- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Coming together after a struggle’

- Article Subtitle: A process of belated state-building

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

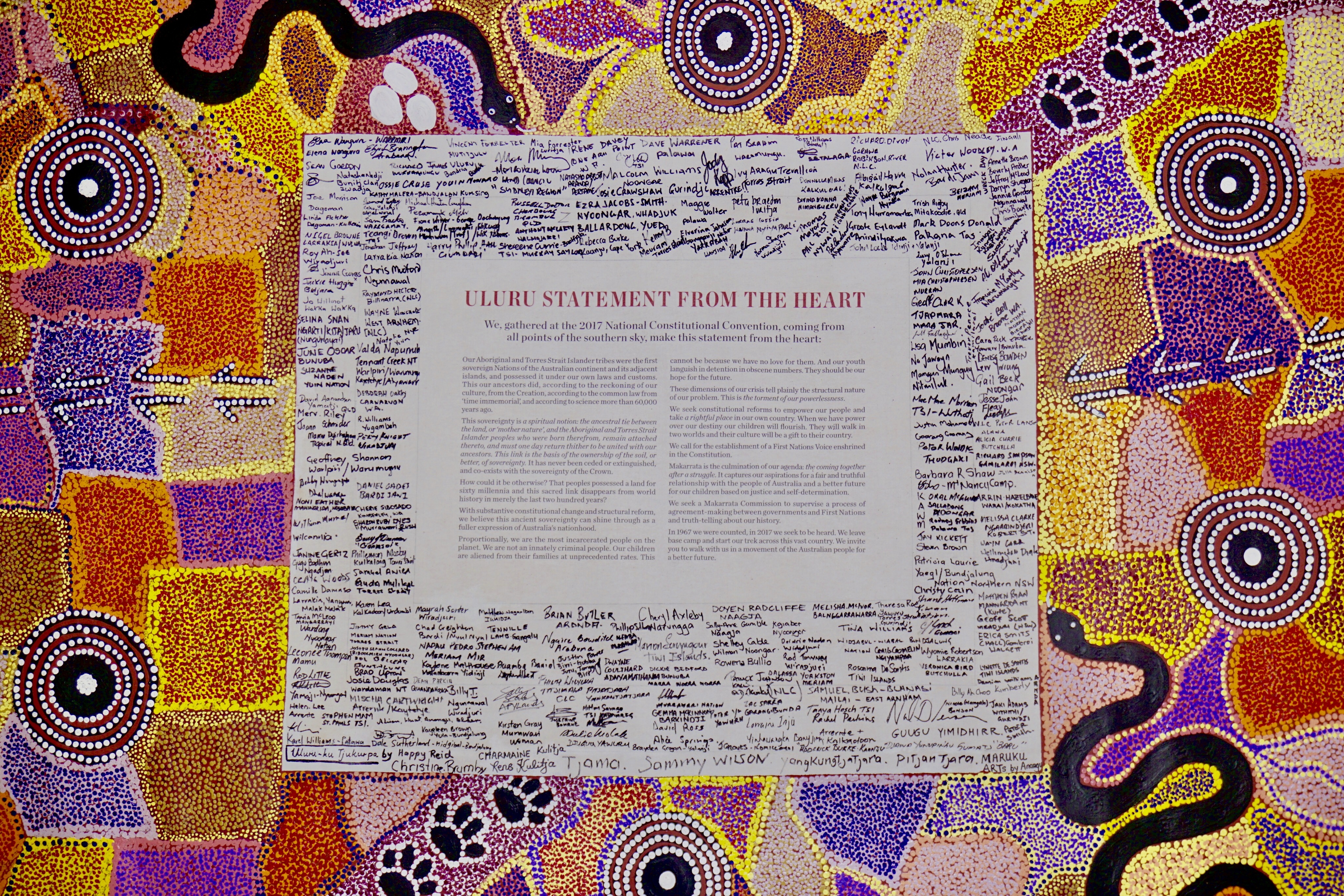

The Uluru Statement from the Heart was made at a historic assembly of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at Uluru in 2017. It addresses the fundamental question of how Indigenous peoples want to be recognised in the Australian Constitution. The answer given is a First Nations ‘Voice’ to Federal Parliament protected by the Constitution, and a subsequent process of agreement-making and truth-telling. This process should be overseen by a Makarrata Commission, from the Yolngu word meaning ‘the coming together after a struggle’. Inspired by the values enshrined in the Statement, Victoria has established such a process through the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission. ‘Yoo-rrook’ is a Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba word meaning ‘truth’.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: The Uluru Statement from the Heart (photograph via From the Heart)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): The Uluru Statement from the Heart (photograph via From the Heart)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Everything You Need to Know About the Uluru Statement from the Heart

- Book 1 Title: Everything You Need to Know About the Uluru Statement from the Heart

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $27.99 pb, 234 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Zdr4Dg

The elements of the Statement are popularly known as ‘Voice, Treaty, Truth’, which expresses a highly coherent proposal for reforming the law and recognising the rightful place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian political order. This was the democratic outcome of a series of regional dialogues designed by Megan Davis in her capacity as a member of the Referendum Council jointly appointed by the prime minister and the leader of the Opposition in 2015. These dialogues culminated in a National Constitutional Convention of more than 250 delegates, at which the Statement was adopted. Professor Davis, a Cobble Cobble woman and the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law and Pro Vice-Chancellor of the University of New South Wales, has now partnered with leading constitutional scholar George Williams, the Anthony Mason Professor and a Scientia Professor, and Deputy Vice-Chancellor, of the same university, to write this book. It contains an authoritative and concise explanation of the historical and contemporary processes which led to the Convention and commentary on the meaning of the Statement.

As Everything You Need to Know About the Uluru Statement from the Heart explains, the Statement must be understood in the context of the shameful history of exclusion of Indigenous peoples from the making of the Australian Constitution and their unrelenting and ongoing political struggle for recognition both before and since. The Constitutional Conventions at Sydney, Adelaide, and Melbourne in 1891 and 1897–98 from which they were excluded are to be contrasted with the National Constitutional Convention at Uluru in 2017 (and its antecedent processes), which was actually constituted by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates. Reflecting the central purpose of the book to inform all Australians about the Statement and how it was made, Davis and Williams describe this context and that struggle in a way that is highly accessible to the general reader.

What this campaign produced was a successful referendum in 1967 which approved a foundational constitutional amendment under which the Federal Parliament obtained legislative authority and therefore moral responsibility for the First Peoples of Australia. But, as Davis and Williams explain, it still left much unfinished business which those First Peoples took up. By the late 1990s, their efforts resulted in a general political consensus that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be ‘recognised’ in the Constitution. There has been no such consensus within either the First Peoples or the mainstream community as to how this recognition should be achieved. There are technical constitutional issues involved, which Davis and Williams discuss by reference to the various proposals that have been made. More importantly, however, is the issue of whether purely symbolic constitutional recognition is sufficient or whether substantive constitutional change is required, and if so of what kind. The unequivocal resolution in the Uluru Statement from the Heart is that the First Nations want substantive change in the form of a constitutionally protected Voice to the Federal Parliament, followed by a Makarrata Commission. The line of sight from the 1967 referendum to the position encapsulated in the 2017 Statement is illuminated in the book in a way that allows us to see the evolution of an important period of Australian history.

The Indigenous-led (Davis, Noel Pearson, and Pat Anderson AO) process by which the position encapsulated in the Statement was reached deserves careful study: it is the democratic mechanism by which different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples successfully came together to consider options and make collective decisions about matters of fundamental mutual concern. The Referendum Council rejected the usual ‘consultation’ model through which authority speaks to so-called stakeholders who are often left feeling disempowered. It built on traditional Indigenous decision-making processes and respected the unbreakable sovereignty of the First Nations. As expressed in the Statement, this sovereignty ‘has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown’. The Council adopted a ‘dialogue’ model through which it spoke with the delegates of First Nations and allowed them to exercise genuine and informed political agency. The thirteen dialogues considered the main options for achieving constitutional recognition, which led to the making of the Statement at the plenary Convention, as written by Davis and Pearson in an inspired all-nighter. In form and content, it is a beautiful message to the entire Australian community. The video of Professor Davis reading the Statement to this community in the presence of the delegates at the Convention is easily accessible on the internet and wonderful to behold. So is the visual form of the Statement signed by the delegates embedded in a dot-painting made by senior boss women of Uluru.

The First Peoples of Australia were excluded from the making of the Constitution because it was thought that they would soon disappear. In the mournful words of Daisy Bates, official policy then was to ‘smooth the pillow of a dying race’. As were all residual functions, authority over and responsibility for Aboriginal affairs were left to the states. Such is the resilience of the First Peoples that they have not disappeared. Supported by international human rights law, as expressed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which Australia has adopted, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are continuing their struggle for recognition and justice. In the words of Erica-Irene Daes, the Founding Chairperson and Special Rapporteur of the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations who oversaw the making of that Declaration, countries like Australia are now engaged in a process of ‘belated state-building’. Through her membership of the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Professor Davis is contributing to this process at the international level.

Belated state-building in Australia is not likely to end anytime soon. Everything You Need to Know About the Uluru Statement from the Heart deals with the unfortunate official political response to the Statement, which was to reject the demand for a Voice to Parliament protected in the Constitution. A process of ‘co-design’ for a non-constitutional Voice is now underway, which includes an extensive consultation. Time will tell whether the outcome is supported, but the vast majority of the thousands of submissions that have been made emphasise the fundamental importance of a constitutional underpinning. The final chapter of this book is a discussion by Davis and Williams about how this can be achieved at a referendum.

Comments powered by CComment