- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bathroom tiles

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

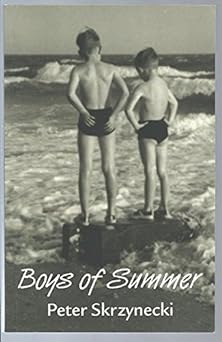

A generation of Australian schoolchildren knows Peter Skrzynecki’s poetry. The simple, direct language of Immigrant Chronicle (1975) speaks of both the desolation and optimism of the postwar migrant. Boys of Summer, Skrzynecki’s third venture into book-length fiction, treads similar thematic terrain.

- Book 1 Title: Boys of Summer

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $26.95 pb, 222 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

More disturbing is the new curate in the local parish, Father John, who takes an unusual amount of interest in Tom and his friend Paul, both altar boys. Father John ingratiates himself with Tom’s parents and offers to take him on outings: ‘He’ll be perfectly safe, I can assure you. Trust me. I’ve also asked Paul’s parents and they have no objections to any of my proposals: the Easter Show, the beach or even the pictures ... For boys of this age going out is good for their mental and physical development. And of course I’ll keep an eye out for their spiritual growth as well.’ It is hard to accept these days that anyone would fall for that, but the parents in their innocent trust of priestly authority readily agree. Tom is not so sure. Even so, nothing much happens for some time, apart from searching glances and hair-ruffling.

Skrzynecki’s spare, unadorned style suits his poetry, but in prose it tends to plod, and in Boys of Summer tedium sets in early. ‘Tom’s favourite program was Superman, played by George Reeves. Superman could fly through the air, bend steel with his bare hands, was faster than a speeding bullet and more powerful than a locomotive. He had come to Earth from the exploding planet Krypton ...’

Yes, I think most people from the planet Earth are already familiar with the talents of the mild-mannered Clark Kent. And also with the excellent qualities of Tom’s favourite comic-book character, ‘The Ghost Who Walks, The Man Who Cannot Die’, who ‘lived in the Skull Cave in a jungle with the Bandar, the Pygmy Poison People ...’

Reading Boys of Summer, I had to keep reminding myself that it was a novel, not a memoir. We are regaled with the particulars of local shopkeepers and the name of the milkman’s Clydesdale (but not, for some reason, the baker’s, perhaps because the Krupas usually bought their bread from the Greek delicatessen instead). The life he describes might have been pleasant to experience, but it is deadly dull to read about. ‘The tiles in the Krupa bathroom were pink, blue and grey, while the fibro walls had been painted green and pink.’ The expedition to choose a puppy for Tom is described in excruciating detail. The mother of the litter belongs to a family of friends, but Tom picks out the very puppy that Lech, a boy his own age, wants to keep, and a tantrum ensues. Usually in a novel something like this would lead somewhere, but there is no sequel – we hear nothing more about Lech.

Occasionally, Skrzynecki gets preachy: ‘When he grew into adulthood, Tom realised that these days had been among the best of his life. Not only was he with his parents, but he still had those links to his identity which, although they sometimes made him feel different and self-conscious with other children, ultimately helped define his place in the world.’ That may be so, but this does nothing to develop the story or to keep the narrative ticking along.

The imagery is often strange, as if this professor of English doesn’t quite understand how similes work. Father John drives a Volkswagen, which sits by the kerb ‘like a giant beetle’. He drives the boys down the coast ‘through places with names like Waterfall and Heathcote’. Surely the names are not like Waterfall and Heathcote, but are Waterfall and Heathcote? Humour is rare, so it is hard to know whether the parting remark of a doctor visiting the family after a tragic event is supposed to be a joke: ‘You have a lovely home, by the way. Beautiful curtains. Did you buy them at David Jones?’ he asks. In a different book this could be wryly absurd. In Boys of Summer it is just puzzling.

Reading this book about these nice people living very ordinary lives is a disturbing experience. When nothing much happens for such a long time, you long for some dramatic event. You don’t really wish to visit sexual abuse, mental illness or violent death on any of them, but the reader is a restless, easily distracted creature. Had I not been asked to write this review, I wouldn’t have made it past the bathroom tiles on page thirty-eight.

Comments powered by CComment