- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: Gwen Harwood and the perils of reticence: Notes of a son and literary executor

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Gwen Harwood and the perils of reticence

- Article Subtitle: Notes of a son and literary executor

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Ann-Marie Priest wrote to me in 2015 asking whether she might talk to me about her proposed biography of my mother, and requesting my permission to examine some correspondence in the Fryer Library, which I, as Gwen Harwood’s literary executor, had placed on restricted access, I replied with a terse refusal to cooperate. Since my mother’s death in December 1995, I had kept tight control of her vast correspondence, nearly all of which she had donated to various research libraries over the last two decades of her life, and I saw no reason to change my ways.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

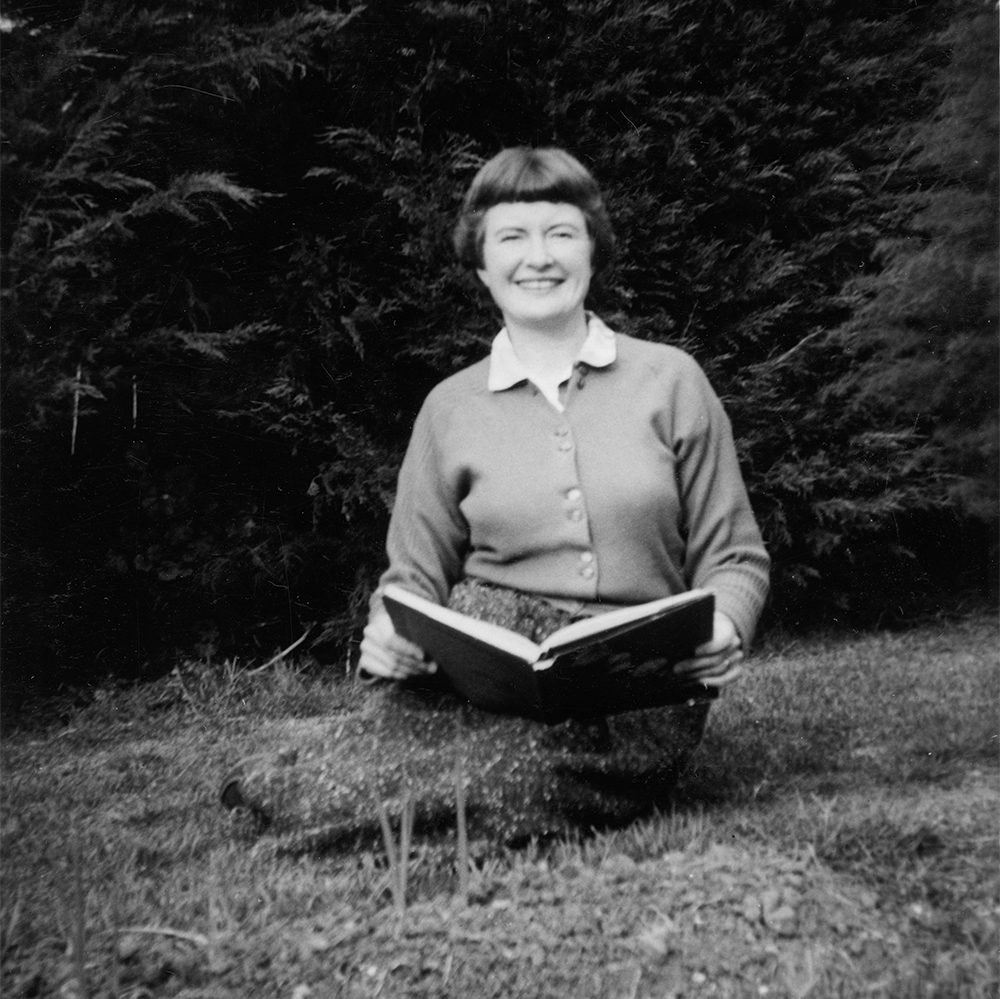

- Article Hero Image Caption: Detail from 'An outdoor portrait of Gwen Harwood in 1959'. Previous Control Number: UMA/I/7047 Previous Control Number: BWP/26275 206872 Item: [2005.0004.00008]. Photograph from Meanjin/C.B. Christesen collection, University of Melbourne Archives. Photographer unknown.

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Detail from 'An outdoor portrait of Gwen Harwood in 1959'. Previous Control Number: UMA/I/7047 Previous Control Number: BWP/26275 206872 Item: [2005.0004.00008]. Photograph from Meanjin/C.B. Christesen collection, University of Melbourne Archives. Photographer unknown.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): 'Gwen Harwood and the perils of reticence: Notes of a son and literary executor' by John Harwood

My father, F.W. (Bill) Harwood, a mathematical linguist who despised poetry in general and regarded my mother’s poems, in so far as they even touched upon his own life, as an unconscionable invasion of his privacy, was in his mid-seventies and in poor health, whereas my mother, despite ominous warning signs about her own health, fully expected to live to a hundred and to be present at the launch of her own Life. Instead, in January 1995, she was diagnosed with terminal cancer. During her last bleak year of ever-decreasing mobility and remorselessly encroaching pain, she invited me to act as her literary executor, and I accepted.

I was well aware, when I did so, that my parents’ marriage had been far from harmonious. They were, in temperament and belief, polar opposites: my mother impulsive, gregarious, extravagant in her loves and hates (but quick to forgive, no matter what the offence); my father reserved, solitary, averse to displays of emotion (though unfailingly loyal to, and greatly loved by, his own circle of friends). She was profoundly committed to the high Romantic vision of art and music and love as the ultimate sources of meaning in life, and to the rituals (though not the doctrines) of high Anglicanism. He was a diehard materialist, atheist, and behaviourist who had spent his working life seeking to develop a set of algorithms capable of programming an AI, as we would now put it, whose speech would be indistinguishable from our own, thus proving that human beings (with the possible exception of himself and his close associates in this endeavour) were no more than self-deluded automata. (He was also a highly skilled craftsman who would, I suspect, have been much happier running a boat yard.) My parents had been trying to convert each other for close on half a century, during which my mother, who had spent six months in an Anglican convent in her early twenties, had lost her faith in the biblical God, and read deeply into Ludwig Wittgenstein. My father had not moved an inch.

Likewise, he seemed perfectly content to live out his days in Hobart, where he had been appointed as a lecturer in English immediately after his discharge from the navy in 1945, whereas my mother, from the moment of her arrival in Hobart, saw it as a place of chill desolation:

Even as I say How Beautiful How Charming

why do I feel that some demonic presence

hovers where too much evil has been done …

(‘1945’)

From that day forward, Brisbane would forever be the ‘blessed city’ of warmth and light, lost freedom and lost loves. And she would rail against the constraints of marriage and childrearing, not only in private but in some of the most powerful poems ever written about the plight of the gifted artist driven to create and yet condemned to domestic slavery because she happens to have been born female. As her fame grew in the 1960s (along with her four children), she contemplated leaving my father. But in 1964 he was diagnosed with severe Type 1 diabetes, which then meant that he could easily die of hypoglycaemia if left unattended, and so she stayed, lamenting her exile from Brisbane more and more vehemently as the decades passed.

In their last years together, he offered (more than once in my presence) to divide their assets equally so that she could return to Brisbane, but she would not accept, for fear, I think, of being haunted by guilt if he were to die alone. As several of her poems testify, she knew on some deep level that the ‘Blessed City’ she longed to return to was the youthful self from whom she had parted in 1945, the life she might have lived:

Though you summon the dead

you cannot come as a child to your father’s house.

(‘Return of the Native’)

And yet, for all the savagery of poems like ‘Burning Sappho’, ‘Suburban Sonnet’, and ‘In the Park’, the husbands (there is almost always a dramatic element in her work, no matter how unmediated it may seem) are not presented as villains or monsters; there is, rather, a sense of inevitability: this is simply how things are, how gifted women are bound to end up if they choose to marry. Other equally personal poems insist, with equal force, that she has chosen freely:

No hand

ravished me from the height I claim.

Freedom is power to choose. Each day

I choose my life, choose to be woven

in other lives …

(‘Littoral)

And few readers, encountering ‘Iris’, when it first appeared in 1971, would have doubted that the marriage depicted – undeniably her own, right down to the specifications of the boat my father built – was rock solid:

Give me your hand. The same pure wind, the same

light-cradling sea shall comfort us, who have

built our ark faithfully. In fugitive

rainbows of spray she lifts, wave after wave,

her promise: those whom the waters bear shall live.

(‘Iris’ was, ironically, the poem that most infuriated my father: when he came upon it in The Australian he was speechless with rage that she should dare to write so openly of their marriage – and be read by so many.)

This, at any rate, is roughly how I would have sketched the marriage at the time of her death. For all her railing against being stuck in freezing Hobart with HIM – an icy monosyllable generally uttered through gritted teeth – she had after all stayed, and, indeed, had died holding his hand. But a few months later, Gregory Kratzmann told me that my mother had had several affairs during the marriage, not to mention a two-year affair with her married music teacher in Brisbane, beginning when she was seventeen, all of which she had freely, and by the sound of it eagerly, discussed with Kratzmann before her final illness. In one mood, he said, she would exhort him to ‘go for broke’ and Tell All; in another she would insist that ‘we mustn’t do anything that would hurt Bill’ – not, at least, until he was safely dead.

But now she was dead, and I, as her executor, had the power to determine what, if anything, I would allow Kratzmann to quote from her massive correspondence. (Whereas extracts from published works may be quoted without permission according to the terms of ‘fair dealing’, unpublished correspondence is fully protected, as Ian Hamilton discovered late in the writing of what became In Search of J. D. Salinger.) I loved my parents equally and was determined that, so far as I had anything to do with it, nothing that might distress my father or his many old friends would find its way into print.

Thus Kratzmann and I were set on a collision course. He had a contract for a biography; I was prepared to countenance Gwen Harwood: A literary life, as it were – leaving out the affairs and anything (much) about marital distress – whereas he believed that my mother’s ultimate wish was for him to Tell All. He could, of course, have proceeded by loosely paraphrasing from the embargoed letters, which he had already photocopied. But that might have led to difficulties with his publisher (Oxford University Press), and in any case he did not wish to alienate me and my siblings. He therefore agreed to edit a volume of correspondence on my terms, and so A Steady Storm of Correspondence, after rigorous pruning by me, appeared in November 2001.

Some readers were aware of what had been left out; others wondered why so many of the letters had been excerpted. But my father was still alive, and so were friends and family who would have been deeply distressed on his behalf. By a strange coincidence, he died of a heart attack a few days before A Steady Storm was launched in Hobart.

There was no other biographer then in prospect: Kratzmann and Hoddinott went on to edit a fine edition of Gwen Harwood’s Collected Poems 1943–1995 (2003), and I continued in my role as keeper of the flame, happily approving the reproduction and performance of her poems and libretti whilst keeping much of her archived correspondence (of which I had read only a fraction) under embargo. I more or less assumed that things would go on thus indefinitely, with A Steady Storm taking the place of the biography my mother had hoped for.

Then last year, I read Ann-Marie Priest’s ‘Baby and Demon: Woman and the Artist in the Poetry of Gwen Harwood’ (2014) – which I ought to have read when she first wrote to me – and realised belatedly that Gwen Harwood, despite my best efforts, had found her biographer. My Tongue Is My Own is exactly the Life that Gwen Harwood – that is to say Gwen Harwood the poet, musician, and unconquerable free spirit despite all the burdens of domesticity – would have wanted. With admirable enterprise, Priest has tracked down the thousands of letters I had embargoed, and trawled through public records in search of many small but illuminating details which would otherwise have been lost. And she has orchestrated Gwen Harwood’s protean voices with such inwardness and authorial restraint that her narrative often reads like autobiography at its most compelling.

Many people will, I imagine, be drawn to this book by their love of the poems, without perhaps knowing much about the poet beyond the anodyne biographical sketches available online. To them – and even to those familiar with A Steady Storm – My Tongue Is My Own may come as something of a shock – as it has to me, not necessarily because of the love affairs mentioned above, although readers can now put names to the lovers and beloveds central to many of the poems. But the fifty-year marriage at the heart of the story takes on a darker hue; darker than I had anticipated. (The irony of my being the one person who had free access to the archive all along isn’t lost on me.)

When Gwendoline Foster met Bill Harwood in September 1943, she was free to go where she liked, do what she liked, and love whom she liked, all with her devoted parents’ blessing. She and Bill fell deeply and passionately in love, but the warning signs were clear. Whereas she regarded love as an infinite resource, like sunlight, he wanted her exclusive devotion; he was jealous even of her piano-playing, despite the joy it brought her. ‘If he could make me invisible to everyone else,’ she wrote at the time, ‘he would do so gladly.’ He insisted that she break with all of her male friends, and burn every letter she had ever received from a man.

To all of these demands she willingly acceded: ‘If I am to be Bill’s I can keep nothing,’ she told her closest friend, and later: ‘What you see as tyranny is only the immeasurable demands of love.’ As Priest remarks: ‘Donne’s love poems and the language of Christian mysticism came together for Gwen in a kind of frenzy of self-surrender.’

Their first home was an isolated cottage halfway up Mount Wellington; Bill took over Gwen’s savings and kept all their money in his own name, doling out just enough for household expenses (she, of course, did all the housework). He chose their friends, discouraged all other visitors, and would not buy her a piano: ‘The loss was so intolerable, she would later say, that she turned to poetry to assuage it.’

Nevertheless, she thought of their marriage, during those early years, as happy. So long as she adapted herself precisely to his wishes, he was a loving and devoted companion. When crossed, he would retreat into cold silence, which she found unbearable; she would rather deform herself than endure his disapproval. To their mutual friends, they seemed an ideal couple: ‘they admired one another’s intellect and – crucially – laughed at one another’s jokes’. The young Alison Wright (later Hoddinott) was drawn ‘like a magnet to evenings of laughter, of discussion, of argument’.

As the 1950s passed, Gwen became more assertive in making friends of her own, despite the demands of four small children. Then in 1957 she fell ‘deeply, truly, tragically in love’ with a married man ‘who loved me & did not wish to change me’. The affair lasted only a few weeks before he was posted to Sydney; they both had young children whom they could not contemplate leaving, but the loss of him left her sleepless and distraught for many months.

My Tongue Is My Own is, first and foremost, a portrait of an artist compelled, in circumstances that would have defeated many people, to transform herself into a poet of extraordinary power and technical virtuosity. She acquired a piano, earned her own money, secured her reputation, travelled alone interstate, had love affairs. Much of the time, she and Bill got on perfectly well, but though the balance of power had shifted, the essential dynamic of the marriage remained: when crossed, he would retreat into ‘scaly coldness’, as at the publication of ‘Iris’ in 1971: ‘He hates my poetry almost as much as he hated my musical activities,’ she lamented. His diabetes inhibited her from leaving him; whenever she resolved to end the marriage regardless, his health took another turn for the worse, until it seemed, in the mid-1970s, that he had only a few years to live.

When Hoddinott began working on the letters that would make up Blessed City, Bill’s fury erupted again. ‘He really worked me over,’ Gwen wrote to Hoddinott in 1986, ‘his knowledge of what is in them is minimal but he is furious with me 1) for ever giving anything to the Fryer 2) for letting the material out of Dracula’s vault 3) for ever having written anything … I no longer have the strength to fight off his emotional blows. It’s absurd that we ever got married.’

Bill was never violent, and never used the threat of violence; Gwen would certainly have left him if he had. Cold withdrawal, and lectures on her ‘defects of character’, were his weapons of choice, and she could never distance herself sufficiently to blunt them. When Blessed City appeared in 1990, and a visitor asked Bill what he thought of it, he replied, ‘I read a couple of pages, but it was so UTTERLY BORING I gave up.’ As Gwen remarked to Alison: ‘The equivalent in a drunken wife beater would be a blow to the face I suppose.’

Though Priest’s account is scrupulously even-handed, and far more nuanced than this sketch might suggest (she encourages us to understand, rather than simply condemn, my father’s conduct), the point of view throughout is almost exclusively my mother’s, not only because it’s her Life but because my father, to the best of my knowledge, left nothing in writing that so much as hinted at marital discord. Whereas my mother, in her letters to intimate friends, was the equivalent of a singer who can not only span five octaves but also sustain a note at either extreme, pouring out her heart’s blood at sixty words a minute, wherever she could find space for her Remington. The raw intensity of her rage and anguish burns off the page, sweeping all before it.

Many readers will construe my father’s behaviour as coercive control (I already know of several who have). And up to a point it was. Coercive control, as we now understand it is, in essence, the isolation, financial control, gaslighting, and surveillance of the victim, enforced by violence or the threat of it; and deception of the victim’s friends and family (‘but he always seemed so devoted to her …’). My father did his best to keep my mother away from anybody he didn’t approve of, and to constrain her financially, but there was no violence and no deception. He was ruthlessly honest about his feelings: if he took a dislike to you, you would know all about it. Whereas if he did like you, he would be your friend for life (and gladly help you build your house, design and install you a watering system, or take you out sailing). The tributes at his funeral were heartfelt and unstinting.

The paradox at the heart of the marriage is that if my mother hadn’t married Bill Harwood (or had left him as soon as we children were grown), she might have lived a far happier life, but we wouldn’t have the poems. ‘If I’d stayed in Brisbane I’d never have written a line,’ she said to me on more than one occasion, meaning ‘if I hadn’t married Bill’. I’m sure she would have written many lines (assuming she hadn’t devoted her entire life to music), but not the ones that made her reputation.

This may sound perverse, given my father’s enduring hostility to her work. Part of his initial attraction for her was that he’d written his MA thesis on Coleridge’s theory of the imagination, but he was already reacting against literature; soon after they were married, he burned his thesis in the fireplace. His behaviourist, reductionist materialism, as I now see it, was a fortified enclave he had built to keep the troubling realms of art, literature, and music at bay. As my mother put it, around the time of his furious reaction to ‘Iris’: ‘Bill keeps telling me that poetry is just a language game but also that it is a violation of our privacy for me to write it – how can a “language game” be that?’ And later, speaking to a group of drama teachers: ‘Those who try to discount the imaginative use of language do so because they fear its power.’

My father, like many mid-century philosophers, misconstrued Wittgenstein as the ultimate positivist, whereas my mother understood that the concluding proposition of the Tractatus (‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent’) meant that everything that really mattered in life could not be analysed, only embodied in works of art. My father, sadly, learned nothing from their fifty-year debate, whereas she absorbed and transformed every argument he could muster. Throughout her work, scientific materialism is satirised to brilliant effect.

Likewise, the conflict between the demands of domesticity and the desire for absolute creative and emotional freedom is not only a defining theme, but a propelling force in some of her finest poems. (Priest is wonderfully insightful on this.) Throughout the marriage, friends would urge her to open her own bank account, offload the housework, insist on uninterrupted time for her writing, but she could never conquer her compulsion to be an ideal wife and mother. And if she had conquered it – as she asked herself on several occasions – would she have gone on writing at the same pitch of intensity?

My Tongue Is My Own leaves me with a heightened sense of the contrast between the angst-ridden letters raging against domestic slavery and marital torment, and the unfailing poise and self-awareness of her poetic voices. Grief at the loss of loved ones resonates throughout the poems, whereas the raw fury of those letters is transformed in them; the poems speak from above, from a plane of imaginative freedom where anger, resentment, guilt, and despair are transcended as each poem comes together at last. Both realms are equally real, but the transcendent self can only be inhabited fleetingly, in a realm beyond ordinary time, and once she finishes a poem she must descend into the everyday, where the clock is always ticking, never knowing for certain if she’ll be able to recapture that visionary delight. ‘I choose to be woven’ is itself written from the height of freedom.

Gwen Harwood’s sprezzatura – her seemingly effortless technique (rivalled, I’d say, only by Byron in Don Juan) – was essential to that transcendence. The power she commanded wasn’t, she always insisted, accessible just through writing things down, however heartfelt; she needed the constraints of form, something to push against, forcing her to rethink and rewrite (much of which she did in her head, in the midst of housework) and so work her way into what she really felt, thought, meant, believed. And when she pushed hard enough for long enough, she could enter another realm of being.

But mastery of form wasn’t enough; once she’d finished a poem, she never knew when (or if) her next real poem would come to her. Every poem was a gift, and the mystery at the heart of the process could never be explained, only embodied. From outside, of course, all of this can sound like mystical yearning. But for her, it was ultimate imaginative reality.

So, to conclude my executor’s tale: if I’d known what I was withholding, would I have done the same? Whilst my father was alive, yes; my mother knew, when she appointed me, that I would act as I did. Beyond that, I don’t know. But, thanks entirely to Ann-Marie Priest, it has all worked out for the best. My Tongue Is My Own deserves all the praise it is sure to attract.

This article was funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment