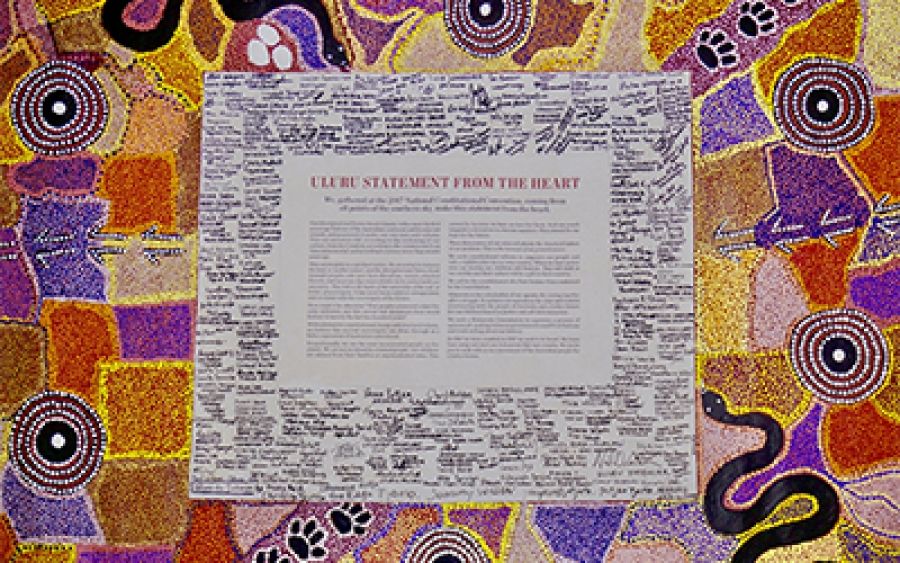

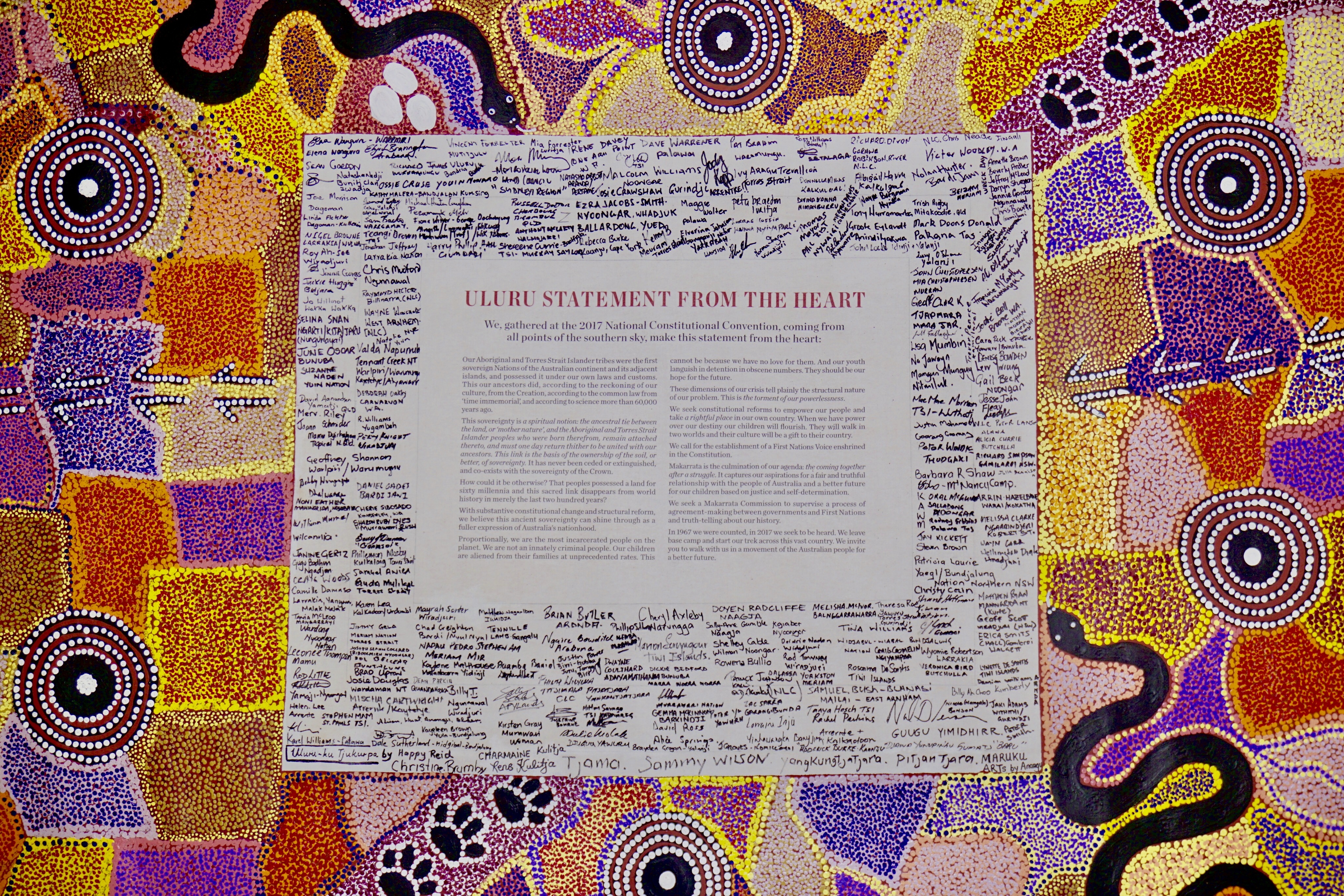

In early 2021, the Victorian government announced the creation of the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission to investigate the harms done to Aboriginal people through colonisation. Named after the word for truth in the Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba langauge, Yoo-rrook will be the first exercise of its kind in an Australian jurisdiction and one of the most significant responses yet offered to the call for Voice, Treaty and Truth issued by the Aboriginal peoples of Australia in the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’.

The Andrews government, having quietly over the past two years progressed its proposal for individual Treaties with each of the First Nations of Victoria (followed by an overarching Treaty), has now turned to truth-telling to guide the process of decolonisation and help determine reparations for past injustices. It is a courageous move, burdened with great expectations. Inspired by the internationally renowned South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and a subsequent iteration in Canada that focused on the genocidal effects of the residential schools system, Yoo-rrook stakes the future of the Aboriginal–settler relationship in Victoria on a painful confrontation with the truth. All of which raises the question: what exactly can (and what exactly does) truth-telling do?

Yoo-rrook, like all public exercises in truth-telling, is premised on two basic assumptions: that there are things not yet known (or not yet widely known) about the past; and that knowing those things will have a transformative effect. The first premise seems hard to dispute, even though ignorance has long since run out of excuses in Australia. Due largely to the dedication of activists and scholars, the story of Aboriginal societies and the damage done to them through colonisation has now well and truly emerged from what W.E.H. Stanner called ‘the great Australian silence’. After the land rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s, prior occupation by organised political societies became much harder to ignore. But it is particularly since Mabo, and the recognition of native title in the common law, that we have seen a culture of recognition displace a culture of forgetting in our political institutions and everyday lives. Though always at risk of becoming trivialised, Acknowledgment of Country has become the daily ritual that returns dispossession to consciousness and offers a glimpse, however brief and narrow, of another history and a different law. And yet, like a curtain that falls after every performance, that great Australian silence has an uncanny way of reimposing itself. Unless things are said again and said anew, the public seems to drift back into a happy forgetfulness.

The very least that can be said about the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission is that it will be another jolt to consciousness and another unsettling of the narrative of peaceful settlement. One of the lessons derived from truth-telling exercises around the world is that there is nothing quite like testimony to bring history home. Carried into the emotional, fully embodied register of the first person, the truths of the past lose their abstract quality and become powerfully affecting. Yoo-rrook, as Stan Grant has noted, will provide a ‘long overdue opportunity’ for Aboriginal people to tell their stories and to speak of their experience of colonial violence (‘of massacre and rape and theft of land’) and, perhaps even more importantly, of their resilience in surviving and reviving through it.1 For those giving testimony and those bearing witness, it promises to be a highly charged and potentially life-changing event. And while there is an argument to be made that truth-telling would be more politically effective if it were instituted at the national level, the provincial character of the Yoo-rrook Commission will have its advantages. In line with the local responsibilities exercised by First Nations peoples, it will ensure that their stories are heard in the places they have been lived and where calls for treaties and reparations must find their justification.

However, it would be naïve to think that Yoo-rrook will completely clear up the past or remove all the obstacles standing in the way of a better future. ‘Mature societies,’ suggests Ian Hamm, a Yorta Yorta man and chairman of the First Nations Foundation, ‘own their entire history. We don’t get to pick the bits we like, we must own the lot.’2 He’s right – taking responsibility for the past is a mark of maturity because it requires a society to interrogate the selective nature of its own remembering and open itself up to the inconvenient (for want of a better euphemism) experiences of others. But history is not like a great story book to which one simply adds missing chapters until the tale is complete. Tied, as are all forms of social knowledge, to differences of perspective and asymmetries of power, history is invariably a site of political contestation and competing narratives. In this domain, ‘truth’ can meet resistance, not simply in the form of lies or denials (though it has those to contend with too), but in the form of ‘other truths’. By creating a stage for Aboriginal voices, Yoo-rrook will expose the general public to another, still largely hidden and still deeply unpalatable, truth. But since they too will have a perspective on the matter, there is no guarantee that they will listen to or accept it.

‘Mature societies own their entire history. We don’t get to pick the bits we like, we must own the lot’

This brings me to the second premise: that truth-telling will have a transformative effect. Like the public exercises in truth-telling undertaken in South Africa and Canada, the great promise of Yoo-rrook is that it will interrupt two processes that, left to their own devices, threaten to run on endlessly: the process of intergenerational trauma and the process of colonial extermination. As the recently appointed Justice Commissioner, Sue-Anne Hunter, noted earlier this year, ‘We as Aboriginal people conduct truth-telling so our children don’t have to carry the weight of the past into their futures.’3 As a Wurundjeri and Ngurai Illum Wurrung woman who is a recognised leader in trauma and healing practices, Hunter is as well placed as anyone to confirm what trauma specialists like Dori Laub have long maintained: namely, that ‘one has to know one’s buried truth in order to be able to live one’s life’.4

At the same time, Yoo-rrook is seen as a means by which the process of colonisation, relentless in its appropriation of Aboriginal land and destruction of Aboriginal life, might finally be arrested. Functioning, as Marcus Stewart, the co-chair of the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria, has put it, as the ‘why’ behind the treaty’s ‘what’, Yoo-rrook is expected to play a crucial role in revealing why the relation between first and second nations must be a ‘sovereign-to-sovereign’ relation that secures Aboriginal people against the kind of arbitrary exercises of governmental power that led to the Stolen Generations.

High expectations, especially in this area of public policy, are hardly to be discouraged. But the experience of public truth-telling in the countries Yoo-rrook references as a model suggests that they are likely to be disappointed, at least in part. Although there were a number of (endlessly recited) stories of healing and recovery at the South African TRC, it was ultimately unclear whether the experience of testimony broke the transmission of intergenerational trauma or compounded it. Here, too, one must contend with differences of perspective and the sheer variety of what the South Africans called ‘personal truths’. But the judgment upon the hearings issued by Nomfundo Walaza, long-term director of the Trauma Centre for Survivors of Violence and Torture in Cape Town, is itself a painful truth that commands attention: ‘the pain of blacks is being dumped into the country more or less like a commodity article – easy to access and even easier to discard’.5 A similar sense of ambivalence and disquiet surrounds claims that truth-telling has the potential to stem the relentless destruction of Indigenous societies. Though by no means wholly scathing, critics of the Canadian TRC suggested that it had in fact approached the process of colonisation as if it were already over. Angry and resentful at the ongoing destruction of their way of life, Indigenous survivors were treated as though their suffering was nothing but the traumatic legacy of a historical wrong.6

One of the difficulties with challenging truth-telling, of course, is that it seems self-evidently right. On what grounds could one be against it? Credit must thus be given to Wiradjuri man Stan Grant for having the courage to pose the question that, at this particular juncture, edges towards the impolitic. ‘The Yoo-rrook Justice Commission,’ he writes, ‘has been praised as an important step to facing up to a brutal history. But is it?’7 Grant’s equivocation is built upon critiques of reconciliation, developed in the wake of the South African and Canadian experiences, that draw attention to the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) pressure it exerts on victims of state violence to forgive and resolve. Now the principal vehicle by which societies revisit the past and move on from it, reconciliation gives victims an opportunity to speak of their pain, but only, it seems, on the condition that they forgo their anger and let everyone escape the prison of the past. In truth and reconciliation, ‘healing’ has come to assume a central importance. But exactly who or what is being healed? Is it Aboriginal people, the relationship between victims and perpetrators, or perhaps, as I have argued elsewhere, the ‘narcissistic wounds’ opened up in settler society by shameful revelations of colonial violence?8

It is, perhaps, because of the elusive nature of healing and the way it imprisons Aboriginal people in the identity of the traumatised victim that Ian Hamm is looking to Yoo-rrook as a way of informing the general public about the ‘strong points’ of Aboriginal culture and identity. ‘The last thing we want from truth-telling,’ he writes, ‘is a story that just paints our history as heartbreak and misery – it must be about the positives and what is unique about the Aboriginal community that the rest of Australia can learn from.’9 That correction, and the sense of balance it looks to achieve, strikes me as vitally important. Without it, Yoo-rrook could easily become another occasion in which Black pain is turned into a commodity article and white Australia repositions itself as the compassionate healer that has always had the welfare of Aboriginal people at heart.

Australia, to be sure, could learn a great deal from Yorta Yorta man William Cooper, who, after hearing of the events of Kristallnacht in 1938, led a delegation to the German Consulate in Melbourne to deliver a letter protesting against the violence. Cooper’s story was widely publicised in 2018 when that letter was finally delivered to the German government by his grandson, Alf (Boydie) Turner. And yet it remains largely unknown in Victoria and beyond. Might that be symptomatic of something? Sadly, as the Adam Goodes saga has recently confirmed, taking a stand against racism has not been ‘our’ forte. Our habit of displacing responsibility to deal with racism onto those who suffer it speaks of a significant blind spot (one is tempted to say black spot) in our political culture. Why is it always incumbent upon Aboriginal people to ‘do reconciliation’ and repair relationships damaged by systemic racism? Why is it up to them to tell the painful stories that return colonisation to consciousness? Could it be that some truths continually elude ‘us’ because of the sense of self they put at risk?

Yoo-rrook could, of course, open our eyes to those truths and catalyse a real transformation. However, it will have its work cut out persuading the general public to see colonisation as a present problem rather than a historical one and as a white problem rather than a Black one. In their response to the Bringing Them Home Report – arguably the closest we have gotten so far to a national truth and reconciliation commission – Australians demonstrated that they were not without compassion for the sufferings of Aboriginal people. Most of us, I like to think, really were sorry. But something happens when the abject Black subject in need of healing becomes the Sovereign First Nations in pursuit of Treaty. That great motto of survival, ‘Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land’, unsettles us to the core. How could it not? We are, after all, a settler society built upon the expropriation of Aboriginal land and the violence to people and culture that was (and is) intrinsic to that expropriation. Of all the truths that Australians are required to face, this one is clearly the most painful – precisely because it has the most significant repercussions. One of the things Yoo-rrook will surely reveal is whether we really are mature enough to confront it.

This article, one of a series of ABR commentaries addressing cultural and political subjects, was funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Endnotes

Grant, S. ‘After the Yoo-rrook Truth and Justice Commission Aboriginal People are not Obliged to Forgive’.

Hamm, I. ‘Truth-telling paves the way to brighter future’, The Sunday Age. 16 May 2021, p. 35.

Hunter, S. ‘Change comes through truth-telling’, The Age, 16 April 2021, p. 21.

Laub, D. ‘Truth and Testimony: The Process and the Struggle’, American Imago, 1991 48(1), p. 77.

Walaza, N. cited in A. Krog, Country of My Skull, London: Vintage, 1999, p. 244.

Coulthard, G. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, University of Minnesota Press, 2014, pp. 105–129.

Grant, S. ibid.

Muldoon, P. ‘A Reconciliation Most Desirable: Shame, Narcissism, Justice and Apology’, International Political Science Review, 38(2), pp. 213–227.

Hamm, I. ibid.

%20copy.jpg)