- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Perpetual elegy

- Article Subtitle: Bill Gammage’s enduring memorial

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

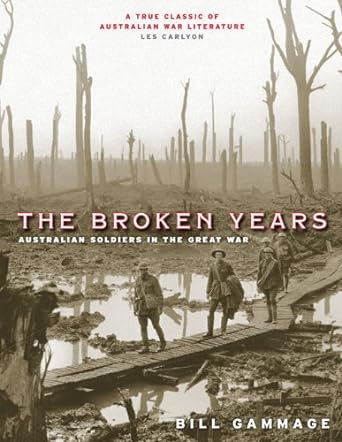

It is thirty-six years since the Australian National University Press published Bill Gammage’s The Broken Years; thirty-five since the unassuming Penguin paperback that became both a loved and critically acclaimed bestseller. Now Melbourne University Publishing has produced a deluxe, large-format, sombrely and evocatively illustrated edition. On the front cover is a Frank Hurley photograph of Australian troops crossing on duckboards a flooded field near the Menin Road in late October 1917. In the background stand stripped, gaunt, sentinel trees. Flip to the back cover and the image is of ‘A Young South Australian Patriot in 1916’. A cherub in uniform, he holds a toy rifle, in earnest for a conflict that, blessedly, will end before it is his turn to go.

- Book 1 Title: The Broken Years

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian soldiers in the Great War

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Publishing, $49.95 pb, 325 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Gammage’s book is avowedly not a military history of the First AIF, but ‘a study based on the diaries and letters of roughly 1,000 Australians who fought as front-line Australian soldiers in the Great War’. His narrative is woven from those materials, their stories, seamlessly framed and interpreted in Gammage’s own words. He writes not only of the men’s experience of war, but of the ways in which that illuminated ‘how Australians passed from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, on how the days of Empire gave way to the tradition of Anzac, and on how men came to be as they are in Australia’. Though this speaks of the future, Gammage’s tone here – as throughout the book – is elegiac. This is his memorable summary, in resonantly balanced cadences, of the Great War: ‘It engulfed an age, and conditioned the times that followed. It contaminated every ideal for which it was waged, it threw up waste and horror worse than all the evil it sought to avert, and it left behind legacies of staunchness and savagery equal to any which have bewildered men about their purpose on earth.’

Gammage’s prose needs this level of oratorical power (reminiscent of Manning Clark’s, but more restrained) in order to stand up to the impact of the photographs that transform this new edition. Here are men in their best suits solemnly taking recruiting oaths in the Melbourne Town Hall; others lying in a field, eyes bandaged after a mustard gas attack. There are staged, carefully lit photographs where art is more graphic than the actual and immediate. In the double-page spread that introduces Gammage’s account of the campaign in Egypt and Palestine, ‘The Last Crusaders’, Australian cameleers sit on their mounts in line of battle, early in 1918. In another, Prime Minister Billy Hughes rants without avail at a pro-conscription rally. The Broken Years covers so much material in a relatively brief compass. The credit is the author’s, as evinced in this succinct sentence chosen from so many: ‘On 24 April 1915, the first Australians who would fight in the old world were assembled on Lemnos Island.’

In this theatre of war, in particular, Gammage knows that Homer was there long before he was, but he too writes of terrible heroism and finds for it a language imbued with a sense of loss: ‘They clung while they could to notions of their immortality, but they came to realise that at any moment chance might stretch them alongside the still shapes about them.’ Gammage also canvasses less exalted material, never with a view to the exculpation of Australians (led by the partiality of his AIF sources, as nevertheless he must be). He describes the high incidence of venereal disease, the shameful riots at the Wasser in Cairo, the tiresomely sustained reluctance to salute British officers. He also subscribes to some long-held Australian notions of the ‘butchers and bunglers’ (as one popular account called them) of the general staff of the British army. Instanced are the withdrawal from Gaza after it had been taken by Australians and New Zealanders, Fromelles (‘Australians had never experienced a more calamitous or tragic night’), Second Bullecourt – ‘again a resentful remainder saw a British staff almost uselessly expend their fervour and valour’.

But Gammage is no tub-thumper. As always, he looks for the more enduring consequences of the Australians’ experiences of London, England, Empire and especially of the widely believed military deficiencies of the British. For most of them these were new experiences (if not for the significant percentage of the First AIF who were born in Britain). When he writes that ‘Many in the AIF never loved their country better than after they had left it’, Gammage remarks not only on pardonable anxiety and nostalgia, but the seeds of the parochialism that was so characteristic of the interwar years in Australia. To many of these men, England was ‘cold, crowded and corrupted by class divisions’. More important than that, ‘the war dealt the affections of Empire a mortal blow, and men never returned to the adulation of 1914’.

So many books – expansive or narrowly focused, polemical and populist – have succeeded The Broken Years that its eminence needed the reinforcement that this new edition provides. A number of those books – to name no names – also give ample evidence of the plagiarism of his work that Gammage protests against. Yet few have equalled his compassionate concision, for instance as he distils the fatalism of the members of the First AIF: ‘So they continued, grim, mocking, defiant, brave and careless, free from common trials and woes, into a perpetual present.’ Or consider these remarks in the chapter titled ‘The Outbreak of Peace’: ‘a world that had encased their lives and thoughts vanished, and a new world presented itself, a world bounded not by death and war, but by life and home.’ The lives of the returned servicemen and their families were not Gammage’s province (they have been finely analysed by Bart Ziino and Marina Larsson, in A Distant Grief: Australians, War Graves and the Great War, 2007, and Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War, 2009, respectively), but, typically, he still has astute comments to make: ‘They had become men apart, but this was their pride as well as their burden.’ The First AIF would earn many memorials – whether massive shrines or the solitary statues in country towns that speak so poignantly of the men’s separateness – but none finer or more fitting than Gammage’s The Broken Years.

Comments powered by CComment