- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Letters to the Editor

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Letters to the Editor

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Read this issue’s Letters to the Editor. Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Letters to the Editor

![]() Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

RANZCO and refugees

Dear Editor,

On 16 March 2022, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) endorsed an inaugural Position Statement on refugees. Entitled ‘Providing Equitable Access to Eye Health Care for Refugees and People Seeking Asylum’, the document was approved after nine months of deliberations. As an ophthalmologist, I was the paper’s lead author. RANZCO now joins fourteen other medical and nursing colleges in Australia with a policy on refugee health. On the one hand, we are a late addition to this group; on the other, we are the first surgical college to adopt such a position (while individual surgeons have spoken out, the Royal Australian College of Surgeons remains silent on this issue).

The Position Statement makes four key recommendations. One, refugees and people seeking asylum should be provided with access to comprehensive eye assessments. Most receive general health assessments on arrival in Australia, but eye health is not always included. Two, those that need it should receive access to eye-care services, such as glasses (optometry) or eye surgery (ophthalmology), irrespective of visa or Medicare status. Three, we do not condone mandatory, indefinite detention for refugees, especially children, given the detrimental health impacts of prolonged incarceration, and the pursuant risks to vision. Finally, we need to grow the evidence base on the eye health of refugees, an area that currently lacks research. Clearly, much work lies ahead.

RANZCO’s Position Statement was conceived in 2020– 21 during my time as ABR’s Behrouz Boochani Fellow. As such, a straight line can be drawn between an investment in the literary arts and the potential to improve people’s lives. The arts, in other words, can be an activator for humanitarianism. Thank you to Peter McMullin (who funded the Fellowship) and ABR; long may these investments continue.

Hessom Razavi, North Perth, WA

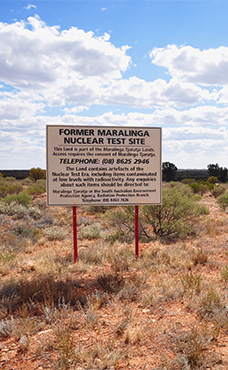

Black mist

Dear Editor,

Michael Winkler has written a sharp and insightful review of my latest book, The Secret of Emu Field: Britain’s forgotten atomic tests in Australia (ABR, May 2022). I am really glad to see his thorough and sensitive understanding of its story about the Operation Totem tests at the South Australian test site in 1953. He quite rightly wonders why I did not use the infamous quote about the Totem I ‘black mist’ from the British scientist Ernest Titterton, who was quoted in the media in 1980 following the first public disclosures of the phenomenon: ‘No such thing can possibly occur, I don’t know of any black mists ... The radioactive cloud is in fact at 30,000 feet, not at ground level. And it’s not black ... if you investigate black mist, sure your [sic] going to get into an area where mystique is the central feature and you’ll never be able to establish [it] or not.’

I had used part of this quote in my earlier book, Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga story, in the short section devoted to the Emu Field tests, so I made the decision not to reuse it in the new book. But I agree that it is a resonant quote, and one that points to Titterton’s dismissive attitude to any safety concerns around the conduct of British atomic tests in Australia.

Elizabeth Tynan, Alligator Creek, Qld

Eighteen up

Dear Editor,

Further to Faith Gordon’s argument about the disenfranchisement of sixteen-year-olds (‘The Case for Lowering the Voting Age’, ABR, May 2022), I would like to add that current sixteen-year-olds will not have a chance to vote federally until they are nineteen. In New South Wales they won’t vote in a state election until they are twenty-one. The statutory terms of Australian parliaments means that most people must wait well beyond the age of eighteen for their first chance to vote.

Retrieving Hemisphere

Dear Editor,

Steps are underway to enable the digitising of an important general interest Australian periodical from last century: Hemisphere – An Asian-Australian Monthly (later Magazine bimonthly), which was published by and for the Commonwealth of Australia from 1957–84. Some readers may recall the periodical, which was edited by two outstanding editors: R.J. Maguire (1957–69) and then Ken Henderson (1969–84).

A loose grouping of persons with interests in Australian literature (and environmental history), as well as others with a focus on Asian studies, have followed with interest these developments. Funds have now been raised through donation to enable the National Library of Australia to proceed with will project so that eventually, through TROVE, new generations might be able to access the material originally produced in print.

Hemisphere was unique compared to other Australian general interest periodicals of the mid-twentieth century; perhaps only Hemisphere combined ‘Australian’ and ‘Asian’ material in its remit. It explored the ‘deep cultures’ embedded in these two terms. It moved beyond the sole imperative of defining ‘Australia’ to having a vision of the region beyond. (It was also probably unique in that although it began publication by and for the then-small Commonwealth Office of Education in North Sydney, it was published from Canberra for most of its publication life). It was not ‘controversial’ in dealing with Australian foreign policy and political issues of the day, such as the Vietnam War, and from current perspectives it lacked an autonomous Indigenous Australian focus, although, via articles on Australian ‘prehistory’, it was a significant publication that conveyed to the general reader scientific work of the era that broadened awareness of Indigenous settlement in Australia to beyond 60,00 years.

I trust this advice will be of some interest and that this important project will provide new generations with past perspectives on Australia and the region generally.

Ian Campbell, Sydney, NSW

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

_2.260_Mrs_LOUNT_INTERCEDING_WITH_SIR_GEORGE_ARTHUR%20copy.jpg)