- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Andrew Johnson’s first day in the White House was less than promising. Whether, as his supporters claimed, he was suffering from illness and had attempted to self-medicate or had simply been celebrating his new position as vice president, Johnson was devastatingly drunk. It was 3 March 1865, the Civil War was rapidly drawing to a close, and the recently re-elected President Lincoln was to deliver his second inaugural address. In prose that would eventually be inscribed across the walls of his marble memorial, Lincoln reflected on God, war, and the emerging challenge of how to rehabilitate a divided Union. The vice president’s words that day were barely decipherable and after prostrating himself before a Bible and subjecting it to a long wet kiss, he was quickly ushered away.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

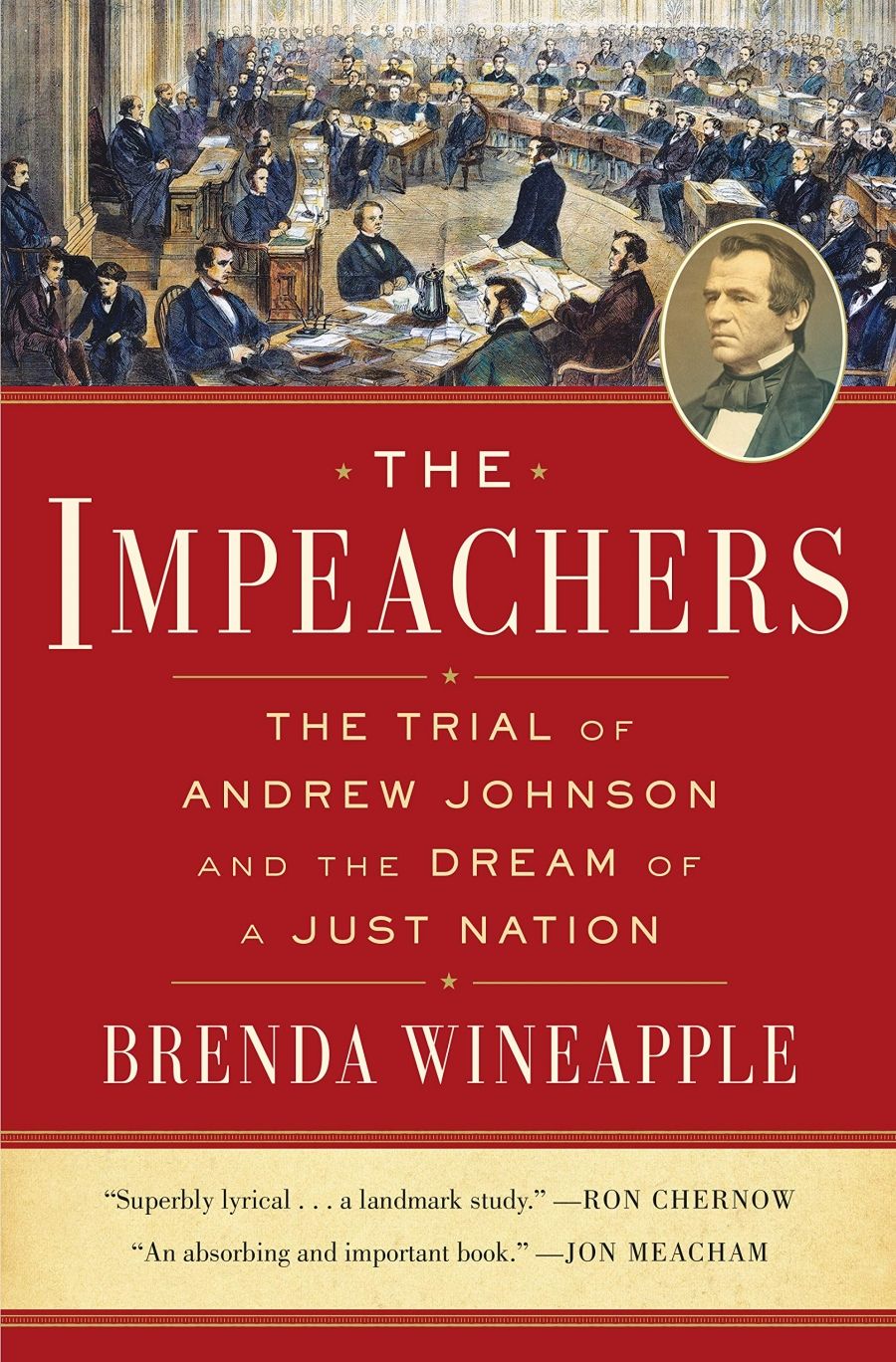

- Book 1 Title: The Impeachers

- Book 1 Subtitle: The trial of Andrew Johnson and the dream of a just nation

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $52.99 hb, 572 pp, 9780812998368

Andrew Johnson (photograph by Mathew Brady/Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

Andrew Johnson (photograph by Mathew Brady/Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

As Brenda Wineapple’s meticulous study highlights, Republicans did not have to wait long for such thinking to be exposed as wishful. It soon became obvious that Johnson planned to welcome the Southern states back into the Union without requiring them to recognise and respect the rights and liberties of the four million formerly enslaved people, despite these rights being central to the moral justification for the war itself (post-1863, at least). As Wineapple demonstrates, it was not one action that brought about Johnson’s impeachment but rather a litany of executive usurpations of power, a refusal to cooperate with Congress or to respect the norms of the office, and a singular devotion to the idea of white supremacy that caused the president to be impeached by the House and acquitted by one vote in the Senate. The president, as Wineapple argues, much more than Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens, or Benjamin Butler combined, bore the greatest responsibility for his own impeachment and the subsequent Senate trial. Although Johnson would survive the trial and serve out the remainder of his term (1865–69), he would leave the White House without any friends or allies in either major party and with a reputation for vindictiveness, arrogance, obstinacy, and bigotry.

The Impeachers is a landmark historical study – arriving as the House of Representatives prepares to impeach the current president and as political pundits furiously debate the merit and function of impeachment. Wineapple began researching and writing this book well before Russia, Ukraine, or Donald Trump’s candidature for the presidency, and it shows. Rather than a clunky, quickly assembled historical analogue to contemporary events, Wineapple presents an impressively crafted analysis of impeachment, Reconstruction, and the drama of high politics. Scouring letters, diaries, and records in archives across the country, Wineapple’s research enriches her portraits of impeachment’s chief protagonists, in much the same way as Doris Kearns Goodwin did in her Team of Rivals: The political genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005). Similar to Goodwin’s collective biography of Lincoln and his cabinet, The Impeachers is no slim volume, yet, like Team of Rivals, it is historical writing at its finest, building tension with each passing chapter and drawing the reader deeper into the emotional lives of these men.

Beyond her skill as a writer, this tension comes about because of what Wineapple argues was at stake in impeachment. It was, of course, about much more than a president defying Congress and simply breaking the law; it was not even really about testing Madisonian democracy and the proper separation of powers. Rather, impeachment signified an intervention by Congress to affirm and determine the course of a new multi-racial democracy, one that affirmed the sentiment of the Declaration of Independence but denounced its hypocrisy.

It is here that Wineapple avoids the pitfalls that other popular writers (particularly in the United States) fall into when describing similarly momentous historical events. Rather than presenting a portrait of great men debating great and lofty principles, Wineapple presents a series of flawed but fascinating characters who were attempting to grapple with a totally unprecedented situation for which the country’s founders had left little instruction. Rather than appealing simply to notions of freedom, equality, and American exceptionalism, Wineapple highlights the devastating consequences of Johnson’s Reconstruction policy for African Americans and Republicans in the South. These included the reinstatement of former Confederates to government offices only months after the end of the war, many of whom took revenge for defeat out on formerly enslaved men, women, and children. Murder, rape, and intimidation were key instruments of white supremacy, and Wineapple doesn’t shy away from highlighting this fact or its connection to Johnson’s policies and rhetoric. For historians of this era, this is nothing new, but for many readers this will be the first time they learn of the violence of this era, of the Memphis and New Orleans Massacres, and that is itself significant.

Although Trump is not mentioned, comparisons between the two presidents are not hard to find. Johnson was a populist who distrusted intellectuals, believed the country should return to some past mythical utopia, and called his political foes enemies of the people, who themselves called the president a demagogue. He loved to campaign and deliver speeches on the stump, yet his inability to stick to the script frustrated aides and was a constant source of political strife and outrage. He even exhorted crowds to hang his congressional opponents in 1866.

As the title suggests, however, The Impeachers is not about Johnson or Trump but rather a group of individuals earnestly attempting to provide a peaceful resolution to a political conflict that threatened to spark another Civil War. For these lawmakers, impeachment meant interrogating the moral purpose of the war and the direction of the country. As Wineapple puts it, impeachment ‘spoke beautifully and with farsighted imagination of the road not yet taken, but that could exist: the path toward a free country, a just country, a country and a people willing to learn from the past, not erase it or repeat it, and create the fair future of which men and women still dream’.

Comments powered by CComment