- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: No smoking gun

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Colin McLaren has already published two books drawing on his own remarkable experiences as an undercover policeman – On the Run (2009) and Infiltration: The True Story of the Man Who Cracked the Mafia (2009) – the former a work of fiction, the other autobiographical. In this latest work he merges the two forms to create a biographical novel of his beloved grandfather George Bingham, who, with a few mates, was among the first to enlist, in an Anzac battalion filled from rural Victoria within a fortnight of war being declared.

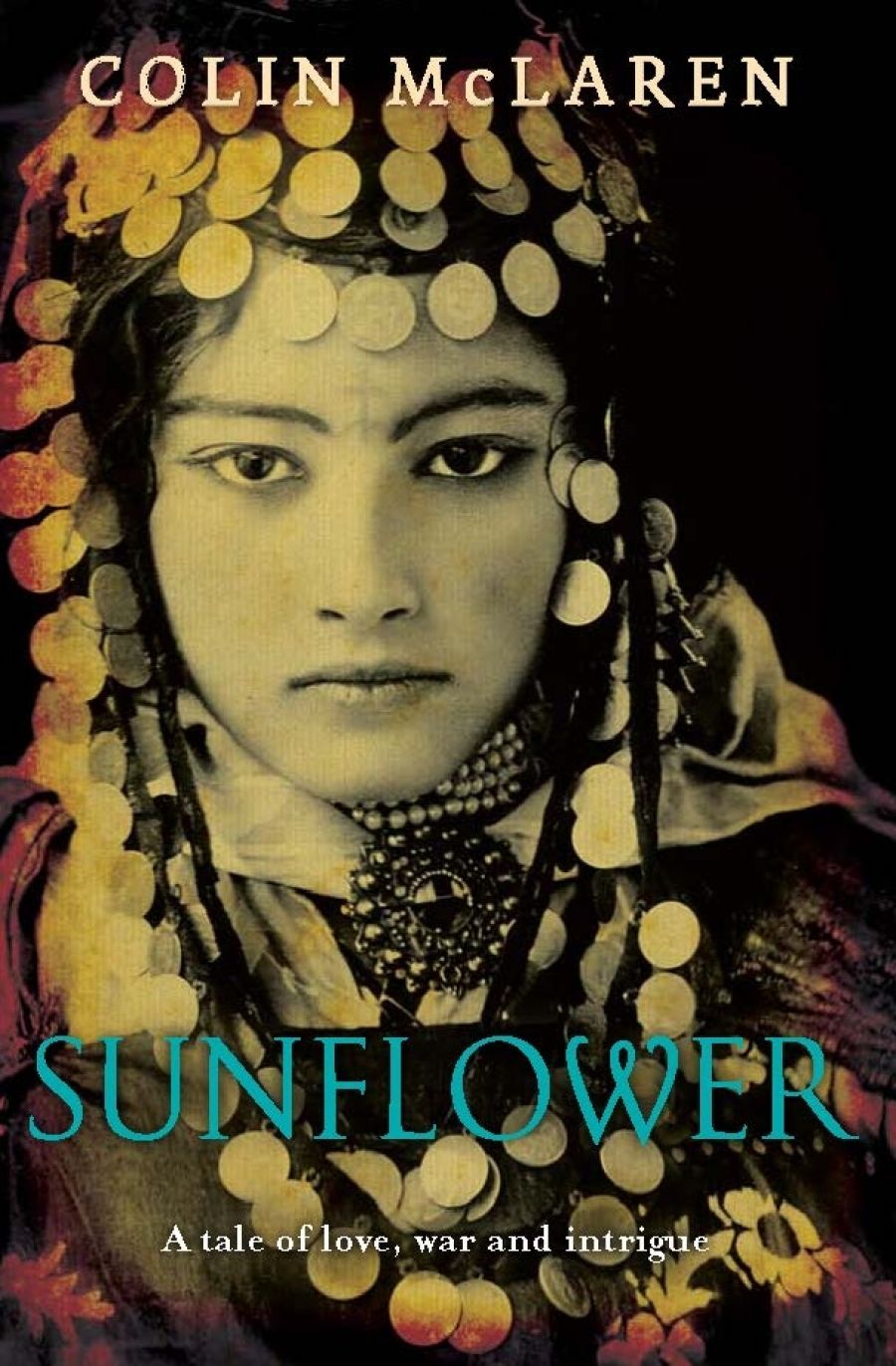

- Book 1 Title: Sunflower

- Book 1 Subtitle: A tale of love, war and intrigue

- Book 1 Biblio: Victory Books, $32.99 pb, 295 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

There can be no making sense of what was utterly senseless. Those men were where they were, keeping their head down, coping as best they could with the conditions, scrounging for water and ammunition, and occasionally getting some sleep (even that had its hazards). It is familiar material, from fiction and from history. How, then, to find a way of presenting it in a fresh manner, and to provide a new perspective?

The ghost of C.E.W. Bean hovers over many such accounts. He makes an invented cameo appearance here, not entirely successfully; just one example of McLaren’s choosing to present history as a novel. McLaren tries his hand at writing in General Monash, too, bungling his first assignment at Gallipoli, then comfortably ensconced in a French château. Even more unsatisfactorily, Squizzy Taylor also gets into the story, a creepy little toad (he may have been George’s de facto brother-in-law).

The function of these historical silhouettes should be to shore up the sense of actuality; but curiously the effect is just the opposite, because the big-name players are diminished by being brought down into the common narrative. Bean is a pompous ninny who tells the generals the bleeding obvious. Monash is a latter-day Mark Antony, unable to leave his plump mistress. It takes a different order of fiction to reconstruct the complexity of such figures. They cannot be drawn as simple figures in ordinary scenes without in some sense becoming caricatures. On the other hand, the writing depends on the weight of those figures to do its work for it.

That is a danger for the lesser figures, too, though for a different reason. In such familiar material, it can be difficult to escape typecasting or to construct characters who are individuals, if not unique. For example, one of George’s mates, the unfortunately named ‘Dimples’, who is forever running messages up and down the trenches, is inescapably reminiscent of Archie Hamilton in Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli. But he doesn’t turn into anything, or become anyone.

There are more considerable possibilities for George, however, not only because he is at the centre of the narrative, but also because we first meet him as the person he has become, a discerning old man with innate tact and practical wisdom, one who has learned from his past, and learned to value what he has. He presents as a man worth listening to and knowing.

This is only one part of the tale McLaren tells. A more promising theme has to do with the lurid subtitle, with its hint of the darkly exotic. In Cairo, just before the troops were sent off to Gallipoli, George had his coffee cup read by a beautiful Bedouin fortune teller. The fact of her stunning beauty is wholly irrelevant, except to whoever wrote the subtitle and designed the cover. This pitch to the cheaply seductive is a miscalculation, because she hints at something altogether more profound.

The fortune teller and her people are acknowledged as having remarkable prophetic skill. They are not just gypsies; they have arcane knowledge. They can interpret the symbols of the old scriptures. She warns George to beware of dangerous dark water; that he will see a heroic warrior (who turns out to be Mustafa Kemal Atatürk); and that he will meet death four times. He starts counting off the episodes of course, as you would, and returns to her for further clarification, hoping for reassurance. Which opens up an entirely new line of thought, about how things come about, and what fate holds for us. George, a man who reads and thinks, has noted that great figures from the past, Alexander, Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, went to Cairo to discover from the Pharaonic scriptures what their future held, just as in his own more modest way, he has. That theme could have evolved into an engaging set of reflections about war and its fatal senselessness, and individual destiny, and ancient curses and coincidence, and the whole shooting match. It puts matters into perspective. This most recent war is, after all, just one more in an unrelenting series.

McLaren writes with enthusiasm and affection, but he hasn’t explored all the possibilities of his material. His grandfather had a deeper sense of the mystery of things; but he doesn’t do the telling. It is all there, waiting to be realised.

Comments powered by CComment