- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘A very self-examining man’

- Article Subtitle: The long-awaited second volume of Eliot letters

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first volume of T.S. Eliot’s letters, published in 1988, covered his early life to the end of literary modernism’s annus mirabilis, 1922. The year was a turning point in the thirty-four-year-old Eliot’s career. In November he published the poem that made him famous, ‘The Waste Land’, in the inaugural edition of Criterion, the journal he was to edit until 1939.

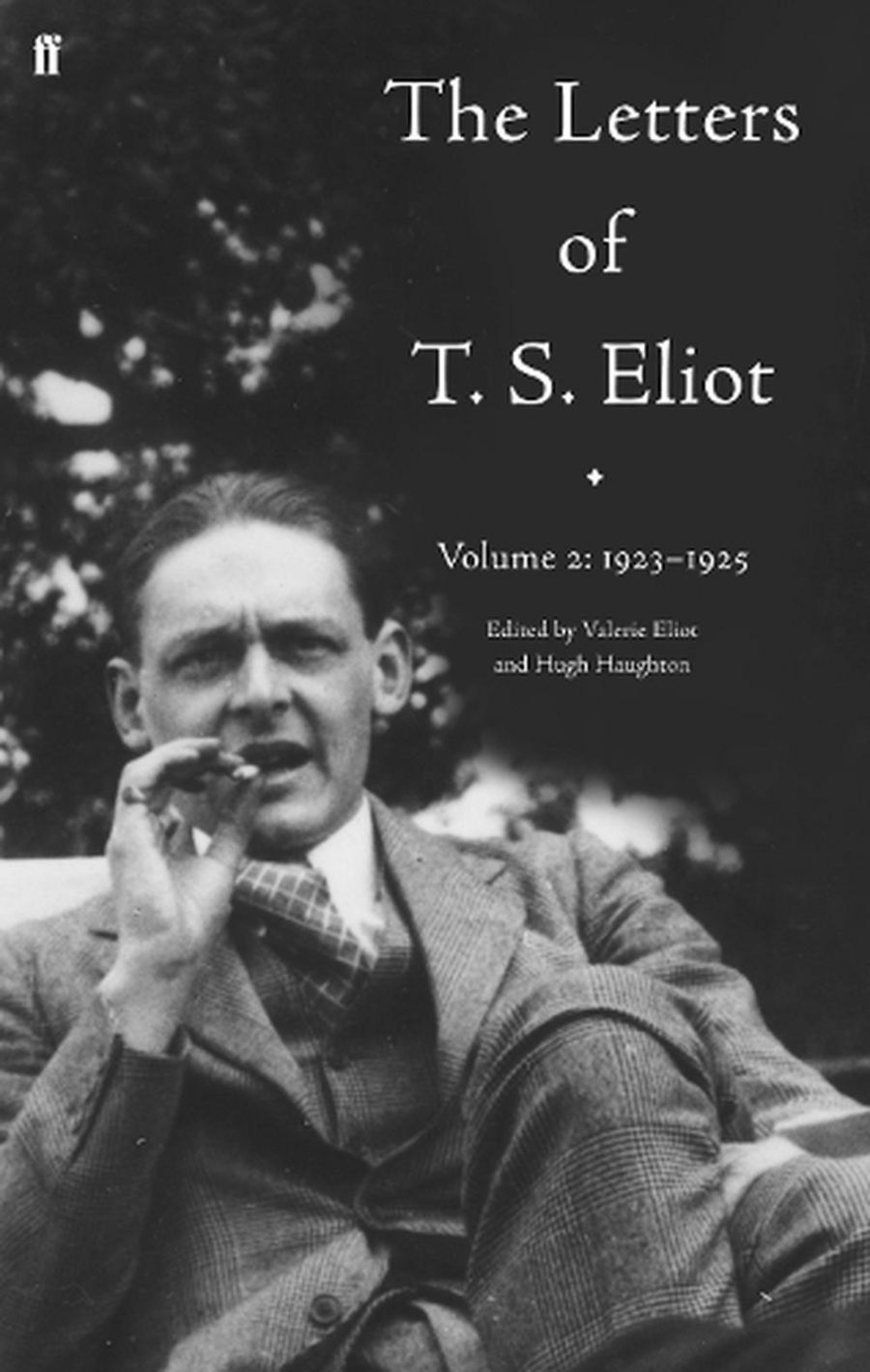

- Book 1 Title: The Letters of T.S. Eliot, Volume 2

- Book 1 Subtitle: 1923–1925

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber and Faber, $89.99 hb, 909 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Eliot’s life in the early 1920s was frequently miserable. His overhasty marriage to Vivienne Haigh-Wood in 1915 was a disaster from the start. It quickly became apparent that the instinctively reserved Eliot, who once confided to Virginia Woolf that his greatest fear in life was humiliation, was temperamentally mismatched with his vivacious wife, who promptly cuckolded him with Bertrand Russell. Furthermore, Vivienne was almost constantly ill. From the day of their wedding there is hardly a personal letter in Eliot’s published correspondence that does not allude to her fragile health.

The strain of working full-time at Lloyd’s Bank, while juggling various writing commitments and caring for his wife, drove Eliot to a nervous breakdown in Autumn 1921. Three months’ leave from Lloyd’s gave him time to write ‘The Waste Land’, but as soon as he was back at work things picked up where they left off. Indeed, Vivienne’s health crises reach something of a climax in 1923, when she is laid low with migraines, colitis and what Eliot variously describes as enteric, septic or malignant influenza, accompanied by a risk of appendicitis or peritonitis. Several times he refers to her condition as being near-fatal. He was more or less permanently on the brink of exhaustion. His job at the bank, he observes in one letter, took up forty-four hours of his week. In addition, he was editing Criterion almost single-handedly, for no money. The journal, he informs the poet Harold Munro in May 1924, ‘is run without an office, without any staff or business manager, by a sickly bank clerk and his wife: the latter has to be on her back half the time and the former has conducted all his work in the evenings in his own sitting room, after a very busy and tiring day, and subject to a thousand interruptions: without even a desk until he bought a second hand one at Christmas!’ His health gave out again in early 1925, when he was struck down with a serious bout of influenza. Not to be outdone, Vivienne promptly collapsed again in March, with bronchitis, neuralgia and rheumatism of such severity that it baffled all medical opinion. By June she had developed a serious liver disorder. Eliot was not writing a lot of poetry.

The volume’s bulk is explained by the fact that it is largely concerned with the day-to-day business of editing Criterion. It is filled with letters cadging contributions, tactfully rejecting unsolicited articles, chasing up stray commissions, and so forth. Some of this is mundane, but it is not uninteresting. The insights these letters provide often have less to do with Eliot’s poetry or his private life than with his understanding of his role as an editor and critic. In an early editorial titled ‘The Function of a Literary Review’, Eliot declared that his ambition was ‘to maintain the autonomy and disinterestedness of literature’. He saw Criterion as an élite journal and was indeed successful in keeping its circulation below one thousand throughout its seventeen-year existence. Contributors were wooed with the argument that Criterion ‘aims solely at publishing the highest class of work. While a contribution to this paper does not reach a very large audience, it probably receives more intelligent critical attention than a contribution to any other review and its audience is not limited to Great Britain.’

This commitment to the ideals of disinterestedness and lofty literary standards did not preclude the journal’s reflecting, in an indirect way, Eliot’s personal opinions. He described himself as ‘an old-fashioned Tory’, whose political and social views were ‘reactionary and ultra-conservative’. He conceived of Criterion as being ‘apart from current political controversy, that is independent of party politics, and leagued with an ideal rather than with the actual Tory party’; it was to be ‘a Conservative review which is founded rather on Aristotle than on the views of Viscount Younger’. In an exchange with Herbert Read, one of Criterion’s regular contributors, Eliot writes of assembling a ‘phalanx’ of like-minded writers: ‘what is essential is to find those persons who have an impersonal loyalty to some faith not antagonistic to my own.’

Eliot was later to become a venerable public figure and a hugely influential literary arbiter, but he was, at this time, still a writer whose reputation was only well-established in literary circles. Included in the volume is a letter from the publisher of his first collection of critical essays, The Sacred Wood (1920), dryly informing him that demand for his book is ‘not very good’. In this context, his high-minded ambitions can seem at once vast and unreal. Eliot does not give the impression of a man whose mind was much exercised by the realities of politics. In an obsequious letter to the French reactionary Charles Maurras – from whom Eliot was later to borrow his famous summation of his ‘general point of view’ as ‘classicist in literature, royalist in politics, and anglo-catholic in religion’ – he declares that Criterion is ‘engaged in working out a general philosophy which will exert a gradual influence on politics, theology and literature’.

A similar airiness would seem to apply to Eliot’s anti-Semitism, which has been hotly debated since the publication of Anthony Julius’s adversarial study T.S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism and Literary Form (1995). Eliot does make the occasional sneering aside, and in one letter he notes his faint distrust of Disraeli on racial grounds, but these unworthy sentiments are too infrequent to suggest he was consumed with hatred. His opinions were snootily anti-democratic and, in certain respects, rather unpleasant, and he deserves to be pilloried for some of his public statements, but there is little in these letters to support Julius’s claims about the centrality of anti-Semitism to Eliot’s literary practice.

The evolution of Eliot’s political and literary views during this time and the tension between his private struggles and his public self are revealed in his curious relationship with the critic John Middleton Murry. Publicly, the pair were antagonists. In the early 1920s they were arguing with each other in the pages of Criterion and Murry’s rival publication, the Adelphi, about the relative merits of Romanticism and Classicism. Several years before Eliot’s religious conversion, Murry observed, rather astutely, that the direction of Eliot’s thought was leading him toward an embrace of Catholic dogma; for Eliot, Mr ‘Muddleton Moral’ represented exactly the kind of wishy-washy liberal humanism he most despised: ‘everything Murry believes is anathema to me,’ he wrote to Frederic Manning; ‘I have never found any writer whose views were so antipathetic to me.’ Nor was Eliot enamoured of Murry’s first wife, Katherine Mansfield, whom he derided to Ezra Pound (they tended to bring out the worst in each other) as a ‘persistent and thickskinned toady’ and a ‘sentimental crank’: ‘her inflated reputation,’ he told Richard Aldington in 1923, ‘ought to be dealt with’.

Yet the two men remained cordial, with Murry in particular keen not to let their philosophical differences stand in the way of friendship. Eliot’s letter in February 1925, thanking Murry for arranging a series of lectures at Cambridge on his behalf, expresses sincere gratitude, describing the gesture as ‘a ray of hope just at the blackest moment of my life’. And it is to Murry that the volume’s most searching letter is addressed. Written in the dark days of April 1925, it begins abruptly:

In the last ten years – gradually, but deliberately – I have made myself into a machine. I have done it deliberately – in order to endure, in order not to feel – but it has killed V. […] I have deliberately killed my senses – I have deliberately died – in order to go on with the outward form of living – This I did in 1915. What will happen if I live again? ‘I am I’ but with what feelings, with what results to others – Have I the right to be I […] Does it happen that two persons’ lives are absolutely hostile? Is it true that sometimes one can only live by another’s dying? […] Must I kill her or kill myself? I have tried to kill myself – but only to make the machine which kills her.

Woolf thought Eliot a ‘very self centred, self torturing and self examining man’. But there is relatively little of this side of him revealed in his letters. Even when he is complaining about his lot, he tends to retain a certain poise. The genuine sense of desperation and the lacerating guilt expressed in the letter to Murry are striking for their incongruity. The fractured sentences, broken by dashes, are highly uncharacteristic.

Much of Eliot’s mystique derives from this emotional guardedness, which gives him a slightly elusive quality. He strongly rejected the idea that poetry was a directly confessional mode of expression. He argued that it had its source in the poet’s emotions, but that in rendering his emotions as poetry, in finding an appropriate form, the poet objectified them, extinguishing his own personality in the process. The emotion and sincerity in his verse tends to be masked by his disjointed technique and his sense of poetry as a dramatic medium, which refracts its expressive purpose through a range of voices and ironic personas, from Prufrock to the stranger in ‘Little Gidding’ who emerges from the darkness to disclose the melancholy ‘gifts reserved for age’. He often uses what his biographer Lyndall Gordon describes as ‘a confessional strategy useful to a cautious and shy sensibility: to dramatise his most serious ideas as irrational, even ridiculous’. In his critical writings, too, he frequently wears the mask of an ironist. These letters are a valuable resource. They tell us a great deal about Eliot. But they also hint at just how much we will never really know about Old Possum.

Comments powered by CComment