Yves Rees

The Transgender Issue by Shon Faye

Living through the world’s longest lockdown has few consolations, but abundant reading time is chief among them. I’ve read 136 books and counting in 2021, a tally that includes marvellous reads aplenty, with some definite standouts. Shon Faye’s The Transgender Issue (Penguin) is an astonishingly lucid argument for trans liberation that promises to become the canonical text on this subject. Faye’s thinking is on par with the best gender theorists of her generation, but her crystalline prose makes this book accessible for a mass audience. Equally memorable is Torrey Peters’s novel Detransition, Baby (Serpent’s Tail), a spiky comedy of manners that portrays millennial transfemme culture in 2010s New York. Closer to home, I adored Jennifer Down’s Bodies of Light (Text), an epic Bildungsroman that honours the dignity of crafting a life in the wake of childhood trauma, and I marvelled at S.J. Norman’s Permafrost (UQP), a beguiling collection of queer ghost stories.

Glyn Davis

The Labyrinth: An argument for justice by Amanda Lohrey

In the closed-in, introspective time of pandemic, the 2021 Miles Franklin judges wisely chose Amanda Lohrey’s The Labyrinth (Text) – moody and allegorical with overcast skies, distant waves, and silences. Though very different in style, Nicolas Rothwell’s Red Heaven (Text) has similar resonance, obscure events in an engrossing novel of ideas. Hermione Lee’s long-awaited Tom Stoppard: A life (Faber) proved an exemplar of modern biography. She gives us Stoppard as a central European intellectual recast by fate as an English schoolboy. Janet McCalman is a national treasure, and her Vandemonians: The repressed history of colonial Victoria (MUP) deploys her trademark approach: take the local and specific and use them to illuminate a whole stratum of life, in this case the secrets of former convicts who found their way to Victoria. Finally, 2021 saw the return of the pamphlet, through the innovative In the National Interest series curated by Louise Adler (Monash University Publishing). Here are multiple voices, in short but often powerful essays, grappling with substance.

Beejay Silcox

Grimmish by Michael Winkler

In January, I read two magnificent novels back to back: Grimmish (Westbourne Books) by ABR alum, Michael Winkler, and Painting Time (MacLehose Press) by French writer Maylis de Kerangal. It’s been a bountiful reading year, but I’m still raving about these early favourites. Painting Time is a tale of trompe-l’œil artists, painters of 3D trickery. De Kerangal revels in the sensuality of artistic mastery; hers is a novel of rich pigments and capable hands. Grimmish, meanwhile, is a feral, unpinnable creature. Ostensibly a biography of the thick-skulled boxer Joe Grim – a fighter most opponents could beat, but none could knock out – Grimmish takes the little that’s known of Grim’s life as an invitation to riff. Winkler’s ‘exploded non-fiction novel’ is a bruised and bruising vaudeville, complete with talking goat. It’s dissonant, doubt-ridden, grotesque, and entirely sublime. Twin novels of ecstasy: the pain of art, and the art of pain.

Peter Rose

The Promise by Damon Galgut

I’d not read the South African novelist Damon Galgut until The Promise (Chatto & Windus) came along. Then I had to read everything of his. Perspectivally, The Promise is full of Joycean slippages and subversions. Galgut – wry as Addison DeWitt – says of one of his characters: ‘She has a cat curled up on her lap. No, she hasn’t, there is no cat. But allow her a couple of plants at least.’ Well, allow us a few more novels by this brilliant satirist. And just when you thought nothing could be done to enliven or radicalise that old tart Biography, along comes Frances Wilson with Burning Man (Bloomsbury), her thrilling life of D.H. Lawrence, not long after her equally restorative study of De Quincey. Wilson’s prose reminds us of Hilary Mantel’s fiction: rhythmic, comic, surging with fact. Copious dangling modifiers aside, David Storey’s posthumous A Stinging Delight: A memoir (Faber) is the most fearless account of lifelong mental illness, familial woe, and sheer artistic grit. Finally, The Game: A portrait of Scott Morrison (Black Inc.), Sean Kelly’s illuminating psychological exposé of Scott Morrison, makes grim but essential reading. Seldom has Donald Horne’s diagnosis of Australia’s incurable good fortune seemed more apt.

Brenda Niall

Life As Art: The biographical writing of Hazel Rowley edited by Della Rowley and Lynn Buchanan

You don’t have to be a biographer to enjoy Life As Art: The biographical writing of Hazel Rowley, edited by Della Rowley and Lynn Buchanan (MUP). This vibrant collection of essays and journal extracts gives a portrait of the writer at work, engaging with her subjects, interviewing family and friends, negotiating with publishers. Above all, it shows the intelligence, curiosity, and empathy that Hazel Rowley brought to her biographies of Christina Stead, Richard Wright, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, and, just before her sudden death in 2011, a double portrait of the Roosevelts: Franklin and Eleanor. Jennifer Higgie’s The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, revolution and resilience: 500 years of women’s self-portraits (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) looks at women artists. How did they see themselves and why did they choose to put themselves on show, often in brutally candid versions? Hazel Rowley would have enjoyed exploring those questions.

Jennifer Harrison

Poems 1962–2012 by Louise Gluck

Since living in Boston from 1989 to 1991, I’ve followed the career of American poet Louise Glück. I was delighted when she received the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature. This year, a career-spanning publication, Poems 1962–2020 (Penguin Classics), brings together 697 pages of her extraordinarily precise and musical poetry. Among the many terrific books by Australian writers, I’ve particularly enjoyed John Hawke’s Whirlwind Duststorm (Grand Parade Poets) and Mal McKimmie’s At the Foot of the Mountain (Puncher & Wattmann). Both are innovative, intelligently creative, almost fearless collections. Finally, as a child psychiatrist I must mention Walk of the Whales (Hardie Grant Books), the new picture book by writer and illustrator Nick Bland. In his work there is a wonderful sense of poetic fun. The child in me trusts his vision completely.

Judith Brett

The Brilliant Boy: Doc Evatt and the great Australian dissent by Gideon Haigh

There was plenty of time to read during lockdown. Gideon Haigh’s The Brilliant Boy: Doc Evatt and the great Australian dissent (Scribner) concerns H.V. Evatt’s compassion as a High Court judge in a negligence case. A young immigrant boy was drowned in an unfenced council trench and his mother sued for her pain and suffering. Stuff happens, concluded the court’s majority; Evatt disagreed. One Hundred Days by Alice Pung (Black Inc.), told in the gutsy voice of a sixteen-year-old girl struggling for distance from her controlling, Chinese-Filipino mother, is a warm, funny, compelling read. Sean Kelly’s The Game: A portrait of Scott Morrison, the best thing I have read on our current prime minister, is full of insights and ideas. And to distract me from the troubles of the world, another Garry Disher, The Way It Is Now (Text), this time back on the Mornington Peninsula.

John Kinsella

The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley edited by Nora Crook and Neil Fraistat

I celebrate each time a new volume of the Johns Hopkins University Press The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley appears, and I do so again with the Nora Crook-edited seventh volume (JHUP). Out of sequence (the last volume published was the third) following the death of Neil Fraistat’s co-founding editor, Donald H. Reiman, this, to quote the editorial overview, ‘penultimate volume of this edition … consists almost entirely of the fragments and the few complete but unpolished poems that Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley included in the Posthumous Poems ... (1824)’. Rigorously, enthusiastically, and innovatively edited, this volume has brought excitement and zest to my Shelley-reading life. In a year of many significant volumes of new Australian poetry, I mention some standouts: Evelyn Araluen’s discourse-altering Dropbear (UQP), Maria Takolander’s confronting and sculpted Trigger Warning (UQP), Emily Sun’s cultural-presumption-shredding Vociferate | 詠 (Fremantle Press), and Toby Fitch’s existential linguistic meltdown Sydney Spleen (Giramondo).

Sheila Fitzpatrick

China Panic: Australia’s alternative to paranoia and pandering by David Brophy

First up, David Brophy’s China Panic: Australia’s alternative to paranoia and pandering (La Trobe University Press) provides some uncommon common sense on Australia’s current hyped-up alarm. If only one could hope that the panic-mongers would read it. In A Matter of Obscenity: The politics of censorship in modern England (Princeton), Christopher Hilliard takes us through England’s obscenity panics, from Lady Chatterley’s Lover to Oz, but in this case, as well as silliness and busybodying, serious questions were raised about the obligation of liberal societies to protect their members. In Destination Elsewhere: Displaced persons and their quest to leave postwar Europe (Cornell), Ruth Balint recovers a strange moment after World War II when Europe’s ‘displaced persons’ had to prove, by fair means or foul, their suitability for resettlement in Australia and elsewhere. Finally, for anyone wondering how ‘theory’ became an object of reverence in the humanities and social sciences in the late twentieth century, Philipp Felsch gives some funny and unexpected answers in The Summer of Theory: History of a rebellion, 1960–1990 (Polity).

Don Anderson

Leaping Into Waterfalls: The enigmatic Gillian Mears by Bernadette Brennan

It was, I think, French anti-novelist Michel Butor who suggested that we organise our personal libraries under friends. Here goes. Bernadette Brennan: Leaping Into Waterfalls: The enigmatic Gillian Mears (Allen & Unwin). The achievement of Brennan’s critical biography – scholarly, passionate, readable – is that it renders her subtitle otiose. But it is not her subtitle: it is the marketing department’s. For shame! Edmund Campion: Then and Now: Australian Catholic experiences (ATF Theology). Humane, literate, hospitable, engaging essays on, inter alia, B.A. Santamaria, Manning Clark, Lord Acton, John Henry Newman, and ‘Why I am Still a Catholic’. Even a non-Catholic may profit from it. David Williamson: Home Truths: A memoir (HarperCollins). A big book for a big life. Let us recall W.B. Yeats: ‘Think where man’s glory most begins and ends, and say my glory was I had such friends.’

Sarah Holland-Batt

Scary Monsters by Michelle De Kretser

Michelle de Kretser’s brilliant, chimeric novel Scary Monsters (Allen & Unwin) offers the reader two possible beginnings and endings, and two protagonists, Lili and Lyle, whose lives run on parallel tracks yet are rife with mirrorings, echoes, and inversions. While the novel’s dual settings are a dystopian near-future Melbourne and early 1980s France, its great trick is making the monsters of the present – racism, misogyny, ageism, Islamophobia, nationalism, ecocide – felt most palpably. Intensely poetic, bitingly satirical, poignant, and unsettling, Scary Monsters still hasn’t left me. I also loved Emily Bitto’s lushly baroque, ruinous, and fantastically inventive Wild Abandon (Allen & Unwin), which follows on from her Stella Prize-winning The Strays, and takes her Australian protagonist, Will, deep into the small-town wreckage of American capitalism. A devastating and sharply observed Bildungsroman concerned with masculinity and male friendship, Bitto’s unforgettable novel also has style in spades: its lyricism is exhilarating.

Anders Villani

The Shut Ins by Katherine Brabon

Katherine Brabon’s début, The Memory Artist, won the Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award in 2016, and her new novel, The Shut Ins (Allen & Unwin), cements her status as one of Australia’s finest and most innovative young novelists. Set in Japan and told in four voices, the book uses the story of Hikaru, one of the country’s young social recluses known as hikikomori, to reflect on more nebulous forms of personal withdrawal – from loved ones, from the self, and from the vital and unreachable ‘other side’ of life. What sets the book apart is Brabon’s decision to intersperse the main sections with ‘notes’ from a wandering, autofictional narrator, an Australian novelist in Japan for research. A conventionally plotted narrative thereby becomes a series of found testimonies, which both mask and accentuate the self-inquiry at the book’s heart. It is a poignant conceit, reminiscent of the work of W.G. Sebald and Patrick Modiano. I cannot think of another Australian novel like it.

Felicity Plunkett

When to Start and When to Stop: Advice for authors by Wisława Szymborska

For thirty years, Nobel Prize-winning Polish poet Wisława Szymborska wrote for the magazine Literary Life and responded anonymously to letters sent to its Literary Mailbox, offering ‘evaluation in one official-sounding sentence’. When to Start Writing (and When to Stop): Advice for authors (New Directions, translated by Clare Cavanagh) compiles this. Szymborska assessed its didactic value as ‘minimal, it’s mainly entertainment’. While the advice is often hilarious, this understates its sharp edges and compassion. ‘I sigh to be a poet,’ writes Miss A.P. ‘We groan to be editors,’ replies Szymborska, masked. Tracy K. Smith’s Such Color: New and selected poems (Graywolf Press) includes work from her four volumes with new poems. It maps sustained and exhilarating formal experimentation, song, and witness. Jhumpa Lahiri’s Whereabouts (Bloomsbury) tenderly parses a moment of uncertainty, exile, and hope in the life of its unnamed narrator obliquely, in poem-like, exquisite slivers.

Morag Fraser

The Magician by Colm Toibin

Two Irishmen and a South African-born Australian expanded my horizons during the months of confinement. All three wrote novels wrung out of that ur-generator of stories, the family, in all its permutations, fracturings, and cohesions. Colm Tóibín pondered Thomas Mann for years before committing himself to writing The Magician (Picador), his fictionalised rendering of the great German novelist’s life. Tóibín’s time was well spent – the novel is panoramic, and intriguingly intuitive about the repressions that fired Mann’s fiction. In Apeirogon (‘a shape with a countably infinite number of sides’), Colum McCann builds a complex form to tell of two men, one Palestinian, one Israeli, who each lose a daughter to conflict in the Middle East. Reading Apeirogon was like hearing small explosions of a poetry of revelation. In mid-winter, I reread all four Jack Irish novels, then The Broken Shore and Truth (all Text), and wished, fervently, that Peter Temple were still alive.

Gregory Day

Burning Man: The ascent of D.H. Lawrence by Frances Wilson

Much to my surprise, two of the books I enjoyed most this year were biographies, Frances Wilson’s incendiary retake on D.H. Lawrence, Burning Man, and Eleanor Clayton’s beautifully researched chronicle of Barbara Hepworth’s epic creative arc in Barbara Hepworth: Art and life (Thames & Hudson). Interestingly, these books take very different approaches to the biographer’s art, with the fearless Wilson attempting both a comic and a metaphysical take on Lawrence’s turbulent existence, while Clayton focuses on the elemental physicality of Hepworth’s work as the best possible description of her subject. The two approaches work equally well in the hands of such wonderful writers. I also loved two striking local poetry collections, Maria Takolander’s Trigger Warning and Save As by A. Frances Johnson (Puncher & Wattmann). Both of these collections contain some of the most moving confessional and elegiac poems you’ll read anywhere.

Nicholas Jose

Becoming a Bird: Untold stories about art by Stephanie Radok

A calendar year with its daily tour of the back yard and walks with the dog to the park as months go by. Artist–writer Stephanie Radok’s Becoming a Bird: Untold stories about art (Wakefield Press) is a marvellous book about the freedom of the mind to take wing from within the confines of a loved locality and a committed routine. Radok roams far and wide, remembering museum and art gallery visits around the world, books, places, and people, enquiring into complex things with a candid clarity of utterance and insight. ‘Who are you?’ a Prague cousin asks. The answer comes: ‘In this suburb in a room in a house in a garden in a book on a shelf behind a door in a cupboard, complete worlds are present and folded together.’ Not forgetting The Right to be Lazy by John Knight, a work of art the author saw in Berlin that consisted purely of weeds left to grow.

James Ley

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut

The two books that stood out for me this year were Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World (Pushkin Press) and Anwen Crawford’s No Document (Giramondo). The former consists of series of elegantly written biographical essays on some of the most brilliant mathematicians and physicists of the last century. Labatut weaves his accounts of their often remarkable lives into an exploration of the nature of genius and the psychological pressures that come with working at the limits of human understanding. Crawford’s book is a striking collage-like essay written in a spirit of lucid grief and righteous anger. Switching artfully between fragments of history, poetry, and memoir, its deliberately disjointed style belies the precision with which it has been assembled. No Document develops, slowly and purposefully, into a deeply considered and intensely personal reflection on the imperatives and disappointments of political resistance.

Jacqueline Kent

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

In such a gloomy, exasperating year, it was a relief to turn to a novel and a biography depicting such different – though perhaps equally difficult – worlds, especially with both books distinguished by such powerfully elegant prose and perceptiveness in evoking character. The Booker-shortlisted novel Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead (Doubleday), with its dual timeline and driven, courageous heroine, is not only a highly satisfying and enjoyable read but a meticulously researched account of 1930s aviation, its perils and challenges. It wears its learning lightly, as does The Brilliant Boy: Doc Evatt and the great Australian dissent by Gideon Haigh. Haigh’s clever use of one particular court case to illuminate the career of one of this country’s greatest lawyers produces an account that is exemplary in its forensic analysis and sympathetic treatment of a brilliant man whose contribution to Australian life has often been inadequately recognised.

David McCooey

Mike Nichols: A life by Mark Harris

In another bad year, it has been a good year for life writing. Mark Harris’s Mike Nichols: A life (Penguin Press) is a compelling and entertaining account of the film and theatre director’s remarkable rags-to-riches life. Lining up to register at the University of Chicago in 1949, Nichols struck up a conversation with the sixteen-year-old Susan Sontag. He had that kind of life. Compelling for different reasons is Polly Barton’s stunning Fifty Sounds (Fitzcarraldo), a memoir about living in Japan and learning the language, though, as Barton shows, ‘learning’ is too simple word for the enigmatic process of recalibrating one’s sense of both world and self. Lastly, I loved Things I Learned at Art School (Penguin) by the New Zealand writer Megan Dunn. This ‘memoir in essays’ is both hilarious and sad in extraordinarily inventive ways.

Tony Hughes-d’Aeth

Homecoming by Elfie Shiosaki

Elfie Shiosaki’s exquisite hybrid work Homecoming (Magabala) develops a new poetics of the archive. In a similar spirit to Charmaine Papertalk Green’s Nganajungu Yagu (Cordite), Homecoming is a matrilineal memoir that reclaims and re-creates culture, country, and memory. Also bristling with spiky maternal reclamations and intercultural electricity is Emily Sun’s volume Vociferate | 詠. It shifts suddenly from Keanu Reeves to Hong Kong television, and from Bak Kut Teh to Vagina Dentata. I was also really swept away by Caitlin Maling’s fourth volume of poems, Fish Work (UWAP). It follows the poet embedded on a research island in the Great Barrier Reef, where the fish are strange and the scientists even stranger. It has the terseness of an Anthropocene novella. In the background, the reef is quietly asphyxiating, while in the foreground the humans search for answers, and even for adequate questions.

A. Frances Johnson

The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, revolution and resilience: 500 years of women's self-portraits by Jennifer Higgie

Despairing at Covid’s artless halls, I turned to brilliant outliers of art-historical connoisseurship. Providing the most wonderfully immersive art experience outside of a museum, Jennifer Higgie’s The Mirror and the Palette is a spellbinding update of Germaine Greer’s and Linda Nochlin’s seminal feminist research. Julian Barnes’s updated Keeping An Eye Open (Jonathan Cape) includes seven revelatory new essays, ‘Berthe Morisot: No Profession’ and ‘Mary Cassat: Not Boxed In’ among them. Barnes’s signature dance between (unkosher) biography and a corrective desire to read works of art on their own terms is beguiling. Islands of Abandonment: Life in the posthuman landscape (Viking) by Cal Flyn extols the art of ecological resilience. This fine global study of abandoned towns and exclusion zones shows what happens when nature is allowed back in. The fine art of Australian poetry did not disappoint, new collections by Maria Takolander, Eileen Chong, Evelyn Araluen and others giving just the right jab.

Zora Simic

No Document by Anwen Crawford

My most eagerly anticipated read this year was Anwen Crawford’s No Document. At once a eulogy to a friend, a counter-history of the Howard years, and an art manifesto, No Document was so beguiling I read it twice. Veronica Gorrie’s Black and Blue: A memoir of racism and survival (Scribe) and The Mother Wound (Macmillan Australia) by Amani Haydar have lingered with me as powerful accounts of experiences that clearly needed to be told – in Gorrie’s case, of being an Aboriginal woman in the police force, and in Haydar’s, of the double loss of her mother at the violent hands of her father, and her grandmother to war. The most delightful surprise was Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle’s novella Nostalgia Has Ruined My Life, the best book this year about being a young woman who is extremely online. The book I never wanted to end was Bernadette Brennan’s enthralling biography of Gillian Mears, Leaping into Waterfalls.

Frank Bongiorno

The Game by Sean Kelly

I much enjoyed Sean Kelly’s The Game, which takes us underneath the forced bonhomie, artifice, and confections of our first post-truth prime minister to reveal a darkness about our politics and ourselves. It deserves to become a political classic. Gideon Haigh returns to a flawed giant of an earlier era in The Brilliant Boy: Doc Evatt and the great Australian dissent, a fascinating and moving story of callousness, compassion, and creativity centred on the unlikely topic of tort law. Melissa Harper and Richard White have assembled a rich feast in a new expanded edition of Symbols of Australia: Imagining a nation (NewSouth). Fresh essays on ‘The Great Barrier Reef’ by Iain McCalman and ‘The Democracy Sausage’ by Judith Brett remind us of how national imagining continues to evolve. Mark McKenna’s Return to Uluru: A killing, a hidden history, a story that goes to the heart of the nation (Black Inc.) is a powerful microhistory and meditation on frontier violence and its legacies.

Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen

Happy Endings by Bella Green

One of my favourite discoveries this year was audiobooks. Months alone in lockdown meant I took great pleasure in walking Melbourne’s inner north with a voice in my ears – a new way to experience storytelling. Memoirs by women were my favourite for this – I loved Bella Green’s Happy Endings (Macmillan Australia), Amani Haydar’s The Mother Wound, and Clem Bastow’s Late Bloomer (Hardie Grants Books), all narrated by the authors. These books cover such different topics – sex work, domestic violence, and autism, respectively – but all three are astute and illuminating. I read many novels this year for both work and pleasure, but none floored me as much as Jennifer Down’s Bodies of Light, equal parts devastating and hopeful. Down has long been a favourite writer of mine, and this saga – her most compelling and accomplished work yet – captures an entire life and all its nuances in arresting detail.

Brenda Walker

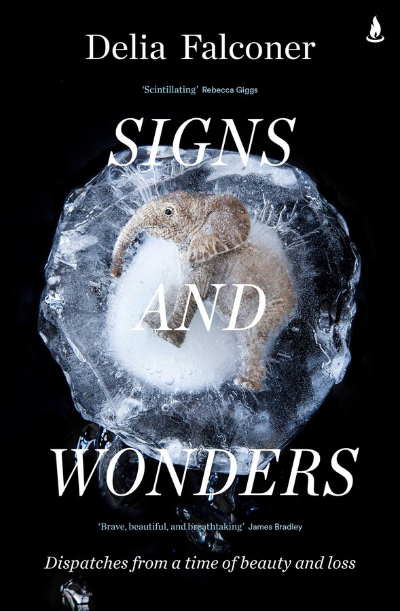

Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss by Delia Falconer

Delia Falconer’s Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss (Scribner) is an illuminating book on the climate crisis by a writer whose work, from The Service of Clouds on, reveals a powerful attachment to the natural world. The ‘signs’ of the title are quantifiable losses; ‘wonders’ include ancient creatures and artefacts exposed by climate change. Falconer brings them together, pointing out that ‘the web is constantly inviting us to marvel – and yet our wonder rarely translates into action’. Bernadette Brennan’s haunting biography of Gillian Mears, Leaping into Waterfalls, is an exceptional work. Helen Garner’s How to End a Story: Diaries 1995–1998, the third volume in this series, is equally notable. The entries have the taut shape of a fine novel, pivoting between the revelations of the writer, her therapist and her husband, all set in Elizabeth Bay, the same area Falconer describes decades later as the scene of fire-induced smoke hazard and solitary Covid walks.

Geordie Williamson

The Dancer: A biography for Philippa Cullen by Evelyn Juers

Evelyn Juers’ biography of Phillipa Cullen, The Dancer: A biography for Philippa Cullen (Giramondo), is both a labour of love and a richly researched cultural history. I had no interest in dance and no knowledge of Cullen before opening The Dancer; Juers’s work obliged me to open my mind. Mark McKenna’s Return to Uluru is a metaphysical true crime story awful in its unfolding – one that reveals the whole continent as a crime scene. Yet the sense of Uluru as a place of power and site of potential reconciliation is what stays with the reader. May it change hearts and minds. Jennifer Mills’s The Airways (Picador) was launched into the vacuum of Covid lockdown, which is desperately unfair, since her queer ghost story is subtle and fierce – the work of an author coming into full command of her gifts.

Mindy Gill

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura

Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies (Jonathan Cape) is my favourite kind of novel – about language and the schism between what we say and what we actually mean. I love Kitamura’s deceptive use of linguistic and narrative simplicity as she reveals the many ways people go about their lives without having any ‘idea of the world in which they [are] living’. I returned again and again to Sarah Holland-Batt’s luminous essays on Australian poetry in Fishing for Lightning: The spark of poetry (UQP). My favourite essay is on the exquisite poem ‘On Loss’ by Antigone Kefala, which traces the history of the fragment from Sappho to the Romantics to T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. The collection is essential reading for anyone interested in poetry – and indeed literature. I love Jeet Thayil’s Names of the Women (Jonathan Cape), a feminist corrective to the New Testament, and biblical in the most fundamental of ways: its language is pure poetry.

Tom Griffiths

The Winter Road: A story of legacy, land and a killing at Croppa Creek by Kate Holden

A book that has stayed with me all year is Kate Holden’s powerful environmental parable, The Winter Road: A story of legacy, land and a killing at Croppa Creek (Black Inc.). It is a brilliant, sensitive work of non-fiction that disturbed my dreams. Holden analyses a murder at a farm gate that was really an act of terrorism; she puts the whole psyche of modern Australian settlement on trial. Delia Falconer’s Signs and Wonders captures the fragility and incredulity of living at a tipping point of earthly life where we experience the uncanny every day. Two superb books that challenge Australians with the responsibility of truth-telling are Henry Reynolds’s Truth-telling: History, sovereignty and the Uluru Statement (NewSouth) and Mark McKenna’s Return to Uluru.

Paul Giles

The Right to Sex: Feminism in the twenty-first century by Amia Srinivasan

The most surprising book I read this year was The Right to Sex (Bloomsbury) by Amia Srinivasan, born in Bahrain and now a professor at Oxford, a collection of essays that takes the stale bureaucratic and legal controversies around sexual harassment to a different conceptual level. I also enjoyed two expertly written novels of ideas by distinguished old hands. Richard Powers’ Bewilderment (William Heinemann), which articulates alternative universes through the mind of an autistic child, continues Powers’ unparalleled artistic project to assimilate complex scientific information within engaging narrative frameworks. Similarly, Michelle de Kretser’s Scary Monsters, besides being typographically ingenious in the way the book is produced, creatively repositions contemporary concerns around race, immigration, and national identity within a more expansive spatial and temporal orbit. De Kretser’s provocative and illuminating style, with its satirical edge, evokes conjunctions between different continents as well as across past, present, and future.

Alice Nelson

Mangiri Yarda (Healthy Country): Barngarla wellbeing and nature by Ghil’ad Zuckermann

Mangiri Yarda (Healthy Country): Barngarla wellbeing and nature (Revivalistics Press) by Ghil’ad Zuckermann (who holds the wonderful title of Professor of Linguistics and Chair of Endangered Languages at the University of Adelaide) and Barngarla woman Emmalene Richards – part of an ongoing project to reclaim lost languages – is an inspirational examination of the deontological and utilitarian benefits of language revival and the profound importance of reawakening languages that Zuckermann, who founded the trans-disciplinary field of revivalistics, calls ‘sleeping beauties’. Carole Angier’s 600-page opus Speak, Silence: In search of W.G. Sebald (Bloomsbury) is a fascinating and meticulous study of the elusive German writer. It raises fraught questions about the aestheticisation of catastrophe and the fine line between empathetic identification and appropriation. Second Place (Faber) by Rachel Cusk and Real Estate (Hamish Hamilton) by Deborah Levy both interrogate the woman writer’s quest for creative freedom and the complex geometries of human relationships.

Peter Goldsworthy

Harbour: Poems 2000–2019 by Kate Llewellyn

Kate Llewellyn is a living national treasure and, at eighty-five, still one of the most provocative performance poets in the country: acerbic, funny, heart-wrenchingly honest – and always in your face. Her poetry is at one end of a continuum with her frank memoirs, and her wonderful letters – everything feels fresh and spontaneous, even when hard earned. Harbour (Wakefield Press) is a more meditative book overall, a safer haven, but she is still plenty naughty. Jelena Dinic’s In the Room with the She Wolf (Wakefield Press) was the first collection of poetry to win the Adelaide Festival’s Unpublished Manuscript Award. Dinic arrived from war-torn Serbia in Australia at the age of seventeen, perhaps having packed the minimalism of her great compatriot Vasko Popa in her luggage. Her book is an understated wonder, a journey from war to peace, and from one poetic tradition to another. If there is a poem anywhere about language migration as subtle and moving and funny as ‘J like Y’, I have yet to read it.

Declan Fry

Byobu by Ida Vitale

Readers, look no further: Ida Vitale’s Byobu (Charco) is the best book of 2021. Cheers also to Sean Manning for bringing it into English. Andrea Bajani, grazie mille. If You Kept a Record of Sins (Archipelago) is a marvel – Frank Ocean set to paper, tender, diaphanous, and far more lovely than it has any right to be. Elizabeth Harris deserves kudos for her translation. Evelyn Araluen, how do you do it? Dropbear (UQP) showed us where it’s at! Emma Do, Kim Lam, oh my gosh – Working From Home (may ở nhà) – this book! Eunice Andrada, thank you for your care and TAKE CARE (Giramondo). Anwen Crawford, No Document. Bella Li’s Theory of Colours (Vagabond, 11/21), unholy progeny of Poe and Anna Kavan – thank you for this gloriously disquieting combo of image and text. Chelsea Watego said fuck hope and you should read Another Day in the Colony (UQP). Lucy Van, The Open (Cordite): read it with an increasing sense of excitement – that door!

Jane Sullivan

The Five Wounds by Kristin Valdez Quade

My happy surprise was a funny and heartbreaking début novel from Kirstin Valdez Quade, The Five Wounds (Allen & Unwin), about a year in the tough life of the Padilla family in a small New Mexico town. It begins with Amadeo about to play Jesus on the cross, and it never lets up. For me, Klara and the Sun (Faber) was the cleverest and most moving Kazuo Ishiguro novel since Never Let Me Go. Here’s humanity seen through the puzzled eyes of an artificial intelligence that gets so much wrong, yet has a heart in the right place. Anita Heiss’s Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray (Simon & Schuster) is a much-needed look at white settlement from an Indigenous maid’s point of view, and the delicately balanced yet inevitably unequal friendship she forms with her mistress.

Melinda Harvey

Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux

If I had to sum up in one word why I love Annie Ernaux’s books, I would say it is for their modesty. This is literature with absolutely no tickets on itself. As Ernaux says in A Woman’s Story, ‘I would like to remain a cut below literature.’ It seems to me no accident that Ernaux was born into a working-class family in Normandy. Ernaux writes to chronicle what has bechanced her – from a conversation overhead on a train to her own illegal abortion forty years ago – all the while subjecting this need to chronicle to ruthless questioning. These books completely trash the idea that writing memoir needs be a self-aggrandising enterprise. Two of her titles were reissued in English by Fitzcarraldo this year: A Simple Passion (48 pages) and Exteriors (74 pages). The occasion for the first book is a love affair with a man from Eastern Europe, but it is really a meditation on waiting. The second book collects sights seen in her neighbourhood of Cergy-Pontoise. These events often hinge on something human surviving the largely transactional encounters of urban life.

Andrew West

With the Falling of the Dusk: A chronicle of the world in crisis by Stan Grant

With more than three decades of journalism behind him – half of it in conflict zones and Asia – Stan Grant could have easily written a satisfying memoir of a foreign correspondent. But in With the Falling of the Dusk (HarperCollins), he has gone much further, producing an insightful analysis of a world unravelling since the 1990s. Always conscious of being an Indigenous man, he uses this identity, not as a fortress but as an opening to the world. Andrew Lownie’s The Traitor King: The duke and duchess of Windsor in exile (Bonnier) reveals what might have been had Edward VIII, sympathetic to Hitler, not abdicated the throne to marry Wallis Simpson. George Blake signed up to the communist cause during the Korean War. What Simon Kuper’s The Happy Traitor: spies, lies and exile in Russia: The extraordinary story of George Blake (Profile) illustrates so well is the way this little-remembered but hugely damaging Soviet agent quickly lost faith in communism once he escaped to its bosom in the mid-1960s.

Tony Birch

Love Objects by Emily Macguire

Emily Maguire’s Love Objects (Allen & Unwin) was my book of the year: a tender and aching story of love, dysfunction, and insight into those around us we may not understand but who do us no harm. Colson Whitehead’s Harlem Shuffle (Fleet) is both a page-turning crime novel and social insight into 1960s Harlem seen through the eyes and experiences of our sharp protagonist, Ray Carney, who takes us on a wild ride. Evelyn Araluen produced a remarkable poetry collection. Araluen interrogates colonial violence, the Australian literary canon, absent of the reality of an Indigenous presence, while reserving tenderness for the family, community, and Country that have shaped her creativity and politics. In Uprising: Walking the Southern Alps of New Zealand (Text), Nic Low invites us to experience a Maōri understanding of language, land, and history. The book provides both a comfort read and education.

Peter Craven

The Hands of Pianists by Stephen Downes

Stephen Downes’s The Hands of Pianists (Fomite) is an extraordinary book which appropriates the style and strategies of W.B. Sebald but then succeeds in equalling him in this dark enthralling drama of potential annihilation. Helen Garner’s How To End A Story is the most formidable book of excerpts from the diaries so far, a devastating portrait of the breakdown of a marriage and not least of the narrator: a staggering achievement. In less self-critical mode, David Williamson’s Home Truths is a continuously diverting account of a brilliant career. Hermione Lee’s Tom Stoppard captures the mesmeric charm of his subject as well as his depth. John le Carré’s Silverview (Viking) is a ghostly reminder of the creator of Smiley. Robert Bolano’s Cowboy Graves: Three novellas (Picador) has the breathtaking unpredictability of a literary master who rewrote the rule book, captivatingly. Karl Ove Knausgaard’s The Morning Star (Harvill Secker) is a novel in the vicinity of apocalypse told by a chorus of narrators through a spellbinding lens of realism.

Diane Stubbings

The Death of Francis Bacon by Max Porter

The Death of Francis Bacon by Max Porter

Max Porter produced two striking pieces of writing: All of This Unreal Time (Manchester International Festival), his monologue for actor Cillian Murphy, a luminous invocation celebrating the agonies and wonders of life; and The Death of Francis Bacon (Faber & Faber), a prose poem in which Porter engages in a private communion with Bacon, evoking both the rough and jagged energy of the art and the fractured confusion of a life enduring its last hours. Francis Spufford’s Light Perpetual (Faber & Faber) – a graceful and generous novel – reincarnates five children killed during war, vividly imagining for them long lives full of heartache and joy. Get past the mundane title and Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19 (Jonathan Cape) reveals itself as an experiment in narrative form that is both daring and thrilling. Bennett braids together writing, reading, and living, eloquently demonstrating that books carry us ‘back to the beginning’ of ourselves.

Obligations of Voice by Anne Elvey

Obligations of Voice by Anne Elvey