- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seeing Truganini

- Online Only: No

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922)

For what it is worth, my own view is that in contemporary Australia the dialectical quest for truth about the indigenous culture, by open argument and counter-argument, is no less important than about the culture of the invaders and oppressors. Both investigations, I believe, are best carried on by scholars whose primary loyalty is not to one heritage or the other but to the principle that nothing is sacrosanct except the spirit of free inquiry itself. The custodians of that particular flame are without race, as are their enemies.

L.R. Hiatt, Arguments about Aborigines: Australia and the Evolution of Social Anthropology (1996)

One morning early in 1994, a week or so after I began work at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, a colleague breezed into my office and dropped an envelope on my desk.

‘Thought you should see this,’ he said. ‘Thought you should know about the institution you’ve come to work for.’

I opened the flap and withdrew an eight-by-ten photographic print. It was a pretty confronting shot. It showed an exhibit: a small timber and glass case of no more than four or five cubic metres capacity, into which was compressed the whole of the culture and nineteenth-century history of the Palawa, the Tasmanian Aboriginal people. Framed and hanging at the top rear of the vitrine were 1830s portrait watercolours by the convict artist Thomas Bock and 1860s ‘anthropological’ photographs by Charles Woolley, a bas-relief plaster death mask and one of Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur’s famous ‘proclamation boards’. Below, on a plinth, was a bust of the Nuenonne tribal leader Woureddy. On the ground there was a scatter of grinding stones and abalone shells. Spears and waddies leaned up against the back wall, from which hung swags of shell necklaces, woven grass baskets, models of bark canoes. And right in the middle, mounted on a steel frame, standing on a black box which highlighted its smallness and fragility, was a human skeleton. A label proclaimed it to be that of ‘Lalla Rookh or Truganini. The Last Tasmanian Aborigine.’

I knew about Truganini’s skeleton, of course. I had done my history homework when I accepted the job. A replica had been displayed in the Museum of Victoria when I was a child. It was, as I recall, just to the left of the door that led into a room containing a number of Egyptian sarcophagi, one of them with parts of the skeleton visible through the mummy wrappings. And then, adjacent to the Egyptiana, there was an ethnographic gallery that included both a preserved Maori skull, with full facial tattoos, and a couple of Amazonian shrunken heads. These are the sorts of grisly encounters that little boys delight in (and remember forty years later): glimpses of the mortality mystery that the juvenile mind can only partly comprehend.

In grown-up Tasmania, extinction – of Aborigines and thylacines, at least – was fully known, fully upfront. Truganini’s bodily remains were on public display in the Museum from 1904 until as late as 1947. They were not returned to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community until 1976, a hundred years after Truganini’s death. That year, her skeleton was ceremonially cremated, and on 1 May the ashes were scattered in the waters of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel, near her birthplace, Lunawannaloona (Bruny Island).

Nineteen forty-seven? I idly ran the arithmetic through my head and deduced that many ‘born and bred’ Tasmanians in their late fifties or older would probably have seen Truganini on display in her glass case, would have formed their ideas of Aboriginal culture and society and history from that encounter, would have had the myth of ‘The Last Tasmanian Aborigine’ reinforced by the apparently incontrovertible evidence of the bones. Well, the Hobartians would, at least. In Launceston and the North West, the Bass Strait Islander families – the Maynards and the Mansells, the Browns and the Everetts – provided inconvenient, embarrassing living proof of black survival.

Such were the thoughts that this singular photograph began to provoke, connections that arose both in the memory and in the more conscious, academic mind. This was clearly a power object, even in its diluted, unoriginal ‘print from a copy neg’ form. The authenticity of the image, the physical and historical and human truth recorded by the anonymous photographer, was palpable.

The picture continued to haunt me over the next ten years as I pursued my curator’s investigations of the Museum’s collections, and my personal reading of Tasmanian history in particular and of Aboriginal–settler contact history in general. In this same period, the Australian nation worked through the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, the implicit racism of the One Nation Party, the High Court’s Wik decision on Native Title and the Howard government’s Ten Point Plan in response, the prime minister’s refusal to apologise to the Stolen Generations, and the review and eventual abolition of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. It was a difficult decade in many ways.

The so-called History Wars, the ideological conflict between ‘Black Armband’ and ‘Whitewash’ got into full swing. Henry Reynolds published half a dozen thoughtful, expansive titles on frontier conflict, from Fate of a Free People (1995) to This Whispering in our Hearts (1998); Keith Windschuttle responded with the mean mortuary accounting of The Fabrication of Aboriginal History. Volume 1, Van Diemen’s Land 1803–1847 (2002). Meanwhile, the Tasmanian Museum itself, feeling increasingly conscious of, and accountable for, both its historical shame and its contemporary responsibilities, moved to build and strengthen relationships with the local Aboriginal community, to reorient itself from conquest museum to reconciliation keeping place. Anthropology was renamed, and a Palawa man, Tony Brown, was appointed to a trainee curatorship in the new department of Indigenous Cultures.

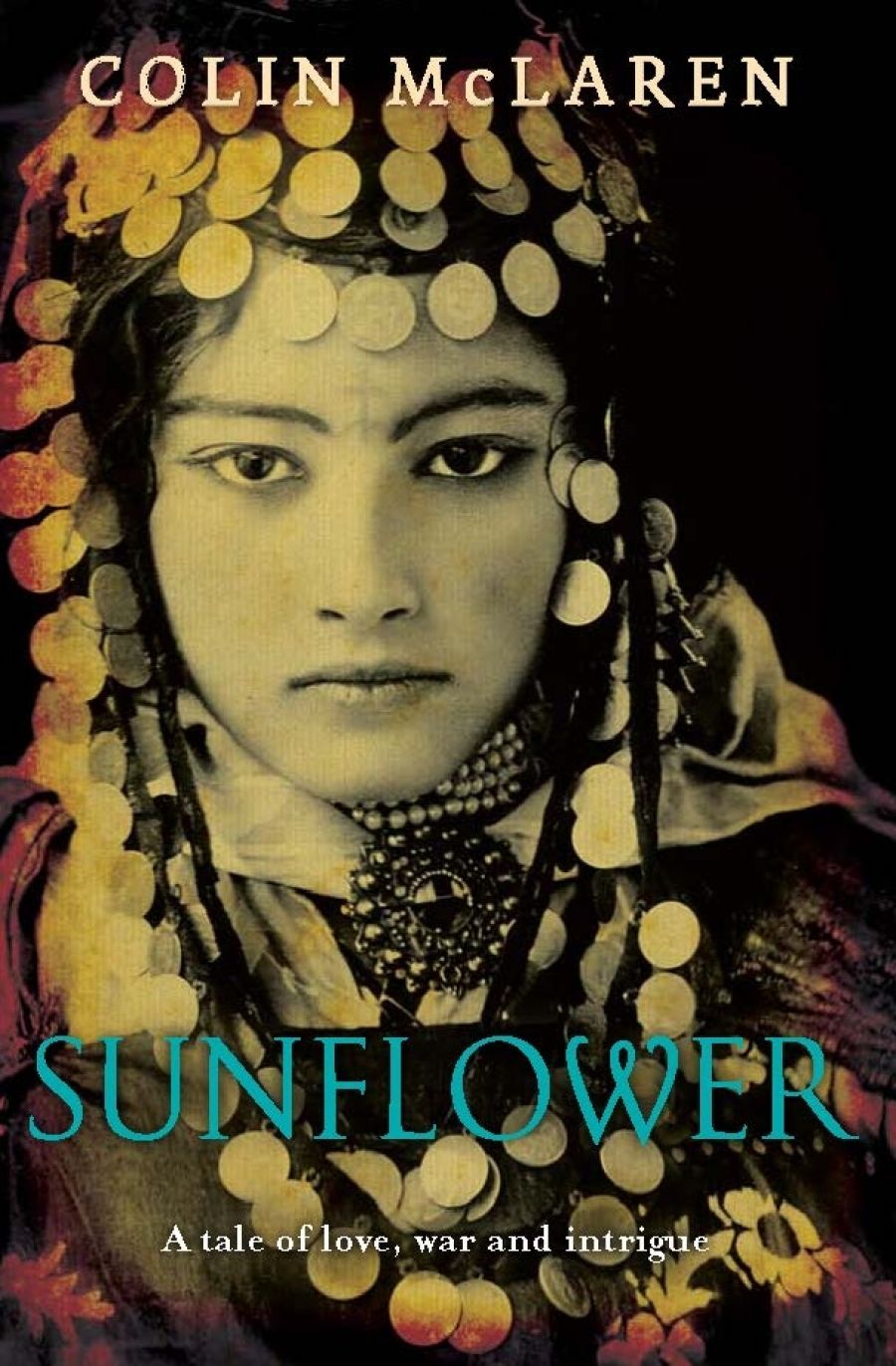

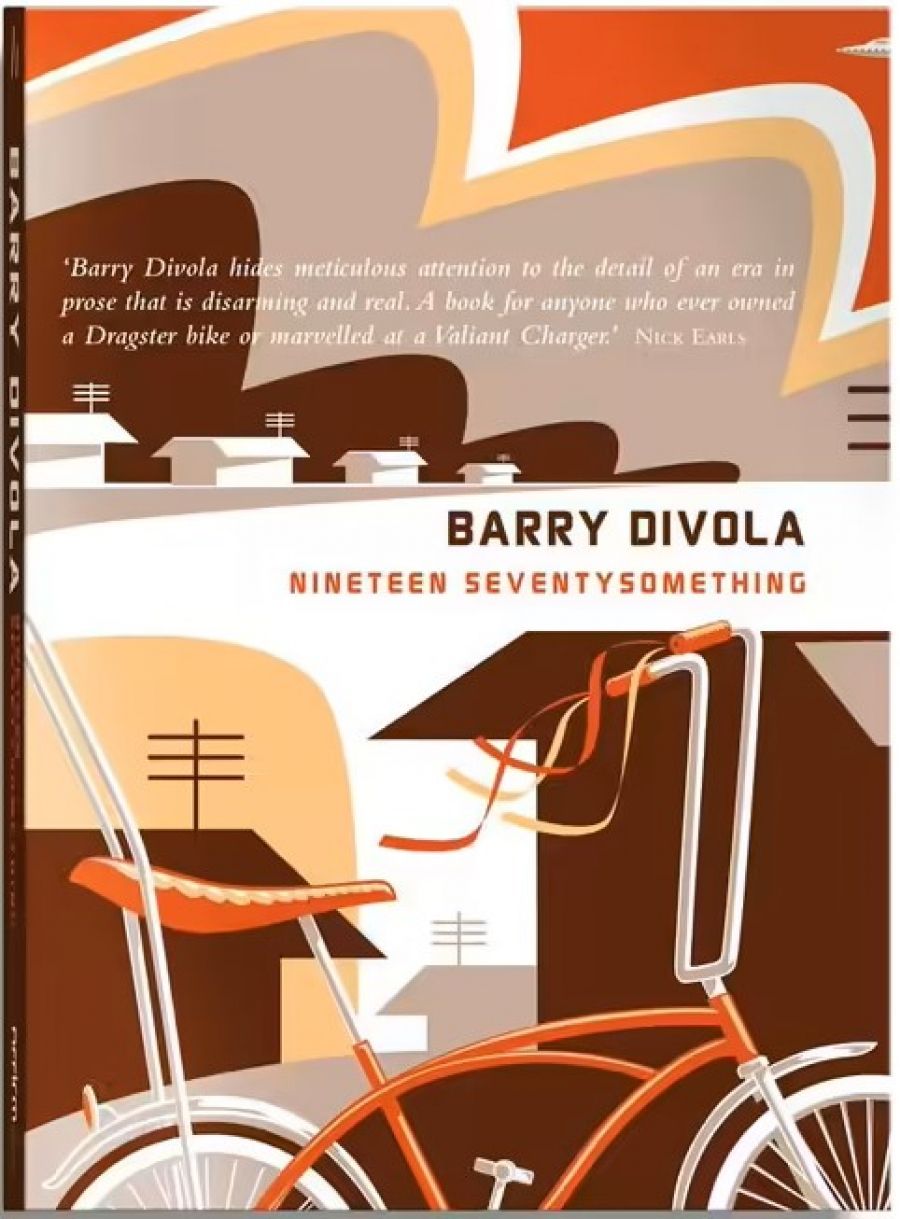

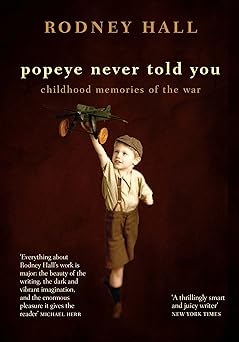

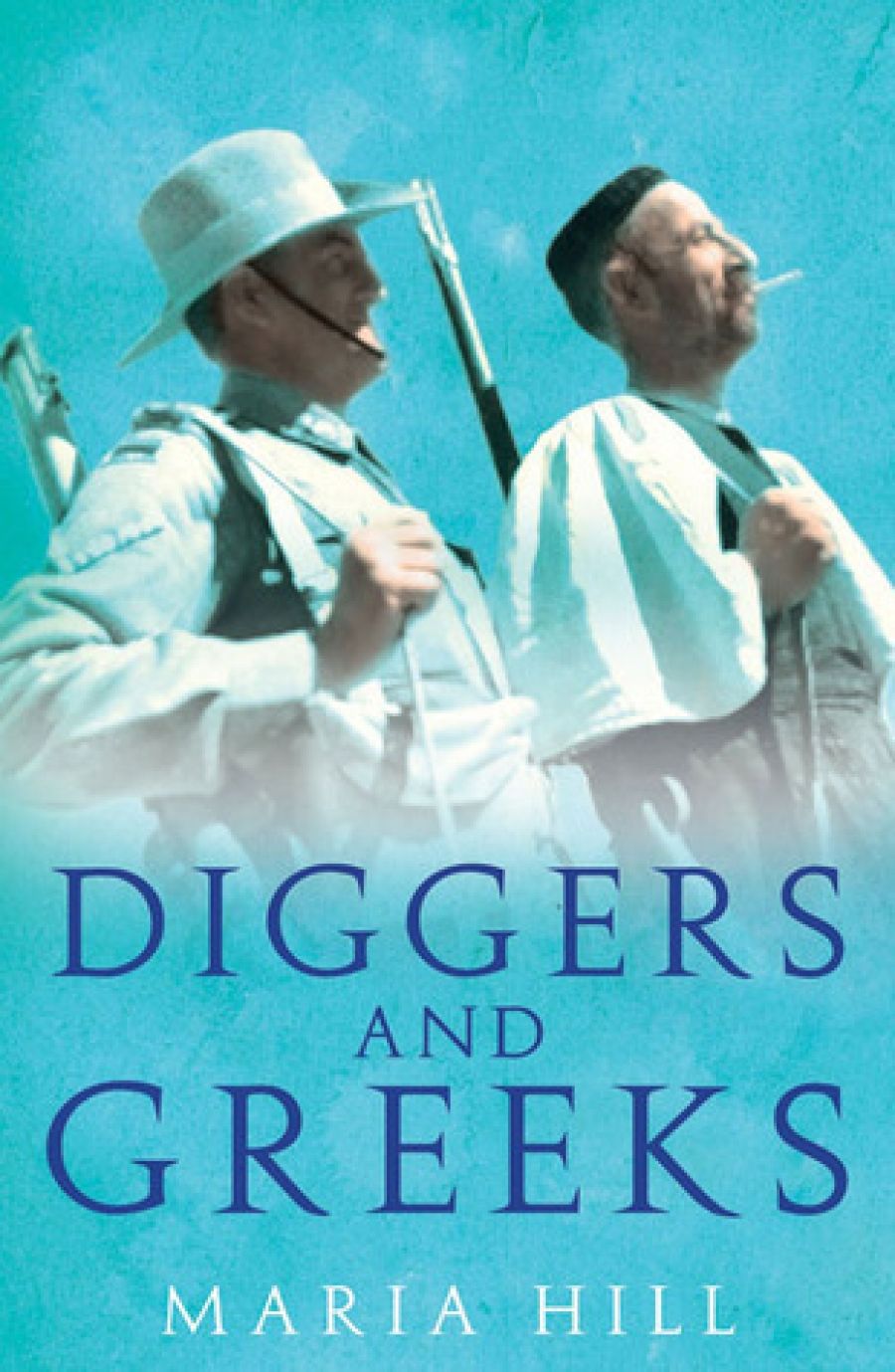

Robert Dowling, Tasmanian Aborigines 1856–57, (courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria)

Robert Dowling, Tasmanian Aborigines 1856–57, (courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria)

Amidst all these rhetorical gestures, all this ideological push and shove, there were times when I dearly wished I could have shown what I had come to think of simply as The Picture, either on its own, or within collection displays, or as part of an exhibition on the broader themes of conflict and reconciliation. I wanted to know other people’s reactions to it; wanted to share a variety of recollections, interpretations and storytelling by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal commentators. But while I was possessed by the visceral power of the image, its extraordinary visual and historical richness, the possibilities it offered for subtle, creative exegesis, I recognised that I would never be able to display it publicly. In that particular historical, geographical, social and organisational context, The Picture was clearly taboo.

For Aboriginal Tasmanians it was a clear insult, both to a deceased ancestor and important community leader, as well as to the Palawa at large. For the Tasmanian Museum, it was evidence of the institution’s complicity in ‘scientific’ grave-robbing, in the worldwide nineteenth-century trade in indigenous skeletal material, and in perpetuating the myth of the Tasmanian genocide. It was also an uncomfortable reminder of the problem of sundry unidentified and unprovenanced human remains still pulsing radioactively in the Museum’s restricted-access storeroom. For both parties, this photograph would bring the past rather too uncomfortably into the present.

I considered alternative curatorial strategies. Perhaps we could display the picture in a separate area, behind a screen or curtain, with a warning about disturbing content. Or we could recreate the display and build a facsimile of the original vitrine, complete in all its details save for the skeleton itself. After all, the Museum still owned all the other stuff, all the art and artefacts. More cheaply, we could simply digitally edit the photograph and white-out the skeleton.

In the end, of course, I did nothing, for all the usual whitefella reasons. It was easier. There were plenty of other things on my plate at the time, and it wasn’t really my responsibility. While I was nominally Co-ordinating Curator of Art and Humanities, with a watching brief over History, Decorative Arts, Photography and Indigenous Cultures (all the disciplines represented in the vitrine), that was really a stopgap administrative convenience; I was mainly just the Art Guy. Besides, indigenous matters were particularly sensitive and always, and properly, necessitated both slow, complex community negotiations and the highest-level managerial and political sanction. Not my field. Beyond my competence. And they’d say no, anyway.

In the end, I felt I could probably do more by concentrating on the effective display and interpretation of material in my immediate care: Bock’s delicate watercolours of George Augustus Robinson’s ‘sable companions’ and of Mathinna, the pretty, barefoot girl in the red dress adopted for a time by Sir John and Lady Franklin; the fleeting images of Aborigines in the sketchbooks and landscapes of the observant, curious John Glover; Benjamin Duterrau’s ambitious history painting The Conciliation (1840) and its various associated prints and plaster reliefs; and an anonymous artist’s remarkable image of an Aboriginal guerrilla attack on the East Coast farm of settler John Allen during the Black War of 1828.

Thus did I talk myself out of that difficult artefactual corner. Thus did I avoid becoming mired in the slough of post-colonial despond. And I let The Picture, with its compelling visual, historical and political actualities, continue to lie hidden, unexamined, unexplained.

There was something else that took the wind out of my sails, out of the cape of the would-be curatorial crusader: the discovery that the image was in fact already in the public domain. It was published in 1977 in Dan Sprod’s Victorian and Edwardian Hobart from Old Photographs,1 a book freely available in the State Library of Tasmania, the University of Tasmania Library – the Museum Library even. You could usually find a copy in one of Hobart’s antiquarian bookshops. By the time I left the Museum in 2004, you could even see The Picture on three or four websites.

In some ways, this made the situation even more difficult to deal with: professionally, ethically, morally. Here were public servants, public scholars in a state-funded museum who could not or would not display, let alone discuss, an important historical and cultural artefact, ostensibly out of respect for indigenous culture. I and my colleagues at the Museum were not only the authorised, official, institutional custodians of this image, but also had between us both the ethno-graphic and historical knowledge and the access to associated documentary and collection resources to be able to present, contextualise and interpret this most complex, layered image; yet in deference to indigenous sensitivities we remained silent.

My Tasmanian silence echoes in much historical and particularly art-historical writing. For settler Australian scholars with a conscience or simply a political consciousness, it seems absolutely necessary to correct British triumphalism and exclusivism and to fill the indigenous and immigrant gaps in the national record of visual culture. The year I arrived in Hobart, Andrew Sayers published his fine survey Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century (1994), introducing many Australians for the first time to such major figures as (William) Barak, Yackaduna (Tommy McRae) and Mickey of Ulladulla. Sayers’s book begins with a quite remarkable opposition of two works of art: a pencil drawing of the young Aboriginal ‘Black Johnny’ or ‘Johnny Dawson’ by the Austrian emigré Eugene von Guérard, and Johnny’s own portrait of von Guérard at work sketching. Dating from von Guérard’s visit to the Western District of Victoria in the winter of 1855, the two portraits were probably made on ‘Kangatong’, the estate of James Dawson, the man who commissioned one of von Guérard’s first Australian landscapes, Tower Hill (1855), whose interest in the language and culture of the local Aboriginal people, the Kirrae Wurrung, was almost unique amongst the pastoralists of the Port Phillip District, and who, in later life, would erect a handsome monument to Wombeetch Puyuun or ‘Camperdown George’, known as ‘the last of the local tribes’.2

‘For settler Australian scholars with a conscience or simply a political consciousness, it seems absolutely necessary to correct British triumphalism and exclusivism and to fill the indigenous and immigrant gaps in the national record of visual culture’

Such retrievals from the archive are vital. In the case of the Johnny–Eugene portrait pair, they can be charming, even moving in their summoning of harmonious Aboriginal–settler interaction on the frontier, no matter how rare that might have been. However, due to the very nature of traditional Aboriginal cultural practices and to the rapidity of white incursion, very little nineteenth-century Aboriginal art survives intact. Art historians’ consideration of the question of race relations in the contact zone therefore more usually takes the form of academic deconstruction of settler paintings which feature Aboriginal subjects.

Here we find ourselves not in embarrassed silence, but in the equally regrettable white noise of pious post-colonial cant, a world of ‘unequal power relations’, ‘the imperial project’, ‘post-Enlightenment tropes’, ‘binaries’, ‘imaginaries’, ‘agency’ and, of course, ‘discourse’. All too rarely are we given such things as primary sources, site investigations, and assessments of personal motives. With notable exceptions such as Paul Fox and Jennifer Phipps, Tom Griffiths, John Jones, Philip Jones and John McPhee (and these are all experienced curators, materialists), few academics choose to address the gritty specificities of life on the frontier.3 Representations of Aborigines are not calibrated against the lie of the land, the history of the invasion, the character of the parties involved, the specific sequence of particular incidents, or the sensitivity and technical accomplishment of the artist. Instead, we are presented with an abstract zone of retrospective judgement, a killing field of theory, a terra nullius where imported European aesthetic stock – the Picturesque, the Sublime, the Grotesque, the Melancholy – may safely graze.

Thus, the National Gallery of Victoria’s permanent collection display of early nineteenth-century Australian painting was in recent years rehung in postmodern mode, with its array of Aboriginal subjects including not only works by von Guérard, Glover and Robert Dowling, but also by the contemporary Wiradjuri artist Brook Andrew. Such trans-historical adjacency can be a useful museological technique; since the 1980s, ‘interventions’ by contemporary artists have become a staple of gallery programs worldwide. In this instance, the disruption to the straightforward, diachronic presentation was Andrew’s well-known Sexy and Dangerous (1996). A striking image of a handsome young Yirrganydji chief from Barron River, Queensland, appropriated and modified from a Charles Kerry photograph taken around the turn of the twentieth century, Sexy and Dangerous was a useful prompt for viewers to reconsider their prejudices and assumptions with regard to the look of Aboriginality, past and present.

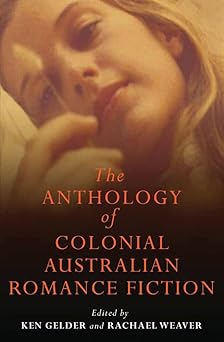

However, beyond the surprising, refreshing disjunction of medium and style, the new arrangement offered viewers little in the way of a point of entry into either the works or the issues with which they were confronted. The Dowling, for instance, Tasmanian Aborigines, is a particularly interesting picture. One of three similar works painted just before the artist left Van Diemen’s Land to study in London, it is partly documentary and partly nostalgic, partly classical and partly exotic. Dowling represents a group of ten Palawa gathered around a campfire in the wilderness, beneath the distant plateau and Organ Pipes of Mount Wellington. When this picture was painted (c.1856–57) there were only some sixteen ‘full-blood’ Tasmanian Aborigines left alive, all of them at the government settlement at Oyster Cove, south of Hobart Town. While the painting’s background might well suggest a view from that location, those few surviving Palawa certainly didn’t look like this group. At just around this time, Bishop Francis Russell Nixon photographed the Oyster Cove Aborigines, who sported long print dresses, waistcoats, woollen scarves and flop-top beanies. Dowling’s ‘noble savages’ are in fact direct transcriptions of the 1830s watercolours of Thomas Bock, from a set copied by the artist for Dowling’s father, the Rev. Henry Dowling. By comparing these originals with Dowling’s composition, we can identify these people by name. They are (standing, from the left): Timme (‘Bob’) from George’s River; Tunnerminnerwate or Peevay (‘Jack of Cape Grim’); Probelatena (‘Jemmy’) from the Hampshire Hills; (seated) an unidentifiable female; Truganini; an unidentifiable back-view figure; Larretong (‘Queen Andromache’) from Robbins Island; Woureddy (‘The Doctor’) from Bruny Island; Numbloote (‘Jenny’) from Port Sorell; and the East Coast chief Manalargenna.4 Yet with all this (and more) information readily accessible, the Gallery chose instead for its wall text an extended passage of dense post-colonial theory by the Palestinian–American intellectualEdward Said, a quote from his film The Shadow of the West (1986).5 No explanatory historical detail. No dignity of naming.

There is a grave risk in the contemporary emphasis on interpretation. Because the traditional, nineteenth-century way of doing art history is, these days, conventionally understood as complicit in the supposedly oppressive semiological and scopic régimes of the so-called Enlightenment Project, we stand back a little. The politically correct commentaries of the New Art History don’t actually touch the work of art, but sit above it, parallel to its surface, like a scrim of fine gauze, or that 1970s first generation of non-reflective glass. Fashionable academic casuistry actually blurs historical reality and, when there is difficulty or conflict, leaves you no clear point of view, no solid place to stand.6

‘Sotheby’s, Sotheby’s, leave them alone! Let us take our ancestors home!’ The chanting from the five women on the footpath outside drifted into the auction room every time the door opened. It was August 2009, and I was now working as a researcher for Sotheby’s Australia. Led by Nala Mansell-McKenna and Sarah Maynard, a delegation from the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre was in Melbourne to protest the sale of a pair of plaster busts of Truganini and Woureddy by the Sheffield silversmith and colonial settler Benjamin Law. Ironically, the Woureddy in the Tasmanian Museum’s Aboriginal vitrine was cast from this same edition.

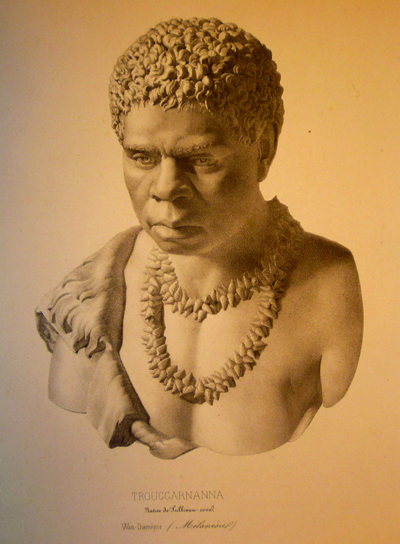

These two extraordinary works of art, the first sculptures made and exhibited in British Australia, combine a high level of artistic literacy and manual skill (in the neoclassical, Roman style of busts and socles), of careful ethnographic observation (in the kangaroo-skin cloaks, in Truganini’s close-cropped hair and maireener shell necklaces, in Woureddy’s ochred dreadlocks and kangaroo-sinew torcs); and what appears to have been an acute eye for likeness and character. Made in Hobart Town in 1835 and 1836, when the local fame of ‘The Conciliator’ George Augustus Robinson and his Palawa negotiating team was at its height, Law’s busts were warmly received, the naturalist and journalist John Lhotsky describing them as ‘perfect likenesses … altogether a respectable work’.7 Several of the edition of some thirty casts were bought by Lieutenant-Governor Arthur, while others were sent abroad: to England and Scotland, even India and Sweden. Later overlooked by Australian art historians, they were reconsidered and admitted to the canon during the 1980s. Since then pairs of busts have been acquired and placed on permanent display in the National Gallery of Australia and most state art galleries.

For the demonstrators, however, the art history of the busts was irrelevant. The chanting and Aboriginal flag-waving of the women outside Sotheby’s were at once symbolic protests and protests against symbols. In the first instance, Woureddy and Truganini, and especially Truganini, still stand as signifiers of the Tasmanian Aborigines’ extirpation. In nineteenth-century anthropological discourse, with its setting of British imperial supremacism and Social Darwinist racism, the death of ‘The Last Tasmanian Aborigine’ illustrated the superiority of Anglo-Saxon civilisation and the inevitable decline and disappearance of indigenous peoples, not only in Australia but across the world. Of course, such cold scientism was never the whole story of European colonial attitudes. For some settlers, such as James Dawson, the dispossession and deaths of Aboriginal populations were deeply troubling.

But regardless of the moral and political stance adopted by contemporary white witnesses and interpreters, the extinction of the race was quickly and widely accepted as fact, and largely remains so in the popular imagination. Truganini is every bit as much ‘The Last Tasmanian Aborigine’ in Robert Drewe’s 1978 novel The Savage Crows, in Bernard Smith’s 1980 Boyer Lectures, The Spectre of Truganini, in Gordon Bennett’s 1989 painting Requiem, and in Midnight Oil’s rock album Truganini (1993), as she is in her glass case in The Picture.8

Indeed, it was the title of a largely sympathetic account, Tom Haydon’s passionate and sorrowful documentary The Last Tasmanian (1978), that prompted some of Aboriginal Tasmania’s earliest public assertions of survival and identity. The film’s poster, with its central image of Truganini staring into Charles Woolley’s camera lens, carried the tagline ‘The story of the swiftest and most effective genocide on record’. Angry at being thus denied their very existence, Aboriginal Tasmanians picketed cinemas, the young Michael Mansell debated with the film’s director on ABC television’s Monday Conference and mainland, mainstream Australia got a swift kick in the socio-historical assumptions.

Since that time, the racial and familial heritage of the Palawa has been widely and publicly explored and explained. Residual traditional practices – mutton-birding, the collecting, burnishing and stringing of maireener and rice shell necklaces, the making of baskets and vessels from grass and kelp – have been documented, preserved, revived and celebrated. From the word-list ruins of a dozen pre-contact indigenous languages, Tasmanian Aboriginal speech is being revived as palawa kani. In a recent and spectacular piece of cultural reclamation, Tony Brown, at the Tasmanian Museum, coordinated the making of a full-size bark canoe based on the nineteenth-century scale models held in the Museum, the work being undertaken by four Tasmanian Aboriginal men: Brendon ‘Buck’ Brown, Shane Hughes, Sheldon Thomas and Tony Burgess. After generations of denial and shame, some 8000 Tasmanians now proudly self-identify as Aboriginal.

Thierry frères, lithographers, after Benjamin Law (1807–1890), sculptor, Trouggarnanna, Native de Sullivan-cove, Wan-Dieménie (Mélanésie) c.1850, lithograph, from Charles Jacquinot (ed.), Voyage au Pôle Sud et dans l’Océanie: sur les corvettes l’Astrolabe et la Zélée, exécutée ... pendant les années 1837– 1838–1839–1840, sous le commandement de M.J. Dumont d’Urville, Paris: Gide, 1841–1855, Atlas: Anthropologie, plate 23, La Trobe Rare Books Collection, State Library of Victoria

Thierry frères, lithographers, after Benjamin Law (1807–1890), sculptor, Trouggarnanna, Native de Sullivan-cove, Wan-Dieménie (Mélanésie) c.1850, lithograph, from Charles Jacquinot (ed.), Voyage au Pôle Sud et dans l’Océanie: sur les corvettes l’Astrolabe et la Zélée, exécutée ... pendant les années 1837– 1838–1839–1840, sous le commandement de M.J. Dumont d’Urville, Paris: Gide, 1841–1855, Atlas: Anthropologie, plate 23, La Trobe Rare Books Collection, State Library of Victoria

Yet this renaissance has not exorcised ‘the spectre of Truganini’. In 2009, a generation after the release of The Last Tasmanian, the issue was still (for Michael Mansell at least) that the sculptures ‘convey the racist image that they were the last Tasmanian Aboriginal people … To make money out of images that convey such a racist impression [to] the rest of Australia and indeed the world, is to vilify the Aboriginal people now and treat us with ridicule and contempt.’9

Furthermore, this central message was also freighted with implications and with references to other settler offences. The protesters’ demand for the ‘return’ of the bust sounded a strong echo of the rightful moral claims of Aboriginal communities on skeletal and other human remains held in museum collections across the world. This matter remains a particularly sensitive one; after all, it was not until 2005 that London’s Royal College of Surgeons returned their ‘scientific’ samples of Truganini’s hair and skin to her people in Tasmania. Works of art are not such remains.

The issue was further confused through the implicit suggestion that the display of the portraits was somehow inappropriate: ‘If you make a sculpture of the dead, the spirit of those people can be captured.’10 Here, the Aboriginal Tasmanians would appear to have borrowed from their Northern Territory cousins a traditional law protocol in relation to death: the burning or burying of the personal effects of the deceased, and the prohibition on speaking their name for the duration of mourning. In traditional Central Desert culture, these prohibitions are designed to prevent slippage or contamination between the worlds of the living and of the dead. Aborigines recognise that only a thin and permeable boundary separates current, everyday economic and social activity from the fundamental, primordial, metaphysical spaces and structures of where we come from and where we go to: the Dreaming, or, to use anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner’s preferred translation, the Abiding. Border crossings need to be carefully managed by appropriate ceremony, whether at times of initiation, marriage, funerary and other rituals, or when different neighbouring groups meet and exchange songs, dances and stories.

In the whitefella way, in the European, secular, Enlightenment tradition, this ceremony is the practice of history. In doing history, we examine and interpret documents and artefacts in order that the people of the past might live again briefly in the present, and in that resuscitation help us to understand ourselves. In white history’s ritual, its law, its tjukurrpa, you cannot take contemporary understandings and judgements back across the temporal border, only contemporary questions. You can’t tell the dead how to behave, or what to say. Which brings us back to Truganini and the Benjamin Law bust. It is not right that this handsome work of art should be held to stand either as some kind of symbol of the Tasmanian ethnocide or, contrariwise, as an emblem of discredited Social Darwinism. It is not the sculpture that conveys the extinction myth, but the way the image is and has been used in another past, a later past.

Law’s work dates from 1836, when there were still the best part of two hundred ‘full-blood’ Palawa living, more than twenty years before the publication of The Origin of Species, and a good forty years before the sitter’s death. As a recent arrival in the colony keen to make a name for himself, Law made his portraits of Truganini and Woureddy because they were then famous. These two were the longest-serving and most prominent of George Augustus Robinson’s treaty group, the negotiators responsible for bringing an end to the bloody Black War. (Law’s only other known bust, of Robinson himself, has been lost.) The members of the ‘Friendly Mission’ were the heroes of the hour, and had earned the gratitude of the entire settler community; Robinson and ‘his’ people were A-list colonial celebrities. The year after Law made his Truganini bust, Jane Franklin, wife of the new lieutenant-governor, was to commission fourteen watercolour portraits of Robinson’s Palawa friends from Thomas Bock, and that same year 113 residents of Hobart Town would successfully petition the Executive Council, urging the public purchase of Benjamin Dutterau’s oils of Truganini, Woureddy, Tanlebouyer and Manalargenna. The four paintings hung for many years in the chamber of the Tasmanian Legislative Council, and were eventually transferred to the Tasmanian Museum.

Smart and vivacious, young and attractive, Truganini was a particular popular favourite. Nicknamed ‘Lalla Rookh’, after the exotic oriental princess in Thomas Moore’s then enormously popular eponymous poem, she was, like the Kuringgai man Bungaree in Sydney a decade earlier, the leading indigenous pin-up. She even had a boat named after her: a cargo schooner built by William Williamson, in 1838. Before all those 1860s and 1870s photographs, before she inherited the tragic title of ‘The Last Tasmanian Aborigine’, she had been sketched or painted not only by Bock and Dutterau, but also by Glover, Thomas Napier and John Skinner Prout. Law’s bust tallies closely with these paper images in terms of Truganini’s general appearance, but has the greater realism of three dimensions. As the Hobart Town Courier observed at the time, the work is ‘completed in exquisite style closely resembling nature’.11

Because it is a handmade object, because it has required slow, careful scrutiny, certainly well beyond the few seconds of a wet-plate photographic exposure, the sculpture necessarily implies a certain level of communication, of relationship between artist and sitter. This assumption would seem to be borne out by an 1838 letter written by Law’s wife, Hannah. The Laws’ close acquaintance Daniel Wheeler, a Quaker missionary, had recently returned to England, taking with him casts of the Truganini and Woureddy busts. Addressing a cousin in Sheffield, Hannah Law writes:

‘… no doubt our dear friend D.Wheel[er] has arrived in Sheffd we have spent many pleasant hours with him here … he is accompanied by the Black Lady and Gentleman Wouraddy and Trucaninny I hope they will meet with a courteous reception from the Cutlers company I assure you I have a great respect for them Trucaninny has often sat on the carpet at my feet and sung to me while I was working then she would say shuppe wine Missie Law I would give her a glass she would sing again, then shuppe wine I would say no Triggy you’ll be ill, O you ugly Ole woman she would say very well Triggy go away don’t expect any thing from me again then she would cry O you vary nice lady Messa Law fine fellow …’12

Here we catch the echo of Truganini’s negotiating skills in action. In concrete form, we see the abstract ‘agency’ that is such a staple of contemporary historical jargon. Truganini is observed maintaining her cultural identity through song, offering that song to Hannah Law, demanding a reciprocal gift in the form of a glass of wine, becoming angry and insulting when denied a second glass, and then, when threatened, backing down and schmoozing up. This is a real person, and, even through the creole speech, a pretty canny operator. If we imagine Truganini only as the Last Tasmanian Aborigine, as the grizzled, overweight old lady terrified by the certain prospect of her posthumous mutilation, we lose touch with the vitality of this young woman’s resistance.

The young Truganini would not be constrained. She seized the opportunity to escape the Flinders Island detention centre by accompanying Robinson to the Port Phillip district in 1839. When she and a number of her compatriots turned bushranger, she was undoubtedly complicit and may even have been the initiator of the consequent killings, thefts and arson at Cape Patterson on Westernport Bay. Her young male companions, Peevay and Timme (aka ‘Bob’ and ‘Jack’), were tried, sentenced and hanged for murder, the first executions conducted in Victoria under British law. Truganini escaped the gallows on that occasion, but never forgave Robinson for what she evidently considered his abandonment of the Palawa. She was to cut him dead when he visited Oyster Cove in 1851.13

In Melbourne, 2009, in response to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre protests and in consultation with the owners of the works, Sotheby’s withdrew the Benjamin Law portraits from sale. Nala Mansell-McKenna, Secretary of the Centre, said the plaster busts should be returned to Tasmania, where a community meeting would decide their fate. In a subsequent letter to the eleven museums that hold casts in their collections, Ms Mansell-McKenna wrote: ‘Aborigines find it offensive that images of our dead are still being used without permission. We now write seeking agreement on what items can, or should not, be displayed.’

It is at this point that I take offence. I certainly strongly endorse the necessary courtesy (or simple precaution) of keeping secret-sacred Aboriginal material from inappropriate public view. I can readily accept the indigenous perspective that human remains should not be put on display and should, if possible, be returned to their descendants and laid to rest in their country. However, the proposed censorship of secular images I can neither understand nor sanction. For a start, there are not so many such pictures that we can afford to lose sight of any of them. Moreover, the suppression of images is plain silly, both impractical in the age of the Internet and simply wrong in terms of the evolution of Aboriginal culture since 1788. As Philip Jones has observed in his account of ethnographic photography in South Australia: ‘It is ironic … that more than two centuries after traditional attitudes towards images began to loosen, reflecting a dynamic series of shifts and revisions within Aboriginal societies, Australian cultural institutions and television channels began adopting restrictive access protocols towards Aboriginal imagery.’14

Most importantly, though, restriction is wrong because all works of art containing images of Aboriginals that have been made by settler artists since Europeans first explored, invaded and occupied Australia, whether sketched, drawn, painted, carved, modelled, caricatured or designed (and even written, sung, acted, danced or filmed), are necessarily, by definition, documents of coexistence, of a shared identity of place and, later, of nation. They may well document oppression of Aboriginal people in what they depict or in the manner of the depiction. They may describe or embody or have had attached to them profound misunderstandings of traditional and developing indigenous cultures. But they are, in the end, undeniable, irreducible historical objects, necessary vehicles both for understanding the past and for constructing the future.

For me the most difficult and disappointing aspect of the affair of the Benjamin Law busts was therefore the response of the art-historical and curatorial establishment. An editorial in the Hobart Mercury sensibly observed that ‘it would be better to change people’s perception of [Truganini’s] place in history, not try to banish her image’, and, in the Australian Art Sales Digest, Aboriginal art consultant Jane Raffan likewise called for cultural institutions to ‘actively investigate the historical context of [the busts’] production’. There were also a handful of letters to newspapers and sundry blog posts, but the only extended analyses of the fracas were by the conservative columnists Christopher Pearson, in The Australian, and John Izzard, in Quadrant, who seized the opportunity to lambast ‘new-think culture’, ‘gesture politics’ and the ‘ultra-left Aboriginal fringe’.15 But from the academics and curators whose daily professional practice depends on access to images, artefacts and works of art, not a word.

I think I know why. For the academics, the affair was not a debate to become involved in, but a cultural phenomenon to observe. A post-colonial conflict, an ‘iconic’ image, political party involvement, an art market angle, the Aboriginal flag, gender binaries – such are the materials of contemporary art history. What’s more, it was all readily available on the Internet, without any need to look up obscure articles in the Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, let alone to pursue primary sources such as Ross’s Hobart Town Almanack and Van Diemen’s Land Annual for 1836, or, dare I suggest, to examine closely the works themselves. I await the inevitable Cultural Studies conference paper with interest. For the museum directors and curators, to be perceived to be defending the buying and selling of works of art against the strongly expressed wishes of an indigenous organisation would probably entail a risk of loss of confidence from their various Aboriginal constituencies and, more practically, potential disruption to their own delicate, sensitive ongoing negotiations with regard to Aboriginal collections past, present and future.

‘if reconciliation is to get any real traction in this country, it must be based on demonstrable empirical truths, it must be about particularities, about individuals’

This is simply cowardice and evasion. I know, because it is precisely the same cowardice and evasion I myself displayed not so long ago with regard to The Picture. Nobody wants to stand up to people whose land was stolen, whose ancestors were murdered, whose children were taken away, whose life expectancy is twenty years less than that of the rest of the Australian population and say: ‘No, sorry, mate, you’re wrong about this one.’ But if reconciliation is to get any real traction in this country, it must be based on demonstrable empirical truths, it must be about particularities, about individuals. It will not be achieved by silent acquiescence to misguided enthusiasm, or by ambit claims and politically correct slogans, which simply provide ammunition for the culture warriors of the right.

The story and the imagery of Truganini of the Nuenonne from Lunawannaloona provide an object lesson to those who practise ideological art history and museology, to the purveyors of postmodern platitudes. The people who inhabit the Abiding are every bit as difficult as the living. They cannot be constrained by intellectual postures or fashions, only by the material and documentary truths of their lives and deaths. It is a primary responsibility of non-indigenous historians to uncover and interpret those truths, and to offer them back to Aboriginal Australia. It is our profession’s way of paying the rent.

We shouldn’t expect any thanks. We have seen how a close address to the Benjamin Law bust gives us Hannah Law’s letter and through it Truganini’s voice. Truganini also speaks through the works of Annie Benbow, a Tasmanian settler woman who grew up at Oyster Cove in the 1840s, whose family knew the Palawa well as neighbours and who accompanied Truganini on a visit across the Channel to her Bruny Island home. Late in life, Benbow made a number of remarkable drawings of the Oyster Cove establishment, based on her childhood memories. One of these drawings is in the collection of the TMAG, and amidst its frieze of hunting and feasting Palawa and their dogs, there is the irrepressible Lalla Rookh, climbing up a tree. Pursuing this picture and its artist, I was made aware of an obscure article in The Lone Hand of June 1913, in which the author recounts an interview with Benbow and her recollections of Truganini.16 Here, hidden within or behind the art object, or at least tracked and accessed through that object, is something not found in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s Aboriginal display case: a small piece of missing history, of raw vengeance, of the very spirit of resistance.

One of the old Queen[’s] stories ran as follows: a white man was burning oyster shell on the Brune [sic] shore. A black man crept up and speared him and the wounded man ran some distance with the spear through his body before he fell down and died.

Just look at those eyes. Truganini can take care of herself.

Endnotes

1 Dan Sprod (ed), Victorian and Edwardian Hobart from Old Photographs, John Ferguson, 1977.

2Andrew Sayers, Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century, OUP in association with the National Gallery of Australia, 1994, pp 1–4.

3 Paul Fox and Jennifer Phipps, Sweet Damper and Gossip: Colonial Sightings from the Goulburn and North-East, Benalla Art Gallery, 1994; Tom Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors: The Antiquarian Imagination in Australia, Cambridge University Press, 1996; John Jones, The Wares, Mopors, Robert Dowling and Eugene von Guérard in the Western District of Victoria in the 1850s, National Gallery of Australia, 1998; Philip Jones, Ochre and Rust: Artefacts and Encounters on Australian Frontiers, Wakefield Press, 2007; John McPhee, Joseph Lycett: Convict Artist, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 2006.

4 These identifications were recently confirmed when the wax lining of the painting was removed, revealing notations by Dowling himself. Additionally, the seated figure on the left is denominated ‘Jinny/West Coast/VDL’. My thanks to Michael Varcoe-Cox, Helen Gill and Humphrey Clegg for kindly showing me the work during the course of its conservation treatment.

5 The Shadow of The West (Producers Colin Luke and Geoff Dunlop; Director Geoff Dunlop; Writer/narrator Edward Said), Part 7 of the 10-part Landmark Films series The Arabs: A Living History (1979–1983).

6 Quite literally, in some cases. See, for example, Jeanette Hoorn’s confusion of the Blue Mountains’ Bathurst (Apsley) and Wentworth (Weatherboard) Falls, in Australian Pastoral: The Making of a White Landscape, Fremantle Press, 2007, p. 42.

7 John Lhotsky, ‘Australia, in its historical evolution’, The Art Union, July 1839, pp 99–100.

8 Robert Drewe, The Savage Crows, William Collins, 1976; Bernard Smith, The Spectre of Truganini, Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1980; Gordon Bennett, Requiem, oil on canvas, 120 x 120 cm, coll: Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane; Midnight Oil, Truganini, Columbia Records, 1993.

9 Michael Mansell, interviewed on P.M., ABC Radio National, 24 August 2009.

10 Michael Mansell, quoted in Christopher Pearson, ‘Works of art pressed into another service’, Australian, 29 August 2009.

11 Hobart Town Courier, 7 October 1836.

12 Letter, Hannah Law to Thomas Ellin, 22 May 1838, in Paul Paffen and Margaret Glover, ‘The Hannah and Benjamin Law Letters’ in Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol. 45, no. 3, September 1998, p. 178.

13 An account of the Port Phillip District episode was presented on Hindsight, ABC Radio National, 8 February 2009.

14 Philip Jones, ‘Ethnographic Photography in South Australia’, in Julie Robinson and Maria Zagala, A Century in Focus: South Australian Photography 1840s–1940s, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2007, p. 105.

15 ‘Seeing the Real Picture’ (editorial), Mercury, 25 August 2009; Jane Raffan, ‘Withdraw the Benjamin Law Busts? A Contrary View’ in Australian Art Sales Digest (online edition) 23 August 2009; Christopher Pearson, op. cit.; John Izzard, ‘Return of the Culture Wars’, Quadrant (online edition) 31 August 2009.

16 Annie Benbow (1841–1917), Aborigines and Settlers at Oyster Cove in 1847, pencil on paper, 50 x 72 cm, coll: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery; James Hebblethwaite, ‘Mr C. Benbow’s Fruitful Land’, The Lone Hand, 2 June 1913, quoted in Eve Buscombe, Portraits of the Aborigines, Eureka Research, 1980 (n.p.).