- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poem

- Review Article: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I am from a very large island, a continent in fact. Yet smaller islands have meant more to me – trips to Bribie Island with my grandmother to drink shandies and eat crab sandwiches; two years living in an expatriate Australian community on the Malaysian island of Penang; an object lesson in the power of oceans while visiting American Samoa, when my then boyfriend and I were carried by the tide beyond the coral reef we were exploring with snorkels. In my part of the world, small islands often connote tourism, but they also serve other objects. There is a vanishing point where paradise becomes isolation, where utility meets strategy and where purpose matters more than people.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

This war in ‘the islands’ remained a topic of conversation in my family into the 1970s and 1980s. My grandmother’s childhood friends fought in New Guinea, as did her brother. By the end of the war, one in twenty Australians had spent time in Papua or New Guinea. The roots of this connection went further back, and not just for the planter class. Recently, perusing the notes I had taken twenty years earlier, talking with my grandmother about her Townsville childhood, a reference to my great-grandmother working before her marriage as a domestic in ‘the islands’ to Australia’s north caught my eye in a way it had not before.

After the war was over, these ocean and island territories remained in Australia’s orbit, under a Trusteeship system established by the new United Nations. Their blend of isolation and intimacy, external territory which might allow a liberal democracy to invoke dread, became manifest in new ways. The Australian Military Court convened three war-crimes trials on the Australian mainland, at Darwin, but almost three hundred others were run offshore. A few were held in the British colonies of Singapore and Hong Kong, but most were convened at New Guinea’s capital of Rabaul, and on a host of other islands, including Manus Island. Surrendered Japanese were held at detention centres on Manus Island, and in Rabaul, and sometimes those found guilty of war crimes were hanged in these places.

Family memories of the war seeded my knowledge of older island possessions; a nerdy childhood hobby made me aware of others. What self-respecting philatelist in the 1970s could forget the bright shells, birds, fish, and ships of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Christmas Island stamps? I could not have known then, as we made family trips from our Royal Australian Air Force home on Penang to Singapore, that a mere two decades earlier Cocos (Keeling) and Christmas Islands had fallen within its territorial boundaries.

Not satisfied with its brooch in the Pacific, after the war Australia began to collect external territories like pearls strung on a necklace. In the mid-1950s, Australia acquired from Singapore control of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, then Christmas Island. As Britain began to dismantle its empire, it gifted to Australia new territories in the Indian Ocean to complement its Pacific holdings.

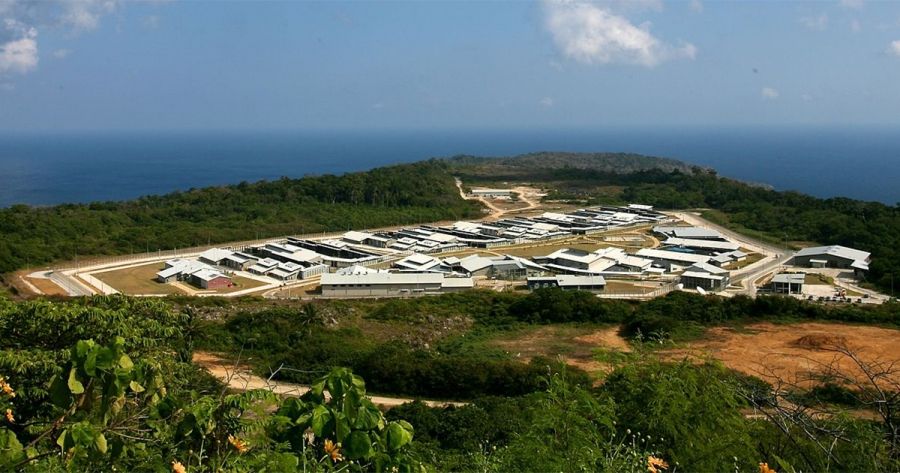

Yet Manus and Christmas Island have become bywords not for security but for desolation. On a recent family holiday, when we arrived at miserable accommodation in the Northern Territory that had promoted itself as ‘safari tents’, the first comment my teenage daughter made was, ‘My God, it looks like Manus Island.’ While the specific situation was a first-world problem, the reach for Manus Island as metaphor for misery and for rows of tent to visually cue an Australian-run detention centre is telling. My daughter has grown up seeing footage of ‘regional processing centres’ on the nightly news, hearing accounts of suicide, death, and suffering within them, and stories about asylum seekers sewing their lips together to protest their detention at centres on Manus Island, Nauru, and Christmas Island.

Recently, the same daughter took part in the climate strike. The day before the strike, when I checked our mail box on the way in through the front gate, my copy of the New York Review of Books had arrived. A photograph of Behrouz Boochani was on the cover. J.M. Coetzee had written the lead essay, entitled ‘Australia’s Detention Islands’. There are periodic, and smaller, demonstrations in Australia about the fate of asylum seekers in immigration detention, but their fate has yet to inspire hundreds of thousands of people to march through our city streets.

Extraterritoriality in the form of islands has bequeathed the Australian state the capacity to practise terror in the name of its citizens. The language hardens in each successive iteration of the strategy. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the ‘Pacific Solution’ allowed the government to excise islands from Australia’s migration zone yet house intending migrants on them. It was Pacific in spatial terms, but not peaceful in nature. The Kafkaesque nomenclature of ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ from 2013 was bettered only by the Back to the Future creation of a ‘Department of Home Affairs’ in 2017.

Forms of territoriality, such as Australia exercises over places like Christmas Island, remain an anomaly in an international system committed to decolonisation. It is not among the ‘non self-governing territories’ on the United Nations’ watchlist, and nor are other island territories held by the United States, France, and Britain, which are merely deemed to have undergone a ‘change of status’. In 2010 the United Nations commenced its third International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism, but it seems to have no plan to address the profound issues raised by extraterritoriality. Australia’s use of such zones to violate the rights of people under international conventions for refugees would suggest that terror is the operative word in extraterritoriality.

Comments powered by CComment