- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cheese & Bacon Cheetos

- Article Subtitle: Ned Kelly as a Gen X teen girl

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

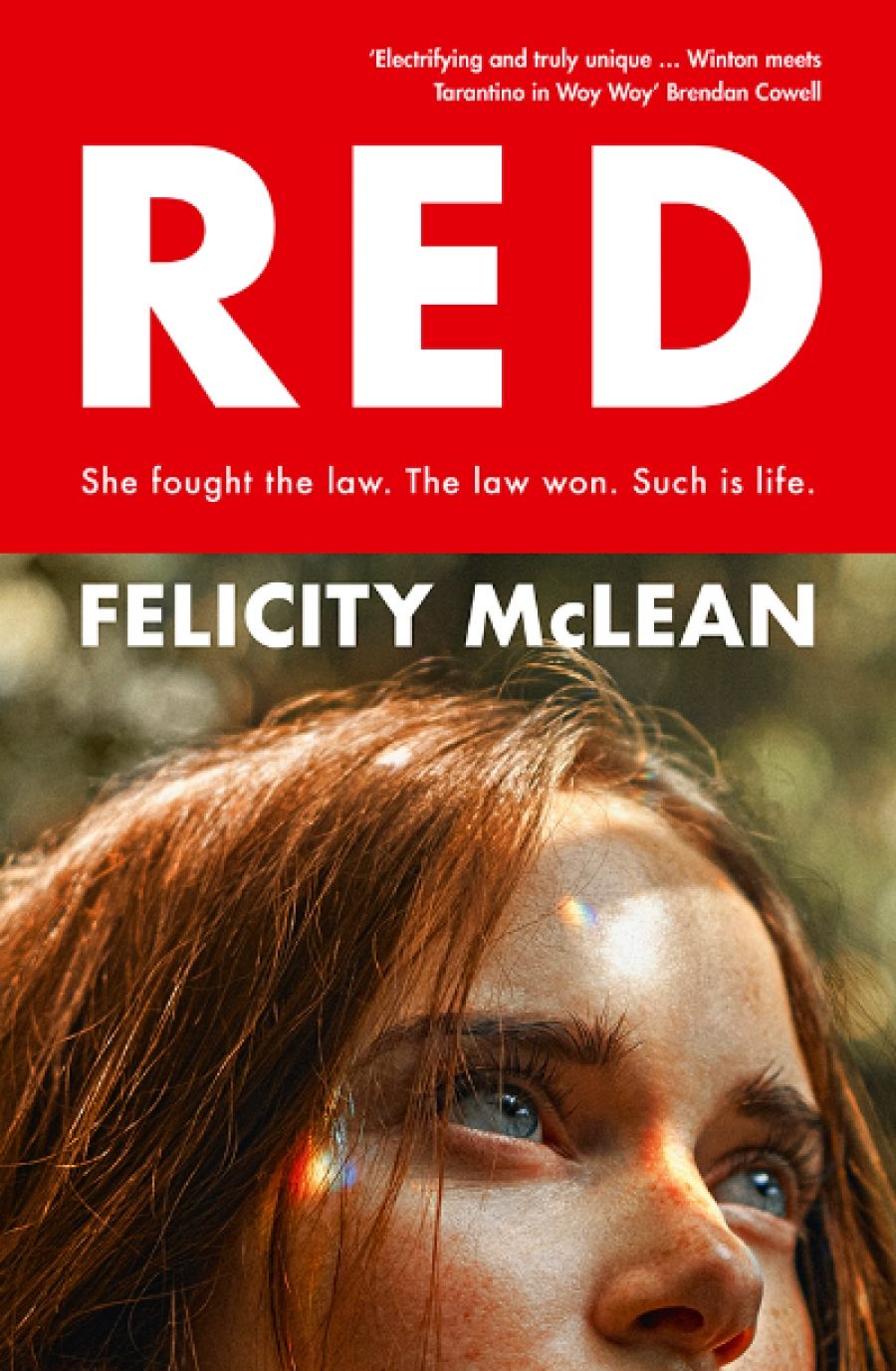

‘Everyone knows how it ends,’ declares Ruby ‘Red’ McCoy, the fourteen-year-old narrator of Felicity McLean’s second novel, Red. ‘What people are less interested in hearing is how it all got started.’ The ending in question is Ruby’s attempted murder of a police officer, a crime that is heralded from the novel’s outset. In this retelling of the Ned Kelly legend, McLean sets Red apart from existing depictions of the bushranger – from Sidney Nolan’s iconic series of paintings (1946–47) to Peter Carey’s novel True History of the Kelly Gang (2000) and its subsequent punk-infused 2019 film adaptation by Justin Kurzel.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Laura Elizabeth Woollett reviews 'Red' by Felicity McLean

- Book 1 Title: Red

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $32.99 pb, 256 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/YgmX4B

Taking inspiration from Kelly’s famous Jerilderie Letter, Red is both a confession and a manifesto, detailing the McCoy family’s longstanding feud with the local police, their misdeeds, and Ruby’s world view. Ruby’s voice is distinctive: often rambling, unpunctuated, and littered with redacted profanities. She has a fondness for similes, word play, and baroque descriptions (‘looking like a Grimm’s fairytale giant yeah like David’s f██ing Goliath’, ‘Easy come easy go easy as a ██ Sunday morning’). While there are moments of poetry and humour, Ruby’s language is frequently obfuscatory. One wonders at times if she is deliberately misleading the reader through her verbosity, or if she herself is unsure what she wants to say.

Ruby’s reliability as a narrator is further complicated by the cartoonishness of those around her. Sid, her ne’er-do-well father, communicates in ‘dad jokes’ and cockney rhyming slang. Her best friend Stevie is a compulsive liar. Sergeant Healy is a camp villain, all Brylcreemed blond hair and bombastic threats. Despite differences in age, class, and gender, characters often sound alike, appearing less like fully formed individuals than extensions of Ruby’s psyche. In itself, this isn’t necessarily a problem; Red is Ruby’s story, and it is entrenched in her point of view. However, while we learn how her story starts and ends, the question of ‘why?’ remains. Why, in 2022, retell the story of Ned Kelly as a Gen X teen girl?

Unlike the Kellys, the McCoys are not a large family, nor are they Irish convict–descendants rebelling against British rule at a time of anti-Irish sentiment. Ruby is the only child of a loving, if incompetent, single father. The much-vaunted feud between her family and Sergeant Healy’s only goes back as far as Ruby’s grandfather, Pep, and originates with a slight that strains plausibility. Acknowledging this, Ruby elaborates:

The Healys hated us for what Pep had done … but more than that they hated us for what we represented … To the Healys we were dole-bludgers we were housos we were blue-collar union scum we were durry-smokers flanno-wearers ... we were petrol-sniffers bong-users nang-abusers meth heads even worse than that we were poor …

She is quick to add that she and her father aren’t ‘half these things’. Sid drinks, but he’s not an alcoholic. The McCoys’ pantry is poorly stocked, but Ruby doesn’t seem to mind eating tomato sauce sandwiches let alone to be at risk of malnourishment. She attends school and is a precocious reader, referencing The Grapes of Wrath, True Grit, and The Children’s Bach. She adores her larrikin father and his hare-brained mates, who have names like ‘Chook’ and ‘Ferret’. If the McCoys are poor, theirs is a happy-go-lucky poverty, without shame or desperation. They wear their flannel shirts with the blitheness of celebrants at a bogan-themed fancy dress party.

McLean’s choice to spare her heroine from the darker realities of intergenerational poverty – addiction, abuse, illness, educational disadvantage, housing instability – robs the central conflict of both verisimilitude and moral complexity. The McCoys seem to be targets of police discrimination not because they are disadvantaged but because they are wily, spirited, and fun-loving, and because the corrupt cops need somebody to victimise. The ‘petrol-sniffers’ and ‘meth heads’ whom the McCoys supposedly represent are absent from the narrative. There are no sex workers or rough-sleepers. Racial profiling does not exist in Red, as racial diversity does not exist.

Which brings us back to the ‘why?’ Why update such a quintessentially Australian story of police violence and discrimination, without their contemporaneity? The 1987–91 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was underway during the period in which Red is set. Since that time, a further 500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have died in custody. Recently publicised text messages exposed Zachary Rolfe, the policeman acquitted of the murder of Warlpiri man Kumanjayi Walker in March 2022, describing his work in Alice Springs as ‘cowboy stuff with no rules’. After being turned away from visiting Sid in prison 173 pages into the novel, Ruby bemoans: ‘What is it with this country and separating kids from their parents we’ve got form here oh we’ve got history.’ This insight is the closest Red gets to acknowledging the existence of Aboriginal people and the ongoing issue of state-sanctioned genocide, yet it swiftly takes a back seat to Ruby’s musings on Cheese & Bacon Cheetos.

For all McLean’s enthusiasm for the Kelly legend, and her formal inventiveness in rehashing it, the author fails to engage meaningfully with colonial history and its reverberations. For all her name-checking of 1980s working-class Australian culture – from Neighbours to Kerri-Anne Kennerley to Cottee’s Cordial – McLean offers only a celebration of Australiana, detached from the inequities of life in Australia.

Comments powered by CComment