- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Selected Writing

- Review Article: Yes

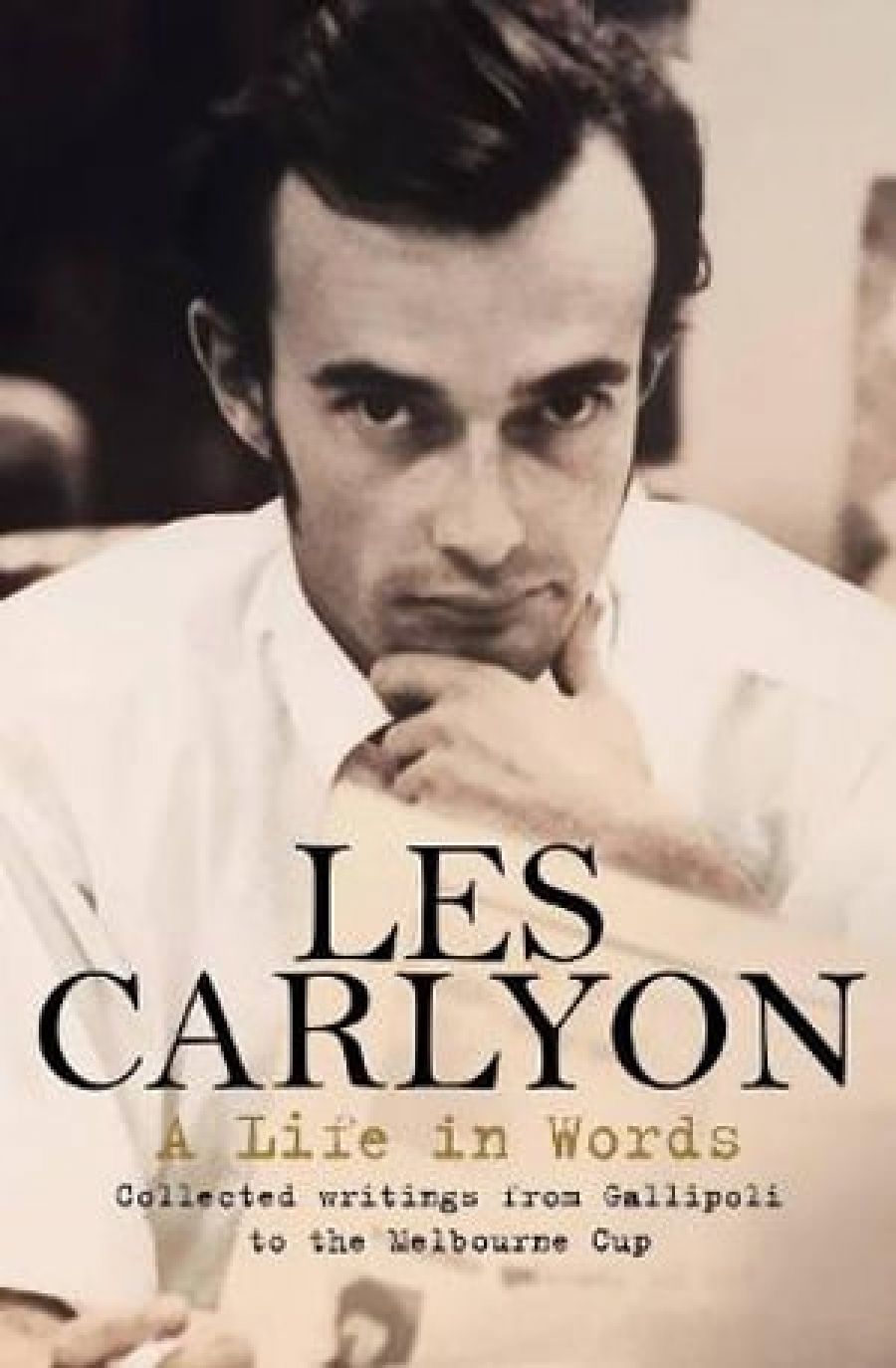

- Article Title: A venerable wordsmith

- Article Subtitle: Taking a punt on Les Carlyon

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I guess every reviewer comes to a book with expectations, especially when the author’s reputation precedes him or her. On opening this collection, I knew that Les Carlyon (who died in 2019) wrote well. I remember my parents reading him in The Age and murmuring approval of his lyrical style and, sometimes, the content. I knew he loved horses, the track, and the punt. To me these were disappointments to overlook: I have hated horse racing since I was a kid driving around with my grandfather in his Datsun, windows up and the races on. My grandfather never wound down the windows, presumably so he could hear the call: perhaps it was the lack of fresh air that poisoned me against the sport. And I knew that Carlyon had written huge tomes on war and the Australian experience: Gallipoli (2001) and The Great War (2006) won acclaim, sold well, and left some military historians with reservations about his scholarship. My expectations, mostly, were realised. I sped through A Life in Words, encountering witty and whimsical delights along the way.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Seumas Spark reviews 'A Life in Words: Collected writings from Gallipoli to the Melbourne Cup' by Les Carlyon

- Book 1 Title: A Life in Words

- Book 1 Subtitle: Collected writings from Gallipoli to the Melbourne Cup

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $39.99 hb, 464 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/mgZZD7

The collection is organised into nine thematic sections: history, war, politics, culture wars, satire, sport, literature, business, racing. Some collections feel arbitrary, but not this one: the pieces are chosen judiciously and form a coherent whole. A few of the pieces run to several thousand words, but most are much shorter, some no more than a comment or an observation.

The book stands as a tribute to Carlyon’s skill as a wordsmith. Such was his ability with the pen that he could persuade the reluctant as well as the faithful to accompany him. An article on Hirohito printed shortly after the emperor’s death in 1989 is entitled ‘Hirohito: Each-way Punter’. That subtitle would have convinced a fair few ex-servicemen to put aside decades of hurt, for a moment anyway, and read on. Carlyon’s sentences are short, smooth, and clear. Some linger in the mind, such is their cadence and the elegant economy of their construction. It is no surprise to learn that among the writers Carlyon most admired were Henry Lawson, Geoffrey Blainey, and Don Watson. Evidently, he followed George Orwell’s encouragement to shorten and simplify. For me, the book prompted as many thoughts about the purpose and demands of writing as it did about the topics discussed.

Carlyon’s main subject was Australia. He had an eye for character – of people, institutions, and nation – and the patience and skill to describe what he saw. The focus on character gives the collection its glue, uniting a disparate and sometimes unlikely group of subjects. An article on Paul Keating’s rhetoric and use of language is followed by a study of Jeff Kennett, whom Carlyon depicts as a bundle of manic energy and maddening contradictions. An article on the ‘patrician’ Robert Holmes à Court sits comfortably next to a piece on Lang Hancock, like Holmes à Court a wealthy Western Australian magnate but never a patrician. A review of Bob Hawke’s memoir bothers little with the former prime minister’s words, dwelling instead on ego: ‘Here is a finer romance than Bob and Blanche. Here, laid bare, is the great love of Hawke’s life: himself. Without demur, he can hint at his genius.’ The writing on Australian politicians is among the best in the book.

Less engaging are the articles on Australian military history. On the evidence presented, Carlyon subscribed to what might be called the Australian War Memorial school of military history, replete with ‘you beaut’ Aussie diggers, useless Poms, and honourable Turks. In an article on the ‘culture wars’ he expressed distaste for revisionism, which ‘restocks history not with people – flawed, human and interesting – but stereotypes’. Revisionism for its own sake is indeed tiresome, but done right it isn’t about stereotypes: it entails asking ourselves what we have got right and what we have got wrong about our history, a vital and continuing task. Did Carlyon’s work on war ask this? In this field it was his work that lent on stereotypes. It is telling that two of the back cover puffs come from John Howard and Peter Cosgrove, traditionalists to the core.

Carlyon was sure about his vision of Australia. That vision could be found in a past that, while not perfect, was not for us modern types to question or reproach. Bill Gammage once wrote that the trouble with Anzac as a national tradition is not that it looks back, but that it doesn’t look forward. I’m not sure that would have bothered Carlyon, be it Anzac or any other organising tradition. Sometimes his certainty about the good and bad in Australia manifests itself as unedifying sarcasm. He takes aim at modern government bureaucracy with a cheap, needless gag about the equal representation of women and Indigenous Australians. It’s the joke of someone who has never had to worry about his place in the world. ‘Gay whales’ are the hook for another attempt to poke fun at modern concerns and sensibilities. Conservationists guilty of nothing more than earnestness are presented as cranks. On the environment, the message must always matter more than the messenger, a point Carlyon missed. This streak in his writing has been described as irreverence, the words of a man battling the cant of the priggish and po-faced. It reads more like a sneer. The best that can be said is that he should have left the satire to others.

This collection is a gratifying and occasionally exasperating read. Perhaps this is what made Carlyon so good and brought him a large and loyal following. He can give you the irrits and still make you want to go on reading. Annoyingly, I even enjoyed the bits about horse racing.

Comments powered by CComment