- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rachel and Hannah

- Article Subtitle: Inga Simpson’s post-apocalyptic new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Rachel isn’t the last woman in the world, but she might as well be. Cloistered in her bushland home on Yuin country, in New South Wales, Rachel’s days consist of birdsong, simple meals prepared from a pantry stocked with home-made preserves, and glass-blowing in her private studio – a craft that is both her livelihood and her religion. It’s a peaceful yet precarious existence. The land is scarred by bushfires. Rachel’s senses are attuned to the absence of wallabies and small birds. For all her proficiency with sourdough starter, Rachel isn’t self-sufficient. Her older sister, Monique, provides an emotional tether to the world, while townswoman Mia delivers supplies and transports Rachel’s glassworks to a gallery. When Mia fails to show, Rachel rues the lack of a back-up plan. When Hannah, a young mother, raving about a nation-wide outbreak of death, arrives on her doorstep with a sick infant, luddite Rachel must choose between taking Hannah’s word for it or rejecting her.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Laura Elizabeth Woollett reviews 'The Last Woman in the World' by Inga Simpson

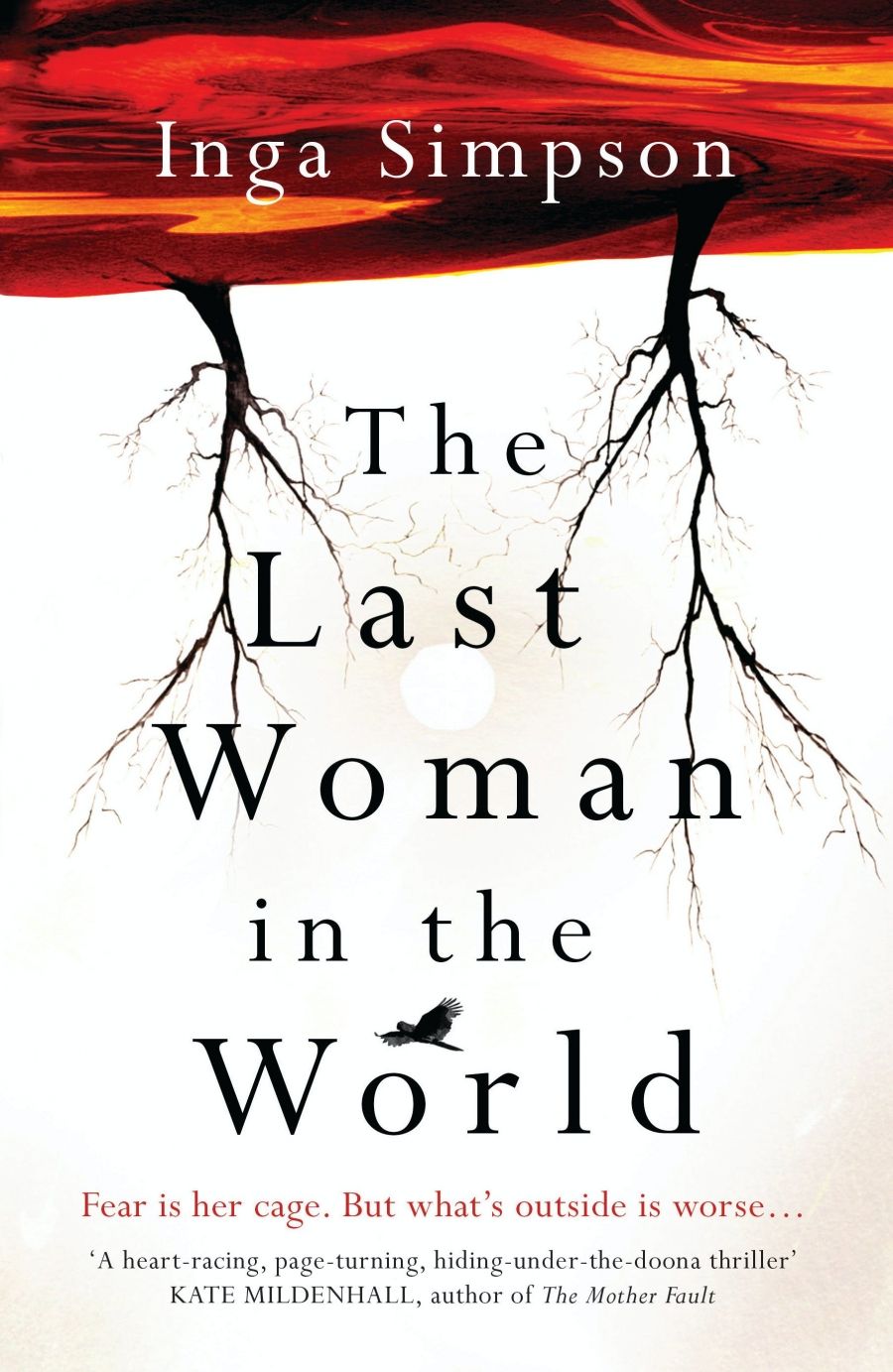

- Book 1 Title: The Last Woman in the World

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $32.99 pb, 344 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/e4edzj

The Last Woman in the World is Inga Simpson’s fourth novel and sixth book, following on from a backlist that includes 2014’s Nest and Understory (2017), a tree-change memoir. Simpson’s trademark preoccupation with the rhythms of hinterland life is evident throughout her latest work, yet with its doomsday horror setup, The Last Woman in the World places Simpson in the company of other white Australian women, like Briohny Doyle, Kate Mildenhall, and Laura Jean Mackay, responding to the spectre of social and environmental collapse on stolen land.

While the near-future of The Last Woman in the World is readily recognisable – bushfires, pandemics, right-wing extremism – the mechanisms of the death-plague remains vague. ‘Another pandemic?’ Rachel presses Hannah for an explanation. As the women and baby Isaiah hit the road in search of medicine and, later, surviving relatives, there are some moments of genuine horror, such as the discovery of the corpses of Rachel’s commune-dwelling neighbours and an encounter with a mentally unstable survivor on the road into Canberra. Yet Simpson’s decision to keep the descriptions and terminology surrounding the plague indefinite – characters refer to the death-causing forces as ‘they’ throughout – makes it difficult to imagine. Perhaps this conceptual uncertainty is realistic, reflecting the confusion of Simpson’s characters as they navigate a rapidly changing world without the language to define it. Occasionally, this has the effect of obscuring the threat rather than amplifying it.

Inga Simpson (photograph via Hachette)

Inga Simpson (photograph via Hachette)

The Last Woman in the World isn’t just another doomsday novel. It’s the story of Rachel, a sensitive yet hermetic woman, and the ramparts of isolation and routine she has constructed around herself. The puzzle of Rachel’s reclusiveness, and the fragility at the heart of it, makes for compelling reading. Simpson is careful to avoid either lionising or pathologising her protagonist, instead presenting a portrait of a conscientious, wounded individual and the traumas, ambitions, and disappointments that have shaped her.

Rachel’s artistic eye animates the narrative, offering respite from the horrors she encounters, as well as raising questions about what it means to create art in a post-apocalyptic world where an audience may no longer exist. On the road, Rachel longs for her studio. Lorikeets are ‘little rainbows … more beautiful than anything she could make’; coloured river stones make her wonder ‘how to achieve that effect with glass’; the sight of Hannah breastfeeding reminds her of a life-drawing class she took as a student. In a powerful scene towards the novel’s denouement, Rachel is confronted by a public art installation she was involved in creating.

Although Rachel bemoans the ‘complex moral decisions’ introduced by the arrival of Hannah and Isaiah, there is an inevitability to her joining forces with the mother and child. Hannah is a sympathetic presence from the start, challenging Rachel’s habits and self-perception. ‘I hear you talking to yourself, you know,’ the younger woman admits, revealing that Rachel’s internal monologue isn’t quite so internal. This memorable moment reveals the toll that Rachel’s seclusion has taken on her social skills.

Beyond being a foil to Rachel’s solitude, Hannah’s significance is largely reliant on the vulnerability and high stakes inherent in motherhood in a post-apocalyptic environment. Though there are flashes of agency, important questions about Hannah’s inner life seem unexplored. We learn that she is in her early twenties, that her pregnancy was unplanned, and that she didn’t expect motherhood to be so ‘hard’. Yet her feelings about bringing a child into such a world, and motivations for doing so, remain opaque. In a novel so concerned with women’s lives and survival, this feels like a missed opportunity.

There is tension in the ambiguity of Rachel and Hannah’s nascent relationship. Is their bond filial, sisterly, or even potentially romantic? That much of this tension is unresolved isn’t detrimental to the narrative. Yet the generation gap seems understated – it’s clear that Rachel is older than Hannah, but not by how much – and, probably due to an absence of cultural signposts, Hannah isn’t wholly convincing as a twenty-something. Given the near-future setting, Simpson’s choice not to anchor her characters in time is understandable, but it can entail a certain loss of texture.

The third act, in which the characters encounter a group of survivors, is a change of pace from the effective slow-burn of the earlier sections. Simpson’s skill as a horror-stylist is most striking when juxtaposed with her eye for beauty, be it natural or man-made. The end of the world, and what outlasts it, is a continually rich subject, and The Last Woman in the World – though uneven – is both thrilling and thought-provoking, offering an urgent evolution of Simpson’s ideas on art, nature, and individual responsibility.

Comments powered by CComment