- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A harbinger of new ways

- Article Subtitle: Janet McCalman brings the colonial paper trail to life

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Though a generation has grown up with online technology, we are only just starting to grasp what it means for our understanding of humanity. As a historian, I’m surprised to find that I can now trace the emotional and intellectual experience of individuals, through long periods of their lives, with a new kind of completeness. Fragments of detail from all over the place, gathered with ease, can be used to build up inter-connected portraits of real depth. A new inwardness, a richer kind of subjectivity, takes shape as a result.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Alan Atkinson reviews 'Vandemonians: The repressed history of colonial Victoria' by Janet McCalman

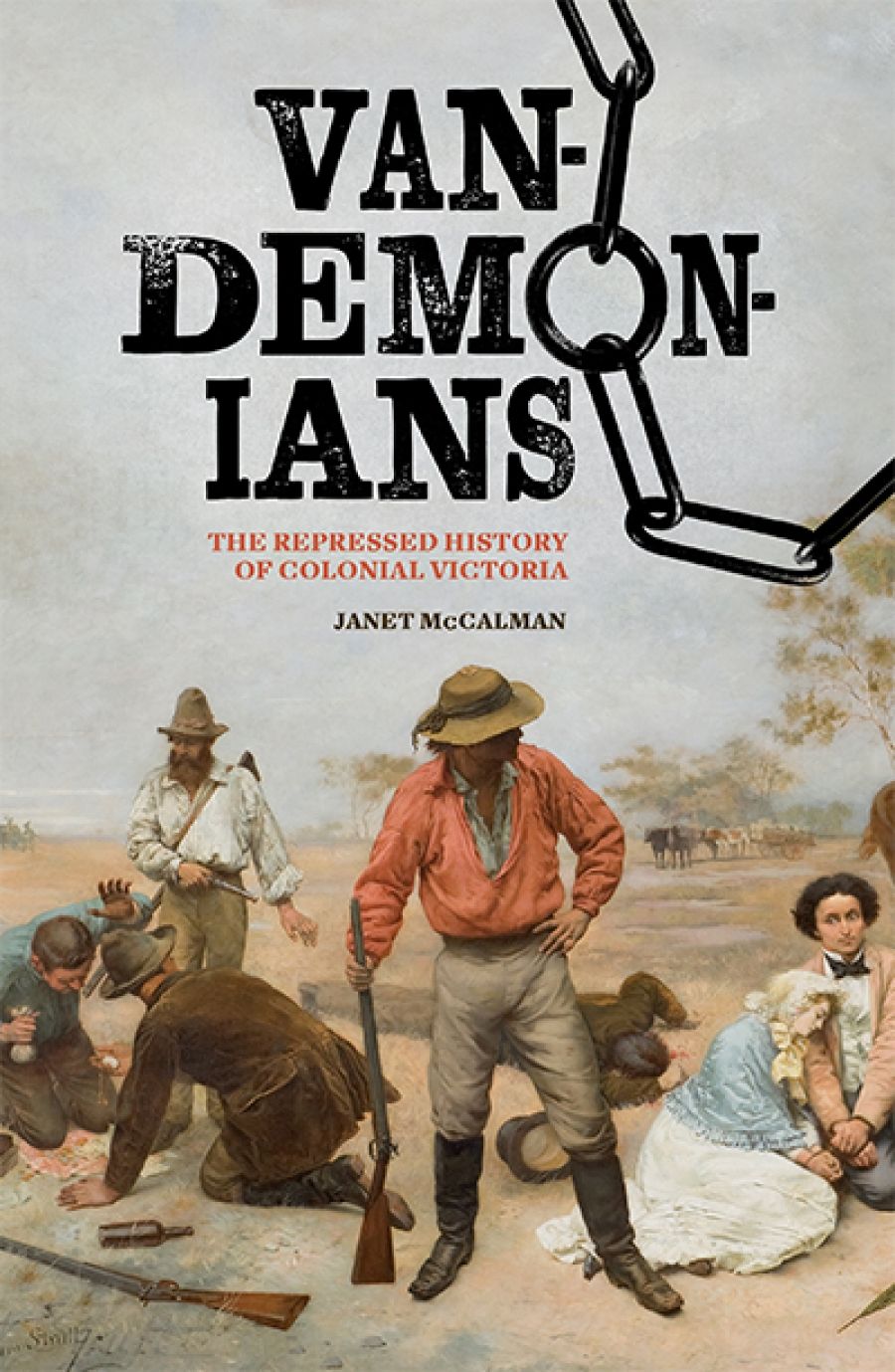

- Book 1 Title: Vandemonians

- Book 1 Subtitle: The repressed history of colonial Victoria

- Book 1 Biblio: The Miegunyah Press, $39.99 pb, 343 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/b3PR9b

McCalman’s new book, Vandemonians, is a harbinger of the new ways. Her title was the word used in the later colonial period for men and women who had been convicts in Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) during the fifty years of penal transportation (1803–53). That name, with its partly ludicrous, partly diabolical connotations, was pinned with easy contempt on those who made their way across Bass Strait, mainly to the province of Port Phillip (afterwards Victoria), but also to South Australia.

Its subtitle calls this book a ‘repressed history’. Victoria has always prided itself on being free of the ‘convict stain’. And yet, not only did transported individuals make their way there from the settlements around Sydney, but at least thirty thousand more, possibly half of all the men and women sent to Van Diemen’s Land, crossed from the south. At any point before the 1860s, they add up to a substantial minority of the European population of what was to be Victoria.

The long-term demographic effect is not so clear. Some Vandemonians crossed back. Also, the overall gender imbalance among the settler population meant that, wherever they ended up, relatively few left lasting families. However, foundations make a difference to superstructure, and in various intangible ways the Vandemonians left a lasting impact.

The Vandemonian heritage was ‘repressed’ for another reason. A reliable and detailed account such as McCalman offers has only been made possible by the skilled work of large numbers of people over several decades, beginning in the 1970s, and it has only reached its present state because of online resources and related statistical techniques.

The word ‘panopticon’ echoes through the book. In England in the 1790s, the great penal reformer Jeremy Bentham had invented the original panopticon, an ideal and at that point theoretical prison with the cells arranged so as to make every inmate visible at every hour of the day and night from some central point. As someone said at the time, it was a sort of glass beehive. In principle, every human movement could be watched and every individual thoroughly known from the moment they entered their cell to the moment they left it.

Bentham’s panopticon was to be a building. It was to embrace body and mind at the same time. McCalman spells out two other kinds of panopticon. The post-Bentham generation created a vast penal bureaucracy, a paper panopticon, so as to maintain a centralised record of every convicted criminal from original crime to liberation, often including personal and family details from earlier and later life. The most remarkable early example of a paper panopticon was worked out in Van Diemen’s Land during the transportation period. However, in Victoria, it was matched in efficiency, if not in purpose, by the demographic data-collecting developed in the 1850s by W.H. Archer, colonial registrar-general. McCalman calls Archer’s creation ‘the best vital registration regime in the English-speaking world’.

More recently, the family-history industry has made its own massive contribution to our detailed knowledge of the past. That has now been combined with convict records so as to create several databases, and all within an unusually powerful digital humanities project. In other words, the work in this book rests on a combination of the bureaucratic ingenuity of the early nineteenth century and the electronic ingenuity of the twenty-first, the paper panopticon finding fruition in a digital panopticon.

McCalman has humanised the data by telling the stories of a little over two hundred men and women. One woman in particular, Ellen Miles, weaves her way through the book, much as she seems to have done through the system that shaped, or failed to shape, her life. Arriving in the early pages, she leaves at the end, meanwhile turning up in a series of locations, from central London to Ballarat. In a proper panopticon no one can answer back, and yet Ellen Miles managed it. An enigma from start to finish, she stands out as a poke in the eye, all-seeing or not, of Jeremy Bentham.

McCalman made her name with Struggletown (1984), about life among the poor in inner-city Melbourne during the first half of the twentieth century. More recently, she has been a public-health historian in the University of Melbourne’s School of Population and Global Health. She therefore has unusual expertise for an Australian historian and there is much that is new about this book. Interwoven with genealogical and biographical detail of a familiar kind, she asks questions about physical health and circumstances, not only during individual lives, birth to death, but also from parent to child, and over several generations.

The capacity to hold onto so many lives so fully over time is what really makes the book stand out. Our knowledge of any other individual over time is something qualitatively different from knowing them in a snapshot way. Novelists know that. I doubt whether Jeremy Bentham had much literary imagination, but among the makers of the paper panopticon there must have been some who enjoyed the chance of entering in this way, diachronically, into the lives of others. There might also have been, even then, a particular interest in joining the dots from each early life, even pre-birth, to behaviour and experience later on.

McCalman makes a great deal of the interconnection of health, family, individual background, and ability to manage fortune and misfortune. She mentions physical appearance, beginning with weight at birth, as evidence of the combined impact of these things. The overall burden of the book is somewhat fatalistic. Children are justifiably understood to be more or less affected by family trauma, so that difficulties affecting one generation are passed on to the next. So we hear of ‘the transferring of violence and substance abuse down the generations, and the cost in human life [likewise transferable] of extreme poverty, marginalisation and neglect’. Intergenerational trauma creates particular attitudes to authority, dependence, sense of entitlement, resentment, and much else, all mixed up together.

All this makes for a remarkable response to the kind of questions that can be usefully asked about the early invasion period in Australian history. There is one qualification McCalman doesn’t mention. Her convicts typically arrived in or after the 1820s, and until then there seems to have been general agreement among contemporary observers at the time that the children of convicts were quite unlike their parents. Typically tall and healthy, they seemed keen to do well. Why the apparent difference with later?

It was not because of a super-careful government. During the twenty-year war with France, no more than a few hundred convicts had arrived each year. Subsequently, it was several thousand, up to seven thousand in 1833. Numbers surely made a difference to the whole exercise. In the later period, some of the mighty anonymity of British city life, such as Charles Dickens penetrated in his stories, was transferred to the antipodes. The paper panopticon was designed to deal with it, labelling each wandering soul. Individuals cannot matter in quite the same way when numbers are vast. This book is part of a long effort to make them matter.

Comments powered by CComment