- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Years of wine and rage

- Article Subtitle: Much candour, less reflection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There’s a Judy Horacek cartoon in which a woman tells a friend that she once intended to be the perfect wife, a domestic goddess. When the friend asks, ‘So what happened?’, the woman replies, ‘They taught me to read.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

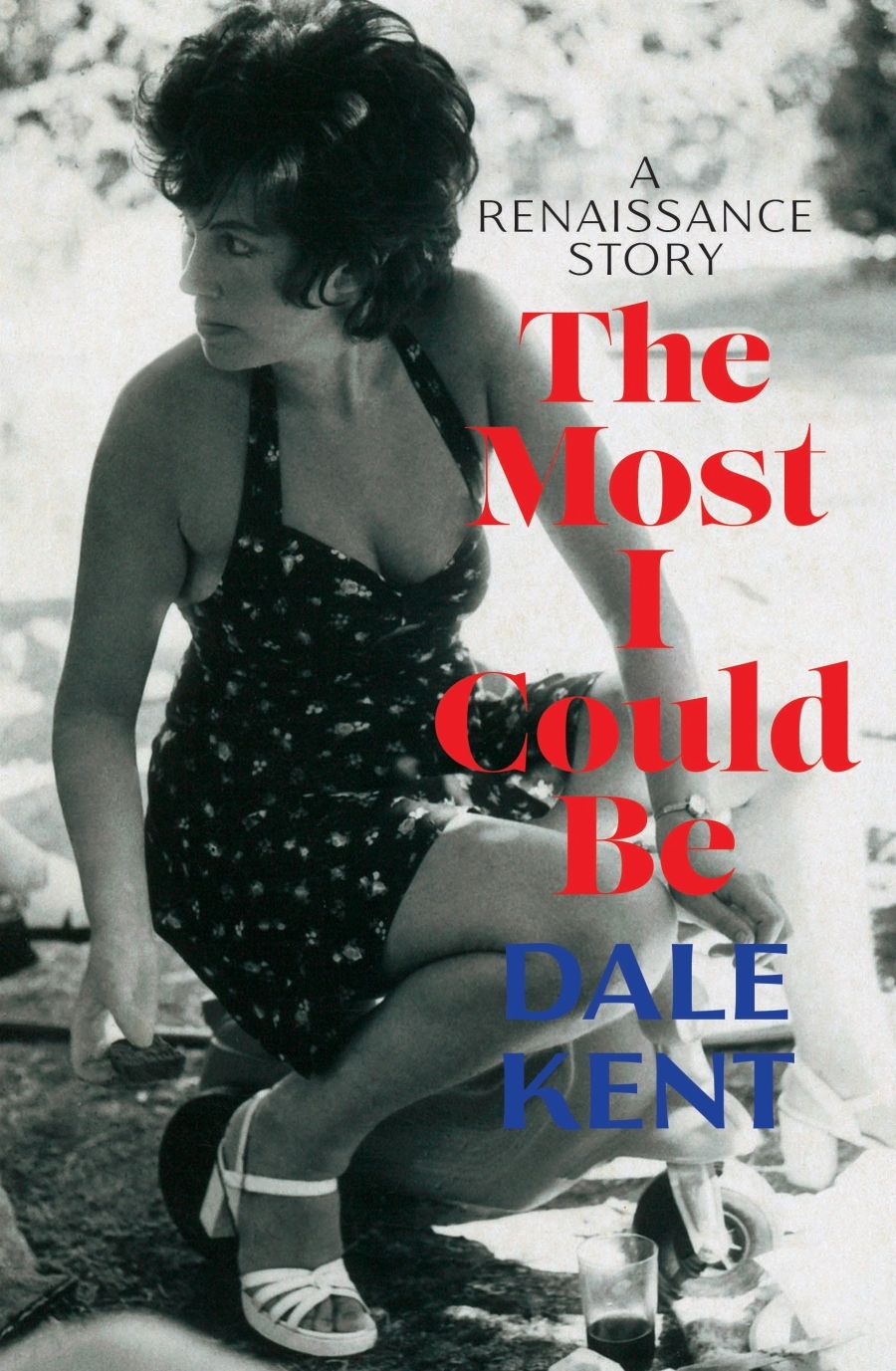

- Book 1 Title: The Most I Could Be

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Renaissance story

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.99 pb, 456 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/KeBgm9

Born in Melbourne in 1942 and incongruously named after Dale Evans (the sunny-natured and passive consort of cowboy star Roy Rogers), Kent was the daughter of a working-class family of Christian Scientists. She describes a joyless childhood with an abusive father and timorous mother. Her main solace was the world of Doris Day movies and MGM musicals; encouraged by her mother, she absorbed the lesson that the man of her dreams, her soulmate, would turn up. They would fall in love and live happily ever after.

Kent shone at school, had a stellar academic career, and eventually became a highly respected writer and teacher of the Italian Renaissance, especially the life of Cosimo de Medici. Her personal life seemed to be equally successful; at the University of Melbourne, she met another Renaissance scholar, Bill Kent, and they married. They travelled and worked together, and had a daughter.

It’s a story known to many women of Kent’s generation, and later ones: bright young girl escapes difficult background and finds salvation by means of education. If Kent’s autobiography were simply this, it would be pleasant but unremarkable. What lifts The Most I Could Be out of the ruck is the scorching fury that drives Kent’s clear and lively prose. Her inchoate rage led her to abandon her husband and daughter, to pursue relationships with a long line of highly unsuitable men, and to embark on years of excessive drinking. The contrast between her obviously stimulating academic career and this often awesomely destructive personal behaviour – she once glassed the face of a beau – makes this into a page-turner, not least because you wonder what she’s going to do next.

‘Rage and pain at sexist disparagement had come to permeate my being,’ she writes. This sounds like the cue for long and dispiriting descriptions of putdowns, of opportunities lost because of her gender, the kind of list that has become depressingly familiar. But Kent gives surprisingly few examples of appalling sexism and its influence on her career. Her gifts as a scholar and teacher were widely recognised, she had colleagues who respected her and her work, and apparently she has had no trouble making and keeping friends. She describes herself as gregarious, curious and focused, and for a long time her marriage and home life were reasonably harmonious.

So what was the reason for Kent’s rage? Her parents, she says. She rails against their example, especially that of her mother, who brought her up to believe that finding perfect love and happiness was her birthright. That’s pretty much it, and it’s puzzling, especially for a woman apparently so rational and intellectually accomplished. Life has taught most women to keep this fantasy firmly in its place, visited by reading Georgette Heyer novels or watching Bridgerton. It’s not often you find someone who has acted out this fantasy, certainly not as floridly as Kent did. At one point she writes, bleakly: ‘Where love and sex were concerned, I am not sure that I ever grew up.’ It is difficult to disagree. I do wonder whether the thrill of danger, the need to escape domestic and academic routine, was a factor in Kent’s behaviour, though she does not say so.

But the passionate anger and frustration that give this book its energy, and that have obviously driven Kent for most of her life, are extreme versions of the fury that talented women have so often felt about the hand that fate has dealt them. Fuming silently, however, was certainly not what Kent did. She is honest about her need to put her own desires ahead of her husband and child, though never of her work. All she ever wanted, she says, was to have the kind of freedom that men have enjoyed for centuries. If other people were hurt in the process, too bad.

Kent’s unwillingness to let herself off the hook, except to blame her parents, can be bracing. After years of behaviour damaging to herself and others, she finally achieves some self-awareness, largely because she comes to realise the consequences of losing her daughter forever. At the end of the book, she seems to have reached a kind of equilibrium.

So much candour with so little reflection makes much of The Most I Could Be an exasperating read: Kent often seems wilfully obtuse, failing to understand her own motives, not to mention those of other people. It’s probably unnecessary to add that the book is not distinguished by a sense of humour. Besides, Kent writes comparatively little about her academic career. I wished she had described how she developed such a deep love of the Italian Renaissance. If she had given more sense of the scholarship to which she has devoted her life and what it has meant to her, this would have been a more rounded, nuanced, and sympathetic autobiography.

Comments powered by CComment