- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: New Zealand

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australians and New Zealanders know it as the Tasman Sea or more familiarly The Ditch: for Māori, Te Tai o-Rēhua. Significant islands in this stretch of water are Lord Howe and Norfolk. As seen from New Zealand, the island most Australians probably don’t know offhand and, when they are told about it, might feel inclined to reject its name as, well, cheeky: it’s West Island – Australia in short.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

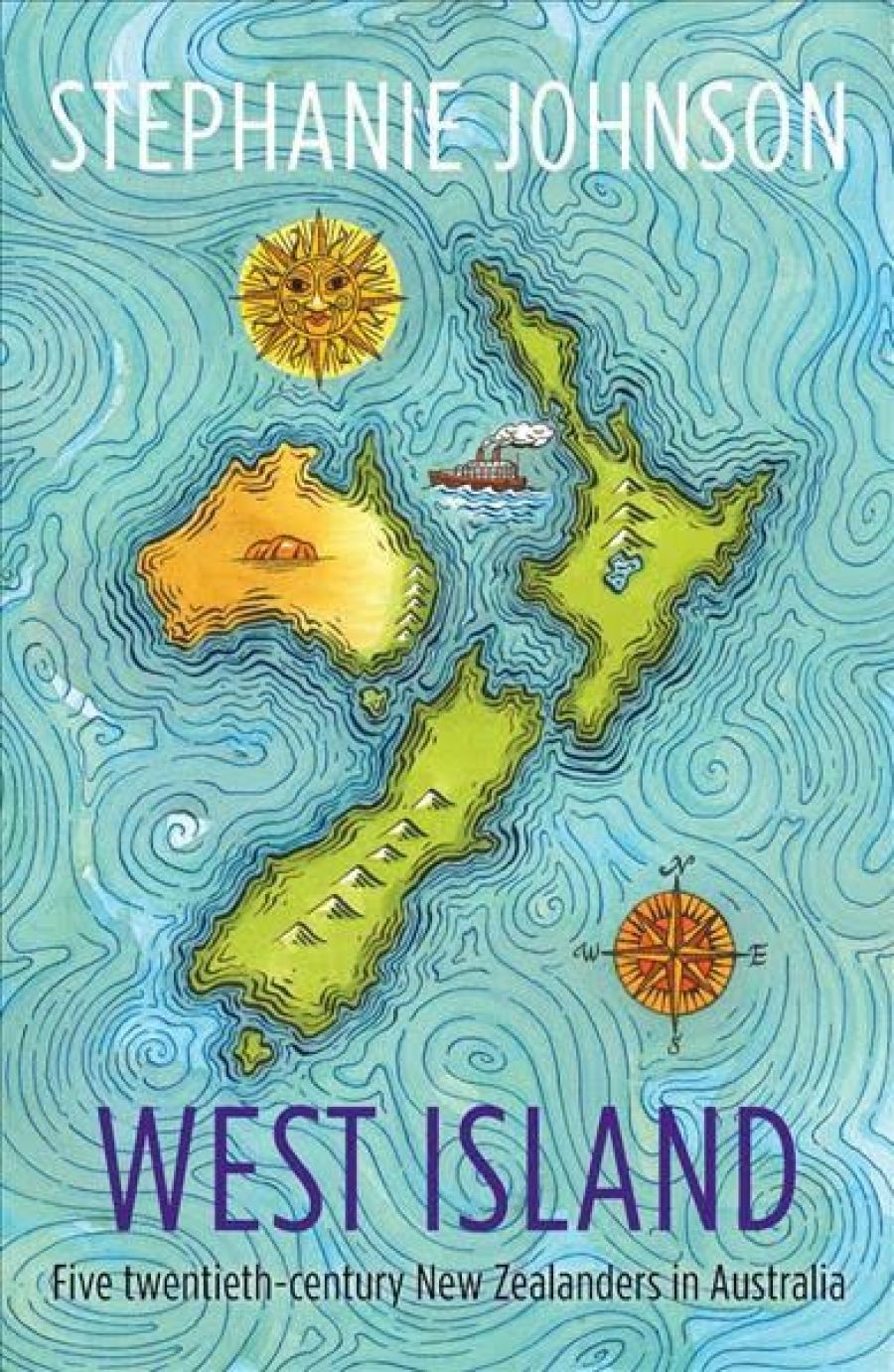

- Book 1 Title: West Island

- Book 1 Subtitle: Five twentieth-century New Zealanders in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Otago University Press, $39.95 pb, 284 pp, 9781988531571

For some readers, this dramatic opening will resonate as a reminder of Johan Huizinga’s similar narrative strategy in The Autumn of the Middle Ages (‘When the world was half a thousand years younger … The cutting cold and the dreaded darkness of winter were more concrete evils’), but, in any case, we follow the warmly dressed strollers to ‘Macquarie Galleries’ where we ‘keep an eye out for the artist, Roland Wakelin’ and come across other New Zealanders in the crowd – ‘all first-generation Pãkehã … Wakelin, Dulcie Deamer, Eric Baume, Jean Devanny and Douglas Stewart’. And so, with no fuss and much panache, Johnson manages the tricky business of marshalling her cast. The curtain is about to go up on West Island but, as it turns out, not quite as expected. ‘When Wakelin, Baume, Devanny and Stewart crossed the Tasman, they were motivated by hopes for better prospects and higher incomes. Dulcie Deamer got on the ship for love and was married when it docked at Perth. My reasons for going were more like hers than the others’, but didn’t result in marriage – and just as well.’

Johnson’s entry into the narrative with her own West Island story is surprising and seems initially self-indulgent. It is, however, a nicely timed change of pace and focus, providing the colour, heightened intensity, sense of personal cultural upheaval, and sheer risk at the heart of the apparently easy ‘leap’ across the Ditch – a reminder that Johnson as novelist and playwright has won New Zealand’s most important literary awards in both genres.

As she follows each of her five peripatetic New Zealanders, Johnson examines and reveals their personalities, aspirations, how and why some were forced or tempted from their planned West Island path, and, in that process, she sketches vividly the nature of the times that they, and the native West Islanders, had to endure or in good years enjoyed. So, Wakelin, after modest success, leaves Australia for London in 1922, and goes to Paris the following year. Of a Van Gogh exhibition he wrote, ‘It burst upon me like an explosion … It was a revelation; none of the few prints we had seen in Sydney could reproduce the vitality of the paint itself.’

Dulcie Deamer in leopard-skin costume, 1924 (photograph via State Library of New South Wales collection/Wikimedia Commons)

Dulcie Deamer in leopard-skin costume, 1924 (photograph via State Library of New South Wales collection/Wikimedia Commons)

Dulcie Deamer, arriving as a young bride, ‘loves her new life’, is overwhelmed by Sydney, ‘staggered … by this metropolis. Hansom cabs everywhere – and motor cars’, and, for the time being, at least, is undeterred by realities like a ‘one-quid-a-week room in Barcom Street, Kings Cross’. Douglas Stewart, as editor of The Bulletin’s ‘Red Page’, remembers this time as ‘tremendously exciting … We did feel that we were at the centre of the movement of Australian culture at that time.’ Eric Baume lives, as ever, flamboyantly and irresponsibly, and Jean Devanny continues to write, falls out of love with the Communist Party and in love with Queensland. As in Britain’s Once an Australian, each character requires a precise biography that Johnson provides with what we come to recognise as expert ease. These include details of the plots of various novels – a necessary but occasionally ponderous recourse, which introduces some longueurs into a complex narrative – and some smoothly infiltrated speculation: ‘Perhaps on …’; ‘Perhaps who …’; ‘It could be …’; ‘Let’s imagine …’

There are deliberate departures from the West Islanders and their adventures: the section called ‘Baume’s Novel Half-Caste’, for example, begins, ‘First, a digression’ and goes on to discuss some ‘lost’ New Zealand classics. Johnson chooses Maori Girl by Noel Hilliard (1960), in which Netta, the Māori girl, is abandoned by her Pãkehã lover; and The Witch’s Thorn by Ruth Park (1951), which ‘suffers from the incipient and highly damaging racism of the time’. Johnson’s last pages – ‘A Comedy Really’ – also seem digressive until the tow-truck driver recalls his visit to Melbourne. ‘He didn’t like the number of Asians coming in [and] … on a tram … couldn’t spot any Aussies at all that he recognised.’

In the afterword, West Island’s quiet but gnawing subtext, one of incipient racism in New Zealand and constant, often official, racism in Australia, is confronting: ‘Despite decades – centuries – of immigration from all over the world, Australia is racist.’ As for the relationship, ‘the situation, in light of our shared history, is barbaric’.

West Island is engaging, deceptively playful, written with great style and brio, and, on reflection, provides a disturbing and apposite portrait of the way we Islanders are in the first decades of the twenty-first century.

Comments powered by CComment