- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthologies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Preaching to the converted

- Article Subtitle: Burdening literature with moral instruction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sweatshop, based in Western Sydney, is a writing and literacy organisation that mentors emerging writers from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Racism, their ninth anthology, brings together all thirty-nine writers involved in their three programs – the Sweatshop Writers Group, Sweatshop Women Collective, and Sweatshop Schools Initiative.

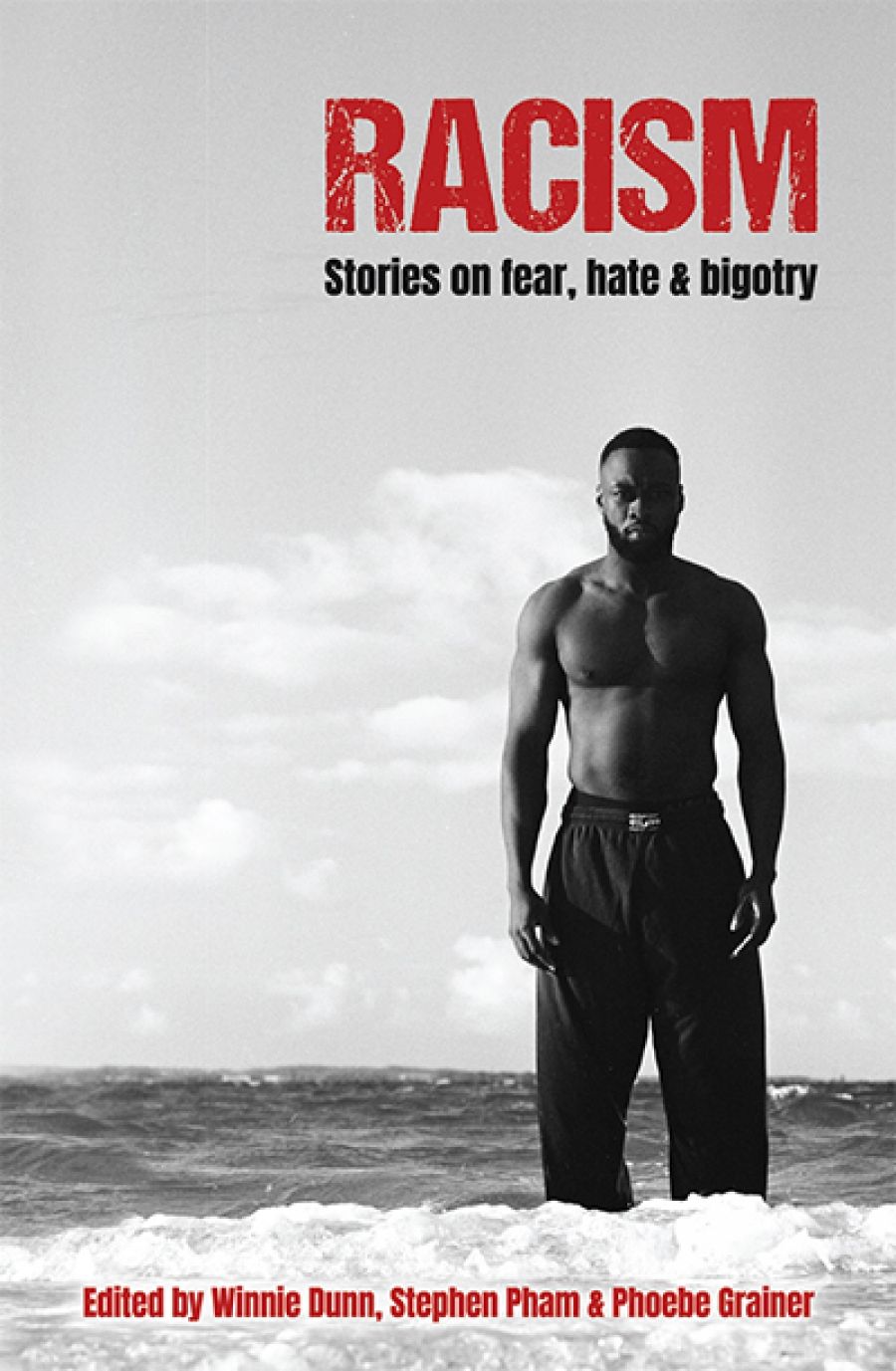

- Book 1 Title: Racism

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories on fear, hate and bigotry

- Book 1 Biblio: Sweatshop Literacy Movement, $19.95 pb, 185 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: www.sweatshop.ws/racism

The racist acts in this anthology are of a predictable kind. Characters are made to feel ashamed by cultural traditions, are interrogated about their mixed-race identities, or are subject to ignorant stereotypes assumed by schoolmates and teachers. While there are exceptions, such as Guido Melo’s ‘Casa Sendas’, Saleh’s ‘Beit Samra’, and Shirley Le’s ‘Looking Classy, What Are You?’, the perpetrators are typically white. Racism is often shoehorned into these stories, appearing in the form of ineffective moral intrusions meant to prompt white readers to reflect upon their own implicit biases. This is not to say that writers of colour should not write about racism. The question is one of audience. I read, incredulously, that in order to ‘set the record straight’, Sweatshop seeks to ‘provide a personal and intimate record from First Nations people and people of colour … that demonstrates the pain, despair, confusion, complexity and rejection that comes with being the “other”’. One might have presumed that asking First Nations people and people of colour to perform their ‘otherness’ to prove a point to white readers is anathema to the organisation’s ethos.

The calibre of the works that appear in Racism is uneven, and the pieces tend to be unpolished. This is to be expected, given Sweatshop’s focus on improving literacy. That said, a more discriminating selection process might have yielded a more successful and robust collection. Some writers show real promise, among them Monikka Eliah, whose young, droll narrator in ‘Superbrow’ stands out, though I suggest that forcing the issue of racism ultimately does these contributors a disservice. Rather than empowering their writers, Sweatshop counteractively encourages them to argue from a position of victimhood, becoming the subject of racism instead.

It is discomfiting to read the stereotypes that proliferate in this book, though not for the reasons one might think. Frequently, it is non-white characters and speakers who rely on the most tired tropes. Janette Chen’s ‘Sydney Asian Limericks for Selective School Gimmericks (with apologies to the Facebook meme page)’ opens with the line, ‘There once was a Chink that cleaned pools’, and is followed by a stanza beginning, ‘The school is a swamp full of Asians / all trained in complex calculations.’ Marginalised groups often successfully reclaim the language of the oppressor. However, when that originally pejorative language is used without any intent to subvert or ironise its meaning, the line between reappropriating and perpetuating a stereotype all but disappears. Elsewhere, in Daniel Nour’s ‘Tournament of the Ethnics’, the narrator’s Egyptian father searches for his mobile phone and becomes ‘Aladdin trawling through a cave of trinkets for his precious lamp’. There is also the awkward language, reminiscent of phrenology, in Tyree Barnette’s ‘Invasions’, where the protagonist compares the Ni-Vanuatu people’s features with his own. The character, who is African American, observes how their ‘rounded craniums framed flattened foreheads that stood over large, filled nostrils; marble-shaped eyes poked forward and fronted an oval head’. Throughout the anthology, noses and foreheads are variously described as ‘sloping’, ‘wide’, and ‘flattened’. Where such language might have been used to address more complex ideas related to beauty standards and internalised racism, it – doubtless unintentionally – evokes the derogatory language historically used against Southeast and East Asian people.

One might expect such an anthology to expand upon and redefine the cultural image of Australia, who a ‘real’ Australian can be, and what they can look like. Instead, it reinforces the idea that to be truly Australian, one must look a certain way. Zoya Dahal refers to herself as ‘yellow-skinned … and nothing like the tall, white, blonde, freckled, flip-flop wearing Australians’. Ayusha Nand, in ‘Melanin’, writes similarly: ‘I don’t feel Australian because I don’t fit the stereotypical Australian look.’ The post-Immigration Restriction Act 1901 dichotomy remains intact in this book: there are the ‘true’, white Australians, then there are those who can never hope to fit in. It also raises questions about why one would want to be defined by what one is not, with its implicit suggestion that people of colour sit in relation to and are defined by their white counterparts.

The most frustrating aspect of Racism is that it represents a missed opportunity. A literary work that addresses racism in contemporary Australia – one genuinely willing to engage with those who deny that discrimination is a serious issue – would be valuable. However, this anthology does not sincerely seek out ‘a serious conversation with Australia about race’. If it did, these writers would not be trotted out to perform their identities so that readers can assuage their ‘white guilt’. While Racism may be an ‘own voices’ endeavour (everything from editorial, to production, to cover design is led by people of colour), the book’s intended audience is anything but. ‘White people love that shit! ’ Rizcel Gagawanan writes in ‘Act Like a Filipino’, a story where an actress makes grotesquerie of her racial identity for a white director.

Aside from questions about how useful it is to burden literature with moral instruction, the fact of the anthology’s contributor list also presumes that all writers involved with Sweatshop wish to write about and be defined by their experiences of discrimination. Would anyone who does not believe in the reality of racism reach for an anthology titled Racism, whose bold opening line is ‘Australia is racist’? The premise is flawed. This is not a book that is seriously intended to change minds. It is for progressive readers who will approach this work with a combination of sympathy, guilt, and voyeurism, and who will praise Racism unquestioningly, lest the word be used against them next.

Comments powered by CComment