- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Return to the Old Mill

- Article Subtitle: The education of Wulff Scherchen

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 2002 the English filmmaker John Bridcut visited The Red House in Aldeburgh, the archive housing the papers of Benjamin Britten and his long-time partner, Peter Pears. Bridcut was early in his research for a project he would realise two years later as the documentary film Britten’s Children, and then, after another two years, as a book of the same name. I was then head of music at the Aldeburgh Festival, with a few books of my own on Britten under my belt. Partly because the topic interested me and partly because I was soon to leave Aldeburgh, I sidestepped the archive’s historical rectitude regarding Britten’s sexuality and told John that he really needed to track down and interview Wulff Scherchen, Britten’s lover in 1938, who had moved to Australia and was now known as John Woolford. I dug up the last address we had on file for him and left Bridcut to it.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Kildea reviews 'Wulff: Britten’s young Apollo' by Tony Scotland

- Book 1 Title: Wulff

- Book 1 Subtitle: Britten’s young Apollo

- Book 1 Biblio: Shelf Lives, £24 hb, 176 pp

It’s not that Scherchen had hitherto flown under the radar. Ten years before I met John, Scherchen had been gifted a walk-on part in the first volumes of Britten’s letters and diaries. There was something slightly unfocused about this appearance, however: over time the happily married and fecund Woolford had become squeamish about his famous ex-lover – as had the volumes’ principal editor, Donald Mitchell, as it turns out (significantly) – so the many letters between the two were quietly pocked with ellipses until they resembled nothing more than gushing adolescent enthusiasm for poetry and music (Wulff was the son of the distinguished conductor Hermann Scherchen), shared equally between two young men.

Bridcut considerably sharpened this focus – though with that touch of omertà that forever informs Englishmen in recollections of their own or others’ public-school adventures. He made a beautifully subtle film, gingerly stepping around the svelte elephant in the room. He convinced Woolford/Scherchen to return to the Old Mill in Snape, Suffolk, where his relationship with Britten had burned so brightly for those few months in late 1938. Here he gave a most touching interview to camera, at one point sitting on the mill floor, remembering the time he had sat there listening to Britten at the piano. (Britten was following W.H. Auden’s detailed playbook on the art of seduction.)

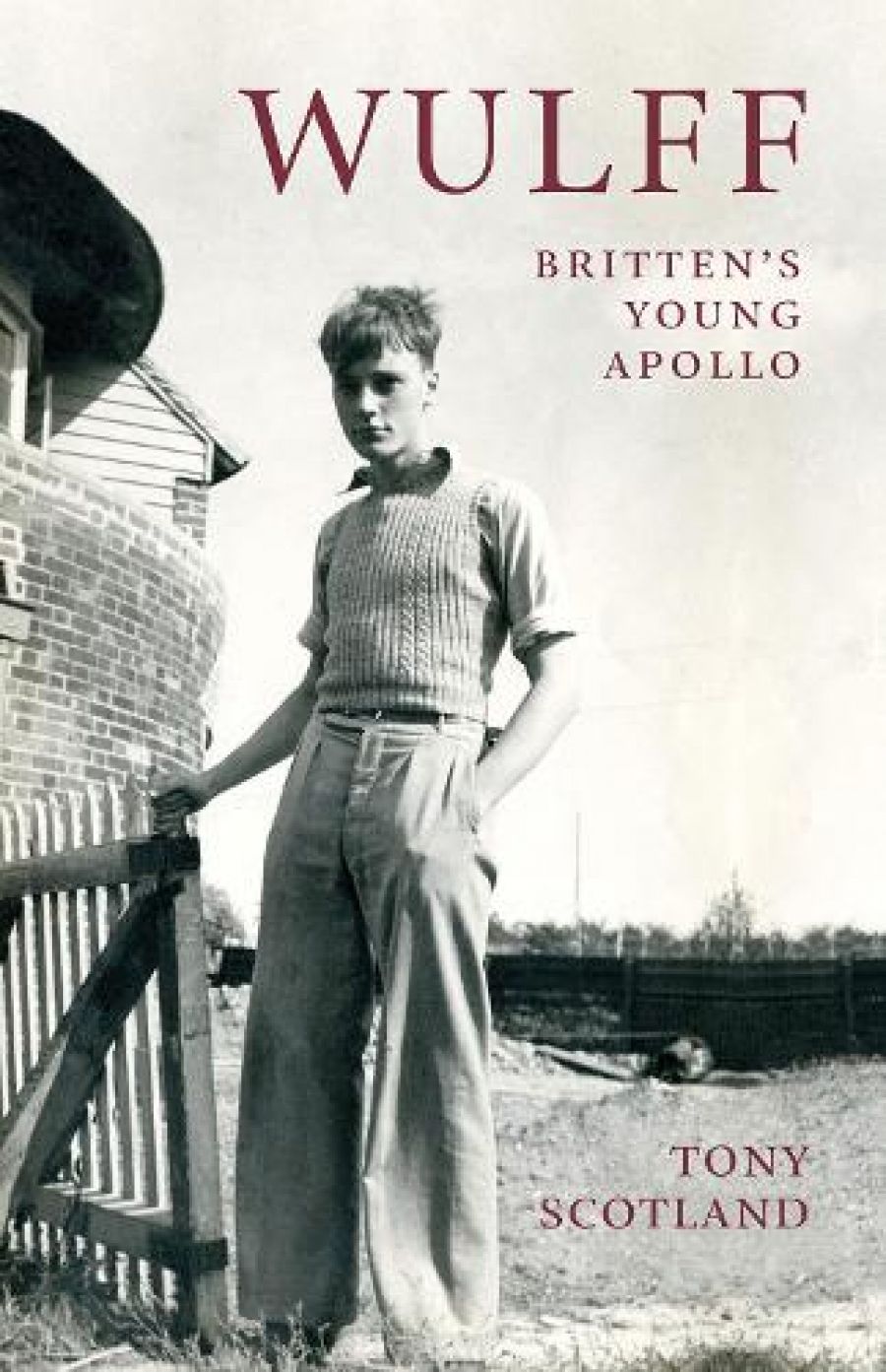

Two young men … The photograph on the front of Tony Scotland’s lovely new tribute to Scherchen doesn’t look terribly manly. Scherchen, in Oxford bags (though by then living with his mother in Cambridge), stands by the Old Mill’s front gate, looking to the world like a student on an exeat weekend. Britten didn’t look much less boyish in these years, though he was by then twenty-five (Wulff was eighteen). The Wolfenden report into the decriminalisation of gay sexual practices was still nineteen years away; neither the slight disparity in their ages nor Wulff’s youth made any difference here: the physical manifestation of their relationship was illegal regardless.

Scotland has done something rather sweet in this book: he has treated the relationship seriously, something Britten stopped doing with indecent haste once he had abandoned Wulff and England in early 1939, and something Wulff himself let slip away as marriage, parenthood, and embarrassment slowly captured him. Scotland has a personal connection with the story: his own partner is the son of composer Lennox Berkeley, whose infatuation with Britten in these years – and indeed his spell living in the Old Mill as Britten’s tenant and admirer – introduced a strong rip to the waters Britten was then attempting to navigate.

Scherchen’s slow-burn embarrassment meant that he cleaned up or papered over a key part of the relationship. ‘But wasn’t I lucky not to become involved in the sexual aspect of it all!’ he writes to Scotland not long after the latter’s excellent biography of Lennox and Freda Berkeley appeared in 2010. Acknowledgment of what he was involved in (or susceptible to) came only with his wartime internment in Canada with frisky or outspoken young enemy aliens his own age, if Wulff is to be believed (which he certainly shouldn’t be), and then later still through his marriage to Pauline, whose surname he adopted.

Scotland is also careful not to make his subtitle do too much heavy lifting. Scherchen was indeed ‘Britten’s Young Apollo’ – named after the radiant youth illuminating Keats’s ‘Hyperion’ – who inspired in Britten a somewhat thin piece for piano and strings, begun when ardour was at its height, though completed when both love and inspiration were waning. Scotland doesn’t attempt to argue that Scherchen was a long-time muse – Dora Maar to Britten’s Picasso, say – inspiring a stream of brilliant works that command ongoing attention and respect. Rather, he identifies Scherchen as an important part of Britten’s emotional development in these two or three pivotal years – years in the evolution of the composer’s outlook and output that saw a sequence of unparalleled scores: the Violin Concerto (1939), Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo (1940), and, finally, the triumphant Peter Grimes (1945).

Like others from this press, this is an uncommonly handsome publication, with writing to match. Vitally, it underlines the care, control, and (self-) deception required to maintain a gay relationship at the end of the 1930s, before war and mobilisation proved that birds, bees, and even young GIs do it. So much that followed in the 1950s and beyond in the adjoining fields of law and sexuality grew from this simple realisation.

Comments powered by CComment