was one of several friends whose patience was worn down by the ever-demanding Cross. Wiley sewed and knitted for Cross and sent parcels of books on demand from Sydney to Glenbrook, before rebelling, as did Robertson whose warm and friendly letters turned into chilly replies to ‘Dear Madam’.

When Cross died in 1964 at the age of seventy-three, she left an unfinished trilogy set in ancient Rome. A reader’s report had described this ambitious work as ‘melodramatic and undisciplined’. Nothing had changed.

The Shelf Life of Zora Cross is a beguiling narrative of a literary career that never quite matured. Cross’s chaotic life story is splendidly told by Perkins, who has explored many boxes of manuscripts, letters, and newspaper cuttings in the State Library of New South Wales. Zora Cross is allowed to speak for herself and is given an even-handed measure of admiration and understanding. This enigmatically titled biography conveys the pleasures of Cathy Perkins’s search for the many-faceted author.

Comments powered by CComment