- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A living archive

- Article Subtitle: Mothering as the ultimate synthesis

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the beginning of 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write (2014), author, mother, and playwright Sarah Ruhl notes: ‘At the end of the day, writing has very little to do with writing, and much to do with life. And life, by definition, is not an intrusion.’ Ceridwen Dovey and Eliza Bell’s Mothertongues embraces, embodies even, this collapse of the boundaries between living and writing. Rather than extolling the proverbial ‘room of her own’, Bell and Dovey are asking us to heed the kinds of knowledge that come from being embedded in the everyday.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sarah Gory reviews 'Mothertongues' by Ceridwen Dovey and Eliza Bell

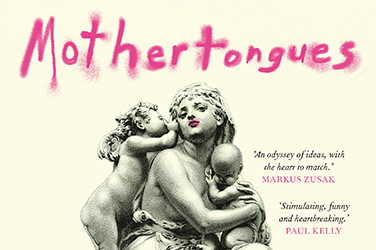

- Book 1 Title: Mothertongues

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $34.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/NKy5ob

Arranged in three acts, Mothertongues looks to theatre, particularly the tradition of the Theatre of the Absurd, as a framework to capture the ways motherhood upends our experience of time, and so of life itself. ‘As an artistic form,’ they write, ‘absurdism really captures something about motherhood.’ Mothertongues opens with a series of stage directions, a structural device that reappears throughout the book. A structural device, yes, but also a peek behind the curtain. A reminder that life writing is not necessarily confessional; that it is curated, which is not the same as being performative. Here, the theatrical works to refuse the artifice of ‘authenticity’ in favour of the anthropological. ‘This,’ Bell and Dovey tell us, ‘is the slice of life that we are preserving, performing.’

Mothertongues arrived in my letterbox the day before school holidays began, so I read most of it in parks and on beaches while my kids played, asked questions, requested food, insisted that I inspect a squashed caterpillar. This time, though, the fragmented style of reading engendered by their presence works in tandem with the text, complementing its structural fragmentation.

Taking as provocation Virginia Woolf’s clarion call to women writers to break convention, Mothertongues joins a rich thread of contemporary motherhood life writing that uses the fragment as a building block. One has only to look to Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015), Rivka Galchen’s Little Labours (2016) or Ruhl’s 100 Essays, among others, to understand how the fragment resonates with the confounding experience that is early motherhood. As a structure, it allows content and form to mirror one another, to inform one another. Motherhood is, after all, a masterclass in interruption, repetition, and moments of intense clarity.

Here, Dovey and Bell take the fragmented structure further, stretching it and playing with different devices from the theatrical, the conversational, the musical, the listicle; searingly honest one moment, farcical the next. Not every formal choice will work for every reader but taken as a whole they allow the text to lead us to unexpected junctures – just as the practice of motherhood can do. ‘Mothering is the ultimate synthesis of body and brain, spirit and intellect,’ Bell and Dovey write. ‘It’s like doing grounded philosophy every single day.’

There is a critique to be made that this book is yet another motherhood memoir written by white, middle-class, cis-het women (a demographic I fall into as well). While Mothertongues begins, seemingly, as a dialogue between Bell and Dovey, it becomes a polyphony of voices past and present, real and imagined: Samuel Beckett, Virginia Woolf, the authors’ own mothers, songwriter Keppie Coutts whose songs are integrated into the text, Siri and Alexa, and the list goes on. Within this polyphonic layering, I do wonder what kinds of spaces a broader selection of voices might have opened up. Despite Bell and Dovey’s formal ingenuity, the motherhood narrative contained therein is relatively traditional – the book begins, after all, with Bell meeting the man who will become the father of her children.

But while this critique is perhaps valid, it is also too easy. To leave it at that would be a disservice to the work the authors’ have done to make clear that this book is not supposed to be a universal rendering of the motherhood experience, but rather the beginnings of a conversation. And it is here, in the conversational, the polyphonic, that Mothertongues transcends itself. As I read, I lose track of which voice belongs to which author – indeed, it is rarely delineated anyway. After a while, I realise that it doesn’t matter, that the blending of voice creates a collective landscape of motherhood we are all invited into. The fragmented structure aids this sense of invitation, leaving space for our own remembrances, non sequiturs, meaning-making. ‘An actor is only really an actor when others are invested in the act of watching them,’ the authors write. At the heart of Mothertongues is this insistence on community as both political imperative and saving grace.

In the end, what Mothertongues offers is a text that opens possibilities not just for the ways we can write motherhood, but also for the ways we can think about it. Here, the mother–writer–self is fluid, amorphous – and not necessarily even singular. Mothertongues is a bold contribution to a genre of motherhood life writing that is refusing the boundaries of narrative convention, and of conventional wisdom about what writing the self should look like. In the final act, the authors profess the hope that more mother–writers will join them in the ‘strangely fertile’ space that this book has cracked open, so that ‘maybe over time our numbers will multiply’. Indeed, I think that they will.

Comments powered by CComment