- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ubiquitous shit

- Article Subtitle: A faecal history of French literature

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Freud once argued that the pleasure of shit is the first thing we learn to renounce on the way to becoming civilised. For Freud, the true universalising substance was soap; for Annabel L. Kim it is shit; and French literature is ‘full of shit’, both literally and figuratively, from Rabelais’s ‘excremental masterpieces’ Pantagruel and Gargantua and the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom through the latent faecality of the nineteenth-century realists to the canonical writers of French modernity.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

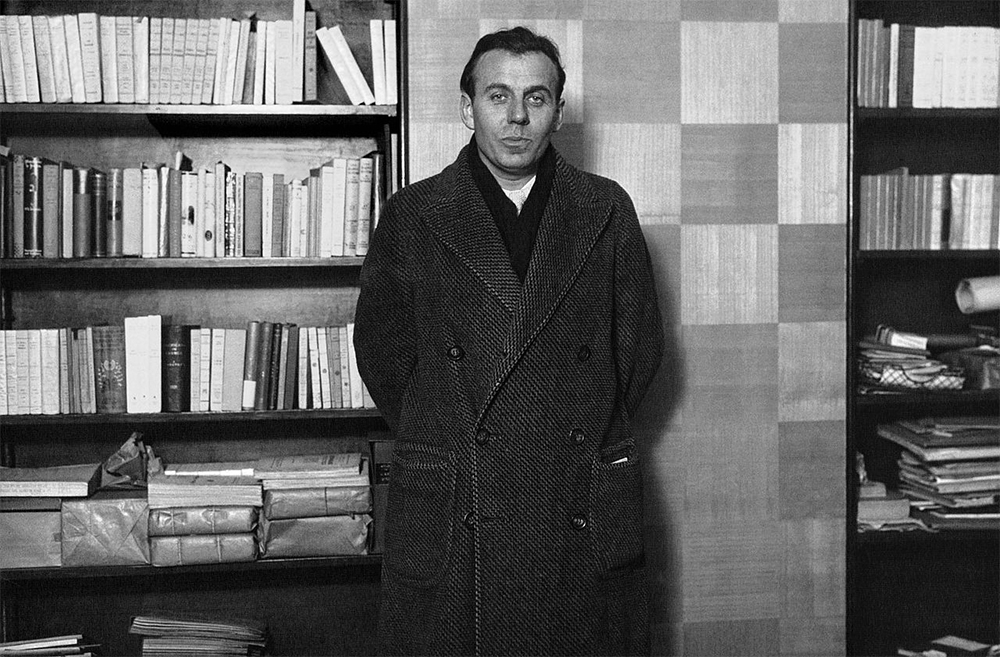

- Article Hero Image Caption: Louis-Ferdinand Céline, 1932 (Agence Meurisse/Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David Jack reviews 'Cacaphonies: The excremental canon of French literature' by Annabel L. Kim

- Book 1 Title: Cacaphonies

- Book 1 Subtitle: The excremental canon of French literature

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Minnesota Press, US$27 pb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/RydAYR

Cacaphonies offers an alternative history of French literature which calls into question the sanitising notion of a canon, restoring the faecal to its central place, not as a transgressive element to be pushed to one side but as the ‘fundamental component’ of modernity. This book seeks to demonstrate that twentieth-century French literature has ‘shed none of the fecality’ that typified its pre-industrial and early modern counterparts. Kim situates her book within the broader academic discipline of ‘waste studies’, a growing interdisciplinary field which ‘responds to the urgent ecological planetary crisis […] brought about by the production of more and more waste’. What Kim refers to as ‘literary waste studies’, while not directly concerned with the question of planetary survival, nonetheless deals with shit as a modern problem while insisting on ‘the connection between the medieval and the early modern and the modern and the contemporary’. The subject of fecality in literary waste studies has tended to focus on the medieval and early modern periods. What Cacaphonies attempts to do is shift this attention to the modernist French canon and to what Kim calls its ‘profound excrementality’. This excrementality cannot, Kim argues, be incidental to modern French writing; its omnipresence points to something more essential to the modern French literary enterprise.

Despite the unsavouriness of the subject matter, Kim’s argument is that whatever unpleasantness may arise is far outweighed by the ‘richness’ faecality offers as a way of understanding modern French literature. The first step in arriving at this understanding is an engagement with psychoanalysis and its monopoly on faecality in literature. What Kim calls ‘psychoanalytic fecal filtration […] flattens feces into a rather narrow identitarian frame, where thinking shit begins and ends with the self, the psyche’. Cacaphonies rather seeks to establish shit as ‘its own figuration … a conceptual and creative material that builds something other than the self’.

In late-nineteenth-century France, shit began to lose its corporeality – its existence as a ‘deeply embodied experience’ – and began instead to function more figuratively as ‘all the social entities that the bourgeoisie would like to purge from its social body’. Progress, the ideology of the Enlightenment, which saw the gradual sanitisation of France and its literature in the nineteenth century, went to shit in the early twentieth century. Literary modernism reflected this. Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s ‘excremental poetics’, particularly as it is articulated in his masterpiece Death on Credit, marked a return to Rabelaisian scatology and was the first attempt to both re-odorise the French literary imaginary and to reconnect the twentieth century with the early modern. Céline’s exploding of French literature cleared the way for Beckett, whose French-language trilogy Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable is for Kim the apotheosis of modern ‘excremental sensibility’, an outlook which encompasses at once past, present, and future. As Kim neatly summarises apropos of Beckett: we are of shit, we are in shit, and we are headed for shit. As a statement about the modern Zeitgeist, this is very persuasive, and these two chapters are the critical high point of the book.

Less persuasive is Kim’s attempt to forge a faecal connection between Jean Genet and Jean-Paul Sartre, two writers who, according to Kim, have more in common than at first appears, particularly when viewed through the lens of shit. While Genet’s transgressive politics and Sartre’s bourgeois public persona seem at odds with one another, their sensibilities ‘converge in faecality as a means of figuring and giving form to the idea of freedom’. The main obstacle to this convergence is that Sartre, even in his fiction, is not an overtly faecal writer. Kim attempts to overcome this by establishing an identity between the two writers based on Sartre’s Saint Genet: Genet as self-fashioned shit, Sartre as the ‘philosopher fly’ hovering over him. The result is the somewhat tenuous equation of faeces with freedom, both being essentially ‘anti-social, anti-relational [and] anti-hegemonic’.

The remaining two chapters take this idea as both their foundation and their point of departure, reorienting this concept of faecal freedom towards the figure of the other in the first step towards a faecal ethics. Through a reading of Marguerite Duras’s War and Romain Gary’s The Life before Us, Kim shows how these Holocaust narratives situate shit as ‘the exposition of a radical care ethics’. Duras ‘writes fecality in such a way as to point toward the universal instinctualizaton of care’ which transcends the typically gendered conception of care as feminine; while Gary’s chiastic ass wiping (the woman wipes the young boy, the grown man later wipes the old woman) establishes shit as the universal ethical substance, the true testing ground of our relationship with others. Finally, in the third part of the book, Cacaphonies leaves behind the French modernist canon and takes the leap into the twenty-first century. Here Kim looks at two contemporary novels, Anne Garréta’s In Concrete (2017) and Daniel Pennac’s Diary of a Body (2012), to demonstrate the ‘political uses of shit’ in our time; shit as an ‘anti-racist, anti-patriarchal material’ in Garréta’s case; and as ‘the democratization of literature and culture’ in the case of Pennac.

Cacaphonies has a clear teleology. While at times a little forced, it culminates in the utopian ideal of shit as the true universalising substance, the great leveller of difference and distinction. This ‘caca communism’, as Kim calls it, has both social and literary importance. However, Cacaphonies is primarily concerned with the way shit disrupts the French literary canon’s claim to the eternal because shit is precisely that ‘concrete, corporeal’ reminder of its impossibility.

Comments powered by CComment