- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘It’s me talking’

- Article Subtitle: Poetry’s vexed first person

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The lyric subject, literature’s most intimate ‘I’, has vexed critics for centuries. Is it the poet? Is it a fiction, a device? Or is the relation between author and speaker, as Jonathan Culler suggests, ‘indeterminate’, such that ‘any model … that attempts to fix or prescribe that relationship will be inadequate’? Two new award-winning Australian poetry collections offer fine-grained considerations of personhood and the poem’s capacity to represent it.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Anders Villani reviews 'Running time' by Emily Stewart and 'Inheritance' by Nellie Le Beau

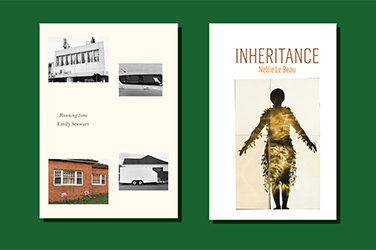

- Book 1 Title: Running time

- Book 1 Biblio: Vagabond, $25 pb, 75 pp

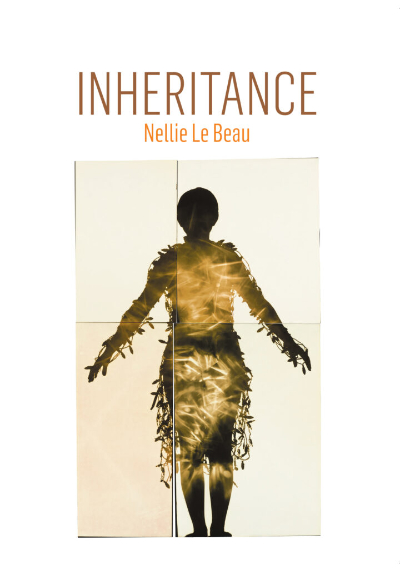

- Book 2 Title: Inheritance

- Book 2 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 74 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/May_2022/Inheritance-720x1024.jpg

Computational references populate the collection; driving this computing is what Stewart calls ‘the alluring challenge / of the unprocessed event’. In one poem, ‘phone turns Woolf to wooof’, an autocorrect to the incorrect that foreshadows the speaker’s later acknowledgment that ‘I know where I’m going wrong / flicking between screens / my mood is split / and my meaning.’ Existence threatens to reduce to ‘signing in from / whenever / always’. Elsewhere, Stewart puns on ‘browsing’:

stressed out glossy light

spiralling outside

feeling fine

getting back to

throwing a stone

browsing privately

The lineation here typifies Stewart’s poetics: short, fragmentary, parsed into discrete units, alive with sonic pattern. This formal approach, and the flat affect it fosters, compounds the sense of the poem as a cipher. What is ironic about such depersonalisation is how Stewart achieves it through a single first-person voice. In fact, the poet courts this irony: ‘this isn’t botspeak it’s me talking / um / about / our lighthearted r/ship’; ‘will you look it up / deepfaking literaturr’. At one point, we find the speaker ‘glowing up at my laptop / facing the wall / the vacant lot’. The human has become technology. Virtual space has become physical.

The quote above also reveals the book’s metapoetic dimension. Running Time tracks a writer using her medium to ‘inscribe [her] relations’ with the world. Sometimes, those relations suggest mystical agreement between language and thing: ‘in the instant of wakefulness / … / image and text lies evenly / forming the shape / of what happens next’; ‘the tide speaks pure verbiage’. More often, Stewart resists the tendency to mine imagery for symbolism. Part of the book’s code-like quality derives from its lack of specific, sensory images. When such images do appear, vivid because of their scarcity, Stewart bats them away as marks of the speaker–poet’s indiscipline: ‘Toyota Echo (intrusive image) / an old vernacular / where I spent too much time’. After an intimate disclosure – ‘I take my books to bed with me / I pause I catch a breath’ – the speaker in the next poem chides herself: ‘don’t backflip now / I’m aware I’m not everybody’s / sound.’

Readers of Running Time, which won the 2021 Helen Anne Bell Bequest Poetry Award, may find the first-person speaker unapproachable, given how little she reveals of her biography. Can the subject appear both omnipresent and evanescent, human and ‘bot’? Near the book’s end, a list arrives: ‘dislodged brick / wraparound sunglasses / a toddler’s sock / personal slight / Tasmanian Oak (5 planks) / rubber band / wrapper / stick’. Why this lurch towards things in a collection with so few? To declare that ‘this rummaging / is a live consciousness’. A consciousness ‘giving off / … a feeling not a lecture’. A consciousness that loves: ‘you / turn up against my thigh / crash the site’. Never encrypted from view for long is the lyric’s most human feature – its optative mood, or expression of wishes:

my fantasy is

that crisis is revelatory

that change is a process

I can trip the wire on.

‘I have spent / All morning,’ admits the speaker late in Nellie Le Beau’s Inheritance, ‘under wattlebird, / Asking the land.’ Asking the land what? A question for its own sake, but implying a responsive world, in which ‘tamarind sleeves’ are ‘rare / books pressed by sunlight,’ and ‘the night sky of Lynn’ is ‘bronze-aged, calling’. If Le Beau’s début spans myriad forms, geographies, points of view, and historical epochs, its keynote remains a subject’s immersion in – and attempt to sing – the numinous, ‘this gift / … / this infinite wing’.

Much of the collection, winner of Puncher & Wattmann’s 2020 Prize for a First Book of Poetry, is set in rural Australia and North America. Unfamiliar places accumulate and become their own music: Broken Bow, Delight, Telluride, Trois-Rivières, Prairie Siding, Paincourt. Such particularity extends to perception, often of flora and fauna: in ‘wattle season’, ‘Young emus / hang / foot-first caught / by the wire / loops of the white lamb / paddock’; ‘to the reed warbler’ celebrates the bird’s ‘chant, sharp / to the martens flitting seamless / above the water’s grain’. When a pod of beached whales lies ‘Heaving with the weight / Of oxygen, their lungs / Shutting out sunlight, closing / Like blinds at noon in the desert’, we think of the speaker’s father in another poem, moving from Niagara Falls ‘to a desert place, slicing / grapefruit with a new tongue’.

Yet, like Robert Haas and Gary Snyder, whom she quotes in epigraphs, Le Beau’s ecopoetic rootedness bursts into myth, allusion, and tangent. The book’s most impressive poems are its most formally and conceptually ambitious. In ‘Sepulchral’, the speaker is an entombed Denisovan human, ‘waiting for the new world’, and then a contemporary witness to a young woman entering or exiting a strip club, ‘tak[ing] the corner / like a tumbleweed’. ‘Long Haul’ apostrophises a flight attendant named ‘Agnieszka’, never to reappear, on subjects as diverse as ‘placing scrambled eggs in the microwave’ and ‘a ramhorn sliced in layers / of bone and meadow’. The speaker’s grandfather, a fur-trapper, and Scheherazade walk together between Ontario and Quebec, the queen holding his pelts. Gilgamesh enters a Richmond injecting room ‘search[ing] for the letters’ of an ancient stone tablet. ‘Canticle for Allen Dulles’, a former CIA director, ends with the speaker finding the man ‘in bear grass’: ‘I called to him, and moss became / his tongue and rivers settled / under black ice, dissolving / frost shards in every mouth.’ Le Beau closes multiple poems with such metaphorical flourish, calling to mind Haas’s ‘Interrupted Meditation’: ‘I’m a little ashamed that I want to end this poem / singing, but I want to end this poem singing.’

At the book’s heart is the power and resilience of the feminine – ‘the women’, the poet writes in ‘Praising the Northern Loon’, ‘who made me’. Le Beau thrice references the Hebrew Book of Esther, in which a woman saves her people from genocide. In one poem, the speaker, Esther herself, tells how ‘As a girl / Barefoot I collected / Owl feathers.’ Elsewhere, the speaker, now nearer the poet, who is nearer Esther, says: ‘As I girl I / favoured geese. Canadian, like / My father and the guns he kept / To scare them. I collected / Their feathers, named them.’ What happens to these collections, these names? They become poems, ‘Feathers … pasted / To light, measured / In stars.’

Comments powered by CComment