- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Making nooky

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The cover-blurb is a genre all its own. No sensible publisher would grace the cover of a book with the assertion, ‘This is a pile of crap’, even if it is. So we should all take a blurb cum granum salis. The blurb for John Dale’s Leaving Suzie Pye reads: ‘Rips along with verve and confidence … funny, energetic and full of life.’ The signatory is Helen Garner. Can this be the same Helen Garner who gave us The Children’s Bach and The First Stone, I asked myself, as I persevered with Dale’s lacklustre novel. What significant omissions are concealed behind those three periods in her remark?

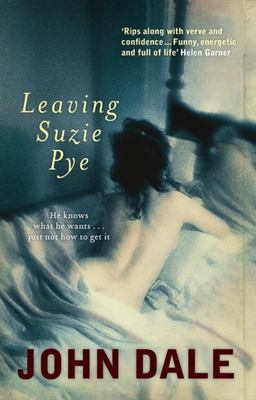

- Book 1 Title: Leaving Suzie Pye

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $27.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

The blurb claims that Leaving Suzie Pye ‘examines the nature of lust, love, ambition and what it means to be a man’. Well, not this man, though I admit to being a generation older and perhaps wiser than Dale’s protagonist and privileged first-person narrator, Joe Ray. It is not Dale’s fault, and comparisons may be odious, but I have in recent weeks been immersed in the Collected Stories of John Cheever. Now there is a writer who understands the complexities of ‘what it means to be a man’. Cheever’s story ‘The Country Husband’ is preoccupied with similar concerns to those of Leaving Suzie Pye, and its last lines have an epiphanic upbeat similar to Dale’s; but consider the difference in management of tone, in articulation of significant detail. Unlike Cheever, Dale’s serious purpose – and there is one, I am convinced – is compromised by his fantastical and ever-radiating narrative.

Leaving Suzie Pye, a story narrated by the priapically obsessed Joe Ray, with its eponymous heroine, who is so annoying, to this reader if not to Joe, as to seem a caricature of every aspect of institutionalised feminism and meliorism, may be an instance of antipodean picaresque, not to be taken too seriously. It begins, in an updated version of Maupassant’s ‘Cemetery Walkers’, in Bunnings at Mascot, moves to the UTS tower, that paradigm of brutal architecture, where Joe works in a lowly non-academic job, to the Broadway Centre, then, because of Joe’s legacy from his late bankrupt barrister father, to Turkey, the Hellespont, Gallipoli and Istanbul, where Joe is mugged.

Back home, he is run down and grievously injured by a black Commodore, is declared clinically dead, revives, is hospitalised, emerges in time to attend the Dawn Service in Martin Place in the rain with his daughter, and ends at Broadway in a most undeserved upbeat ending, when he looks up ‘at the half moon nailed firmly beneath the Southern Cross, and [feels] blessed’.

The plot of Leaving Suzie Pye recalls the outrageous and politically incorrect novels of Ross Fitzgerald, such as All About Anthrax (1987) and Busy in the Fog (1991), though Fitzgerald’s hero Grafton Everest makes Dale’s Joe Ray look every bit the SNAG. The problem is that Suzie Pye is herself so irritating as to make all of Joe’s ridiculous adventures seem justified. Thus Joe begins a liaison with the beautiful, tattooed Athena on an aeroplane when he reads the following over her shoulder from her book:

At that moment I felt the walls of her pussy close on my penis. I felt as though I was disappearing into space, only my penis was alive, a wave of extra-ordinarily intense pleasure coursing through it. I ejaculated lengthily several times … I could have died for such a moment.

That is Michel Houellebecq, as she informs him. The consummation Joe devoutly wishes is a long time coming, and its results are disastrous. Improbabilities accumulate as the novel proceeds.

‘Why does lust fade so easily? Where does it go?’ are questions the novel asks but doesn’t satisfactorily answer, perhaps because Joe would appear never to cease to lust after Suzie, after Athena, then after Allison, his former wife, from whom he has been separated for ten years. It is a relief that his daughter escapes his lustful attentions. It is not that kind of novel.

His daughter ‘chatters inanely’ with him about the film Forgetting Sarah Marshall. That’s when the penny dropped for this reader. Leaving Suzie Pye belongs to a genre of novels and films beginning with a gerund, such as Robin Klein’s Hating Alison Ashley. Then there’s Jerzy Kosinski’s Being There, the Coen brothers’ Raising Arizona, not to mention the wonderful Henry Green’s novels Loving, Living and Party Going.

In the Istanbul bashing, Joe suffers a ‘broken carpal, two fractured ribs and concussion’, not to mention losing his cash, travellers’ cheques and passport. When the Commodore runs him down, he suffers a head injury, a broken leg, a fractured cheekbone, a ruptured artery and a heart attack. It is difficult not to believe he is being punished for something more than a night of nooky in Istanbul. Had his picaresque adventures continued, he might have come to resemble a character in Voltaire’s Candide, deprived of limb after limb after limb. It is his good fortune to be vouch-safed a terminal epiphany worthy of James Joyce, or John Cheever.

Comments powered by CComment