- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Looking-glass war

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Do not be misled by the ‘Childhood Memories’ of the subtitle. Self-indulgent nostalgia is nowhere to be found in this book, which is a richly novelistic saga of a war-time family in Britain. It is Rodney Hall’s genius that his story evokes strong personal memories in the mind of the reader: in my case of a North Queensland childhood during the 1950s, punctuated by destructive cyclones and deadly marine stingers, rather than by German air raids. To read this book is a double pleasure: we enter both the world of young Rod and our own childhood at the same time.

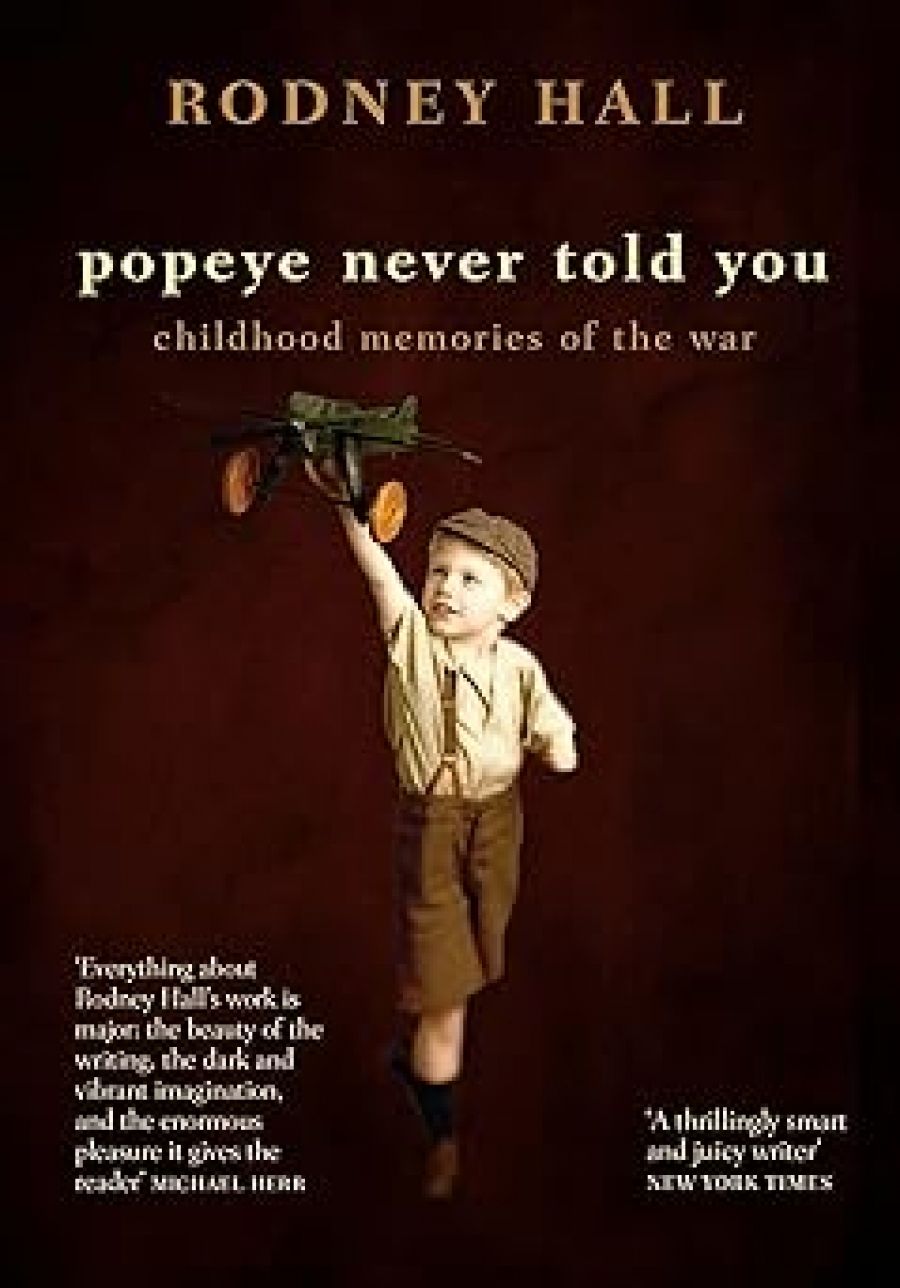

- Book 1 Title: Popeye never told you

- Book 1 Subtitle: Childhood memories of the war

- Book 1 Biblio: Pier 9, $29.95 hb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Occasionally throughout his story, Rod directly addresses the father he never knew but about whom he often thinks. ‘can yuo you see me from up in heven?’ he asks early on. Later, more practically, he wishes his father could give his older brother ‘a thrashing because even big boys cry if theyre hit hard enough’.

popeye never told you is divided into five chapters – 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 – which correspond with his ages and which also loosely chart the course of the war from 1940 to 1944. The main characters are Rod’s older brother, Mike, and his sister, Diana, as well as his mother and an assortment of official and unofficial aunts and uncles.

The first-person narrative is intriguingly punctuated with commas to mark the end of sentences, and no apostrophes at all. The only full stops come at the end of chapters and there are no capital letters except for names, though dialogue does have inverted commas. These literary ‘special effects’ are surprisingly powerful in creating not just the looking-glass world of the child, but also the child’s perspective on the puzzling and affronting world of adults.

The use of linking commas from sentence to sentence, and paragraph to paragraph, gives the story a beautiful slippery feel, allowing the reader’s own imagination easy play. The narration’s diminutive ‘i’ has an e.e. cummings scale to it, and the reader quickly adapts to the streamlined typography, as one does with Peter Carey’s equally brilliant, and largely unpunctuated, True History of the Kelly Gang (2000).

Hall’s boyhood story begins with the thrill of an air raid and the delicious terror of a five-year-old whose young life is so intensely experienced in the moments between each bomb: ‘… the enemy planes make the whole place shake, so i think its best to count to ten and i bet if theres not another bomb before ten we wont be hit and this could be the end of the war.’ The family of four crawl into an improvised shelter made by pushing a large settee against the piano. To take her children’s minds off the air raid, Rod’s mother, ‘Dods’, opens her special tin with photographs of the family farm back in Australia, at Kangaroo Valley.

As the youngest, Rod has a special bond with his slightly older sister, ‘Di’. ‘“we love the war!” we sing “we love the war!”’ Yet the fear of bombs and parachutists is ever-present: ‘Miss Wilkins calls me a dreamer only i dont like real dreams much because real dreams are mostly about men with guns stepping out of my bedroom cupboard.’

His considerable skills as a novelist enable Hall to convey deep emotion through his child’s-eye view, as when his mother rescues a couple of very young crying girls who are on their own in an air raid shelter:

she lifts one child on each arm and brings them back to us, and their shoes make smudges on her skirt and i try to point this out while they settle their heads against her shoulders and bury their grubby faces in her fur collar, just where i want to be, and they turn their eyes up to look at her.

One of the most memorable scenes occurs when the United States enters the war and Rod is in an excited crowd watching a convoy of American soldiers, who throw packets of cigarettes, chocolates and chewing gum to everyone: ‘“hi ya!” we yell and “okay buddy!”’ Dods later chides Rod for using such American slang. His favourite comic at the paper shop is Popeye, because he doesn’t put up with anything, ‘and he smokes a pipe and he has a tattoo and hes stronger than anybody and bashes them and thats what im going to be like’. These are not model children by any means. They spit on the cars below the windows of their flat, which is above a garage.

‘youre too little for spitting’ Mike says,

but i spit like a champion,

and if no cars come i aim at peoples hats instead,

Rod steals an Enid Blyton book from a bookshop, scribbles his name in the front and then decides to return it to the shop because he fears that Mike will expose him. The sequel to this is both unexpected and amusing.

Hall’s was a childhood without a house, a car, a proper backyard or even a bicycle. Or, of course, a father, to whom he secretly admits: ‘i only ever pretend to be good.’ Yet he also revels in having an adventurous brother and sister and a loving mother. When a lodger, forced on the family by wartime exigencies, makes unwanted sexual overtures to Dods, her children fly to her defence without quite knowing what is going on. Hall’s perfectly judged narrative perspective conveys both the children’s bewilderment and their anger.

One of the longest sections in the book is a Blyton-like adventure in an abandoned flour mill with echoing concrete walls. They discover tunnels and immediately become escaped prisoners of war. The vividly imaginative play also reveals much about the dynamics between young Rod, Di and Mike, the natural leader.

Despite the family’s difficult circumstances, Rod begins elocution lessons at the age of seven. For his eighth birthday, Rod receives a printing set from his Great-Uncle Mont, who says ‘what i look for in a boy is ink stains’ because ‘writing is the most important thing of all’. Unfortunately, the first word he prints is misspelled, something gleefully pointed out by his brother.

Despite his growing sophistication, dreaming of being Valentino in The Sheik, Rod is brought back to reality by his mother complaining about his grubby neck and dirty ears. Eventually, he picks up snippets of information about his father from Mike, who remembers visiting him in hospital.

The climax of the book is Christmas, complete with a tree ‘stolen’ from beside the railway line, and the wonderful thrill of waking up to stockings on Christmas morning. The end of the war in Europe brings wild celebrations but for Rod it is the mysterious absence, and yet tantalising presence, of his father that matters most.

I didn’t want this book to end. Like a good movie, it left me wanting the sequel where young Rod travels to a new life in Australia at the end of World War II. Readers of popeye never told you will be looking forward avidly to the next instalment.

Comments powered by CComment