- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Watercolour and neon

- Article Subtitle: A cubist anthology of Irish fiction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Back in my bookselling days during the early noughties, I spent a grey London autumn in the company of W.B. Yeats. My employers were Maggs Bros., an old Quaker firm and the queen’s booksellers, then based in Mayfair’s Berkeley Square: a venue that sounds glamorous but wasn’t, or at least not for me. The job involved much sitting in an underheated basement, beneath windows that offered a glimpse of passing ankles, cataloguing my way through stacks that bulged with a collection of Irish literature, predominantly by or associated with Yeats, assembled with frugal determination and frankly insane completism over decades by an autodidact bus conductor from South London.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Sinéad Gleeson (photograph via author's website)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Sinéad Gleeson (photograph via author's website)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): The Art of the Glimpse

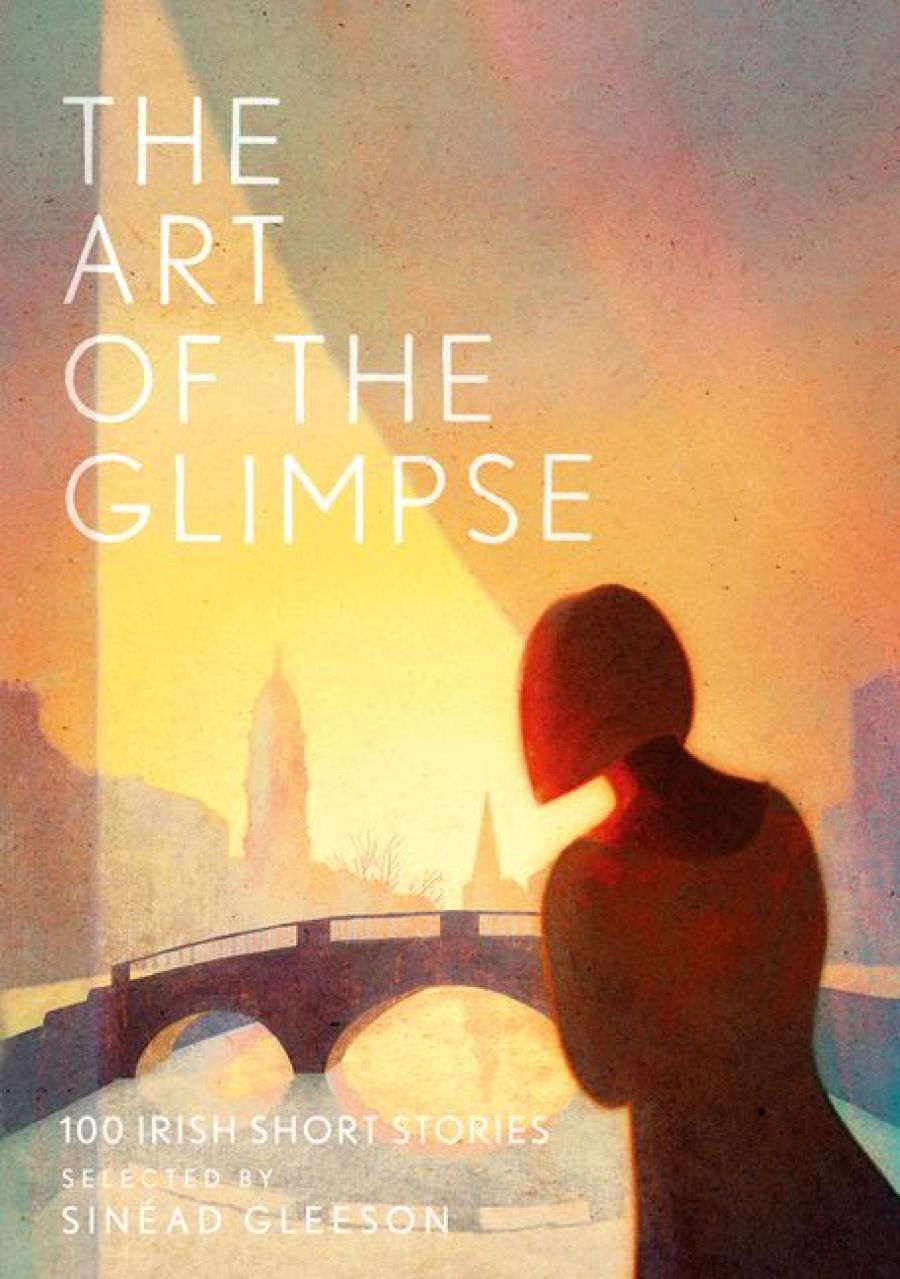

- Book 1 Title: The Art of the Glimpse

- Book 1 Subtitle: 100 Irish short stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Apollo, £25 hb, 766 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/a1KZxj

I tell this story because I know something of what it is to be glutted on the Irish canon. Show me another Abbey Theatre playbill or Cuala Press broadside, another first edition of The Celtic Twilight, and the sweats and nausea will immediately return.

The Art of the Glimpse is an anthology allergic to the traditional contours of the Irish short story tradition. It is designed to democratise and ventilate the canon: to make room for a hitherto (at least to this reader) neglected Irish feminist literary tradition, and to give voice to young and emerging writers, as well as more diverse communities of talent (queer and LGBT+ authors, migrant voices, those with disabilities) and those continually overlooked purveyors of genre fiction.

This expansive view is then solidified by two interesting editorial decisions by Sinéad Gleeson, herself an essayist and short story writer known for two recent anthologies of writing by Irish women. The first is to restrict choice to one story per author, irrespective of canonical heft (so one Beckett, one Joyce, one John McGahern). The second is to order the hundred stories alphabetically by author. So it is that a perfect cut jewel by Elizabeth Bowen about a trip to a milliner adjoins a lurid account of Scaphism by Blindboy Boatclub, one half of an Irish hip-hop duo who appear in public with plastic bags over their heads.

Once you recover from these stylistic handbrake turns, the method works. The overall impression is Cubist, a simultaneous foregrounding of old and new, quiet and loud: rural restraint and urban maximalism, boozy Protestant ascendency charm and bog Irish demotic, watercolour wash and glow-stick neon. Older works borrow some radicalism from adjacent younger writers; new and marginal voices are lent respectability by appearing alongside more established peers. It’s a mash-up method Gleeson perhaps learned from the late David Marcus’s landmark Faber anthologies of Irish lit.

But once the reader has settled in – and lord knows at 750-plus pages there is plenty to settle in for – edgy editorial pyrotechnics give way to the more lasting pleasures of discovery. If novels are the front office of a national literature, short stories are its back gardens seen from a train running along a suburban corridor – privacies glimpsed in passing; a society documented in samizdat form.

And for the non-Irish literary tourist, there are plenty of official expectations to upset. Everyone knows, for instance, that Sheridan Le Fanu – chronologically the earliest author in the collection – is an acknowledged master of the ghost story. Fewer will be aware of how effectively Roddy Doyle can traverse the same ground, as he does in a contemporary tale of a Polish nanny in Dublin, descending into madness thanks to a haunted pram.

Likewise, I had never heard of the Melbourne-born author Mary Bright, who, writing as George Egerton, published some of the most coruscating Victorian-era fictional depictions of female abjection within and without traditional marriage. That she reads like an Anglo-Irish Ibsen or Strindberg is perhaps down to the fact she knew them well. It turns out that she lived in Norway for years and translated Knut Hamsun’s Hunger into English.

Some authors known only to me as novelists are even better in short story form. Eimear McBride, for one, whose rich and endlessly inventive prose can go down like overstuffed fruit cake if read at too great a length, furnishes a five-page lightning flash of a story. ‘Me and the Devil’ is tuned to the same dazzling frequency as Samuel Beckett’s late-career contribution, ‘Ping’.

And then there is Kevin Barry, whose novel Night Boat to Tangier seemed so wonderfully dank with human depravity when it appeared in 2019. That work seems PG when compared with ‘The Girl and the Dogs’, which notates in unsparing detail a dark month of the soul experienced by a crack dealer hiding out in a caravan on a County Galway farm.

Even with its democratic air and inclusive bulk, the collection has its limits. The Queensland-born Francis Stuart, friend to Yeats and husband to Iseult, Maud Gonne’s daughter – a writer whose fiction Colm Tóibín has written of in terms of simple awe – lived to the age of ninety-seven but isn’t present here. That he spent the war years in Berlin broadcasting Nazi propaganda might explain why. He is what Tóibín called a figure of ‘moral awkwardness’.

Nor is the perennially underrated Ulsterman Joyce Cary (remembered, if at all, for his novel The Horse’s Mouth) included. The excavation of overlooked writers that Gleeson has made central to her anthologising is gendered – understandably so, given the historic marginalisation of women in Irish letters. Still, Marian Keyes, who does make the anthology, is one of the most commercially successful Irish authors of all time, while Cary was the laureate of poverty in the service of art.

Whatever individual cavils readers may bring, there is so much that is golden in the Irish short story that The Art of the Glimpse glows with it. The sense it offers of a subtle and damaged people – inhabitants of an anarchic century and its long aftermath, incorrigibly oral, soused in poetry, long trained in turning untenable situations to glorious narrative ends – is on full and prismatic display.

We should be grateful for Gleeson’s efforts at inclusion and historical recovery here, since they have brought to light many authors of talent and significance. It’s an anthology that argues against literary canons remaining too fixed and inviolate. What The Art of the Glimpse suggests, instead, is that canons should be closer to constellations we pick out from the night sky – points we can reshape and sail by, navigating through periods of cultural confusion, torpor, or flux.

Comments powered by CComment