- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Carnage in Portsea

- Article Subtitle: The mirror of crime in Garry Disher’s latest novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A year before his death in 2015 following a cancer diagnosis, the writer–playwright Henning Mankell responded to a question about his love of the crime genre. He stated that his objective was ‘to use the mirror of crime to look at contradictions in society’. Mankell’s mirror was evident in his Kurt Wallander series (1991–2009), in which the detective was faced with contradictions not only in the landscape of crime and murder but also in his own domestic life. Great crime fiction does not need to focus a lens on the overlapping worlds of the private and the public. But well written, the genre’s interconnected spheres address the moral complexities that drove Mankell’s passion for crime fiction.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Tony Birch reviews 'The Way It Is Now' by Garry Disher

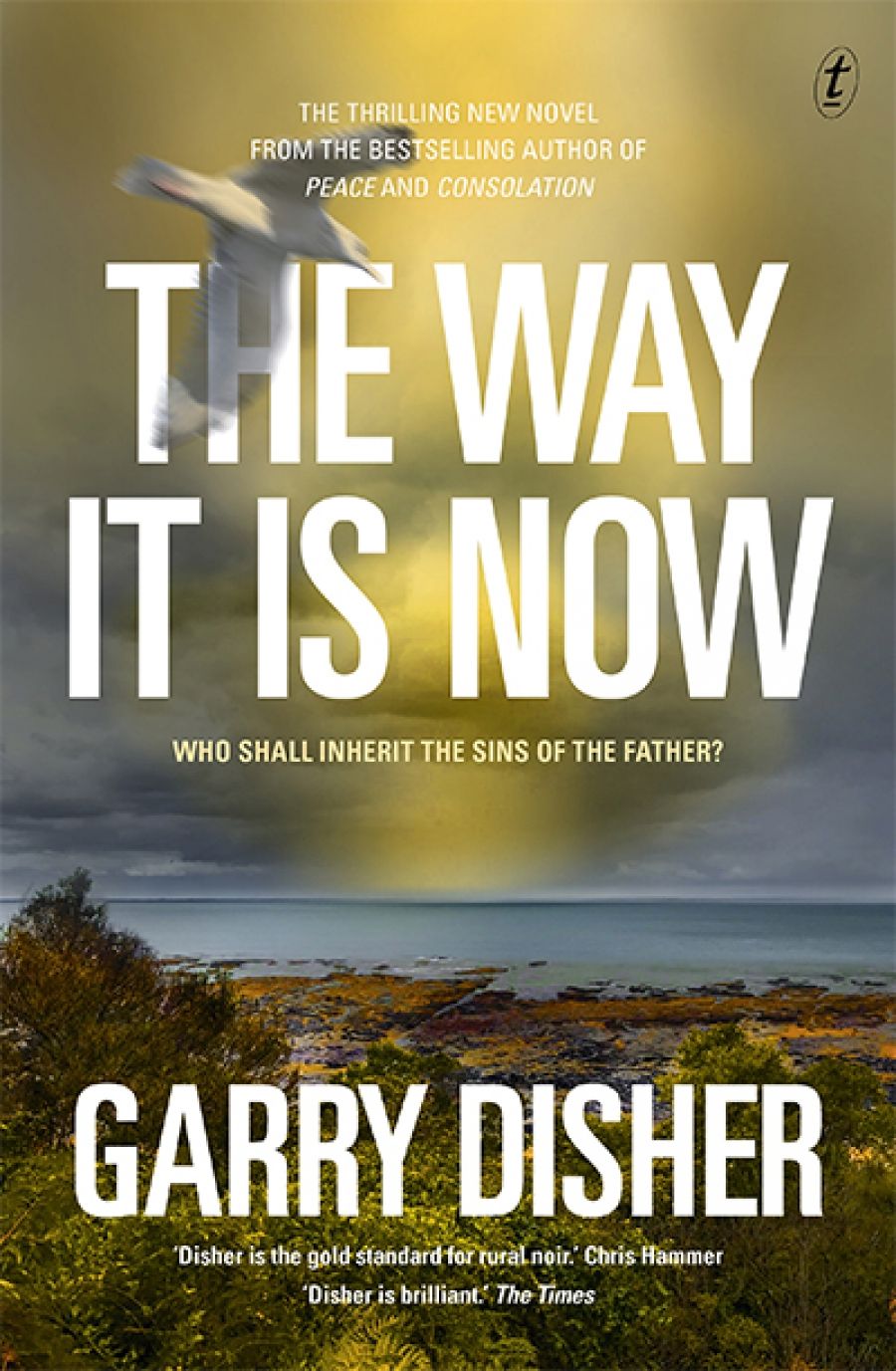

- Book 1 Title: The Way It Is Now

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $32.99 pb, 281 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/gbqyz0

Garry Disher, a prolific writer of both crime and general fiction, has always been concerned with the domestic lives of his cops, but also his victims and villains. He has won many prizes for his work, deservedly so. Beginning a new Disher crime novel is an act of both familiarity and surprise. The Way It Is Now welcomes readers back to the terrain of Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, following the conclusion of his Hirsch trilogy (2013–20), which is set in South Australia. We spend little time on the front beaches of Port Phillip Bay, or along the playgrounds of Sorrento and Portsea, where space is contested between new and old money. Disher’s crime scenes are the back blocks of the peninsula, the fibro shacks, boat yards, and deserted roads of the less well off. Violence, murder, and deviance abound.

The central character of the new novel is Charlie Deravin, who, like his father, is a career policeman. Following an indiscretion, Charlie is on enforced leave from the sex crimes unit. He, as with the police who have come before him, is wonderfully crafted by Disher. Charlie appears to be a decent man, but one who has been worn down by his job and his personal life. His wife having left him before the novel’s opening, he is back living in the family home, a run-down holiday shack riddled with asbestos, while awaiting a hearing on his suspension. He has little interaction with others, apart from occasional visits from his daughter, Em, and a new girlfriend, Anna.

Being back on home turf conjures traumatic memories and ghosts for Charlie, in particular the puzzling disappearance of his mother, Rosie, many years earlier. Her car is discovered damaged and abandoned early in the novel, along a ubiquitous Disher backroad where trouble often lurks. Around the time of Mrs Deravin’s disappearance, a boy vanishes from a nearby beach in equally mysterious circumstances. Neither the woman nor the child has been seen since. Years later, the discovery of skeletal remains produces a fresh investigation.

To exacerbate matters, Charlie’s father, who was a serving policeman at the time of his wife’s disappearance, remains a prime suspect. Soon after her disappearance, he married the woman he had been in a relationship with, an act that many regarded as callous and highly incriminating. The suspicion surrounding Charlie’s father extends to the homes, walking tracks, and beaches of the locale itself. While not quite a police town, the area inhabited by Charlie’s family attracted other police, both serving and retired.

The environment has created socially incestuous relationships, with some cops looking out for each other, while the concerns of others are driven by unease and paranoia. Examining the insular culture of the police force has been another staple of Disher’s fiction, and it is deployed here to great effect. The lives of his characters are governed by both fierce loyalty and the ever-present menace of corruption. The impact of this binary on Charlie Deravin pervades The Way It Is Now. He understands that he needs to be able to trust someone if he is to discover the truth behind the disappearances, but he doesn’t know whom to trust.

An early suspect, after Rosie Deravin vanishes, is Shane Lambert, an itinerant worker who had been renting a room from Mrs Deravin following her separation from her husband. Lambert shifts from being prime suspect to red herring and back again several times throughout the novel, as do other characters in an ensemble cast, both friends and enemies of Charlie. Disher does not introduce us to the domestic relationships of the key protagonists as a form of relief. Those close to danger, particularly Charlie’s loved ones, inevitably face danger themselves. The disappearance of Charlie’s mother is directly linked to her care and concern for others.

Each summer I see people lying by public swimming pools, or in the sand on beaches, sometimes along the Mornington Peninsula, reading crime fiction. Readers often tell me they enjoy the genre as ‘light relief’, a puzzling response considering the endlessly macabre ways that crime fiction writers concoct new ways to torture, murder, and dismember characters. A Garry Disher novel is never an exercise in light reading. He respects the genre and his readers. His novels can also disturb a reader, for his characters are quite ordinary people, in the best sense. They are men and women like you and me – characters capable of good and bad, courage and murder.

Comments powered by CComment